P.O. Box 1142: The Secrets of Fort Hunt

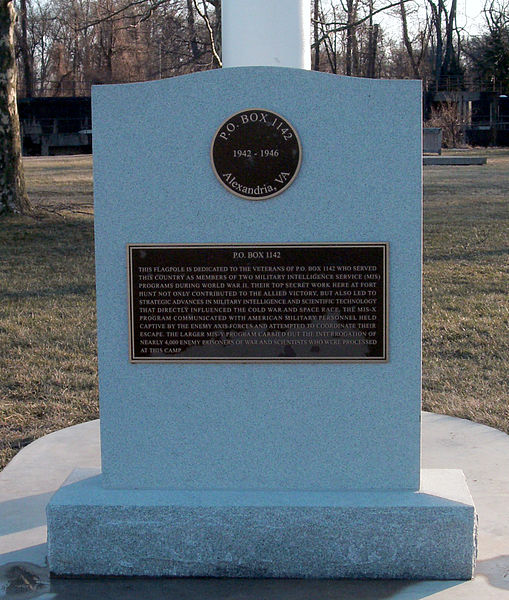

December 7th, 1941. Pearl Harbor smoldered following intense, coordinated attacks by air forces from the Empire of Japan. Within days, Americans were embroiled in the conflict that was the Second World War, while the American military scrambled to establish a competent intelligence gathering operation on the East Coast. Carved from a portion of George Washington’s Mount Vernon estate, Alexandria’s Fort Hunt began its life as a coastal fortification during the Spanish-American War. With its close proximity to Washington, Fort Hunt became an ideal location for one of the most secretive group of programs in American history. Codenamed after its post office box in Alexandria, 1142, Fort Hunt became a secret interrogation center for high value German POWs. The layers of secrecy did not stop there. Unbeknownst even to interrogators stationed there, Fort Hunt also held a program whose mission was to communicate and aid in the escape of Allied POWs trapped in several German camps throughout Europe.

Codenamed MIS-Y, the interrogation practices at Fort Hunt began in April of 1942. Interrogators were inspired by techniques witnessed in London. Prisoners thought to hold vital information were given lavish treatment, hoping that the contrast with harsh combat conditions might help loosen tongues. German prisoners would be brought into Fort Hunt for days or weeks of questioning before being “processed” and reported to neutral arbiters in Switzerland and to the Red Cross. Because of this, Fort Hunt was in violation of the Geneva Conventions of 1929, but its role as a “processing center” rather than a camp allowed intelligence officials to circumvent the rules to a certain degree.[1]

Despite these violations, prisoners at Fort Hunt spent their days or weeks there in relative comfort, sans the boredom of captivity. The food provided to prisoners was good and plentiful and interrogations were conducted in a relaxed and casual manner with tobacco and alcohol flowing freely. “You gained their confidence. Tell them the war was almost over and you guys are losing, so you might as well cooperate. Play chess with them. Take them shopping. Invariably they’d start talking,” states George Weidinger in an article for Cleveland.com. Interrogators used these techniques to coax details from their captives, without having to resort to torture. “We extracted information in a battle of the wits. I’m proud to say I never compromised my humanity,” said George Frenkel in an interview with The Washington Post.[2]

Prisoners were kept apart early on, but over time, interrogators began to realize that their most important finds came from informal, recorded conversations of mixed POWs. Soon, prison cells were bugged with recording equipment. Some highly perceptive prisoners discovered this, and kept Army clerks transcribing and translating meaningless chatter about topics as mundane as their favorite German foods to as crude as their sexual exploits. Yet despite their games, German prisoners were astonished with the amount of information that interrogators knew about their operations. Information gleaned from captured German U-boat crews were compiled by the Navy into booklets known as “Post Mortems” which were sent out to offices of Allied naval commanders to help combat the U-boat threat.[3]

German scientists were also guests of Fort Hunt in the later stages of the war. High value scientists such as Wernher von Braun spent time at Fort Hunt deciphering V-2 rocket technology that he designed for the Germans. Von Braun was part of a secret effort known as Operation Paperclip, an attempt by the U.S. to bring top German scientists stateside before the Soviet Union could get their hands on them. Von Braun would go on to be a key figure in U.S. space exploration. Another German scientist to spend time at Fort Hunt, Heinz Schlicke, developed infrared fuses which were later implemented in nuclear weapon technology.[4]

Several thousand German POWs and scientists passed through the walls of Fort Hunt between 1942 and 1945. No prisoners escaped, though one U-boat captain named Werner Henke, fearing he would be turned over to the British, was killed while attempting to escape in June of 1944.[5]

Besides interrogating German POWs, Fort Hunt also handled a top secret division to aid Allied POWs trapped in German camps in Europe. Codenamed MIS-X, many of the techniques used by this small group of individuals were inspired by similar programs being performed by MI-9, the British intelligence agency tasked with supplying British POWs behind enemy lines. Beginning in October of 1942, MIS-X officers helped trained servicemen in tactics for evading capture behind enemy lines, created escape and emergency kits (with money, maps, and other essentials) to be carried by all air crews, and trained specific individuals to use codes in letters going to and from POW camps in case they are captured, allowing MIS-X to stay in contact with POWs.[6]

While training servicemen while out of captivity is all well and good, one of the challenges MIS-X operatives faced revolved around getting aid and information to servicemen already in captivity behind enemy lines. Early on, humanitarian aid packages were targeted as optimal receptacles to smuggle items to POWs. That being said, MIS-X did not want to risk actual humanitarian aid being labeled as contraband and not being delivered to Allied troops who needed it. To work around this, MIS-X created false aid organizations such as the War Prisoner’s Benefit Foundation and Servicemen’s Relief to send humanitarian packages along with packages loaded with escape aids to POW camps in German territory.[7]

From a secret warehouse on the grounds of Fort Hunt known simply as “the Creamery,” intelligence engineers created items that today seem reminiscent of being in a James Bond movie. Articles such as shoe brushes and ping-pong paddles were hollowed out for storage of escape aids such as currency and cutting tools. Checker and chessboards were steamed to remove the top layer of the board so that items could be stored underneath. Playing cards were laced with pieces of maps that could be removed and reassembled into a full-size map for help in escape attempts. Makeshift radios were placed into the insides of cribbage boards—the cribbage pieces themselves were nails to provide contact points so that servicemen could receive broadcasts from the BBC. Baseballs were sent with aluminum cores which contained parts for radios as well. “My father loved Hogan’s Heroes. Especially when they were hiding radios in coffee pots and things like that. He used to say, ‘You know, that’s not too far off from what really happened,” said Peter Bedini in an interview with NPR, whose father worked in MIS-X. These parcels helped give American and other Allied POWs a fighting chance, allowing them to “fight the war behind barbed wire.”[8]

P.O. Box 1142 would operate through the entirety of the Second World War. Local residents would observe unmarked buses with darkened windows entering and exiting Fort Hunt on a daily basis, all the while never realizing the scope of activities occurring there. Six days after the war ended with the surrender of the Empire of Japan on August 14th, 1945, operatives at Fort Hunt received a terse, to-the-point command: “Burn all records.” With that, all documents and correspondence related to P.O. Box 1142 was burned. Leftover escape materials were also burned. P.O. Box 1142 was erased from history.[9]

Over the years, classified materials concerning the operations at Fort Hunt have slowly been declassified by the U.S. government. Even still, the records that remain are so cryptic that they are difficult to comb through.[10] It seemed that the crucial work conducted at Fort Hunt would be lost to history forever. Thankfully, National Park Service employees at Fort Hunt Park have been doing their very best to chronicle the events at Fort Hunt during the Second World War. Spurred by a park visitor, Brandon Bies, the park’s cultural resources specialist, began tracking down and interviewing veterans who were stationed at Fort Hunt. Park Service employees are now racing against the clock to interview and record these accounts while the veterans are still with us, so that their stories and the stories of Fort Hunt carry on for generations.[11]

Fort Hunt proves that history is about individuals—not events. The work that the individuals stationed at a secret military facility codenamed after its Alexandria post office box aided American forces in the Second World War and offers a lesson to today’s generation about how to conduct intelligence-gathering operations. Their work is a testament to their generation and we are so fortunate to learn of their history and give them the credit that they deserve while they are still with us.

Footnotes

- ^ John Hammond Moore, The Faustball Tunnel: German POWs in America and Their Great Escape (New York: Random House, 1978), pg. 30-33. Petula Dvorak, “Fort Hunt’s Quiet Men Break Silence on WWII,” The Washington Post, October 6th 2007. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2007/10/05/AR200710...

- ^ Moore, The Faustball Tunnel, pg. 33. “Long hidden, a Nazi-interrogation unit gets its due,” Cleveland.com, January 11th, 2008. http://blog.cleveland.com/metro/2008/01/in_1942_a_highly_classified.html, Dvorak, “Fort Hunt’s Quiet Men,” The Washington Post, October 6th, 2007.

- ^ Moore, pg. 38-44, 48.

- ^ Pam Fessler, “Former GIs Spill Secrets of WWII POW Camp,” NPR, August 27, 2008. http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=93649575.

- ^ Henke was part of a false propaganda campaign from the British who claimed that his U-boat, U-515, gunned down British survivors on the British ship Ceramic. See Timothy Mulligan, Lone Wolf: The Life and Death of U-boat Ace Werner Henke (Connecticut: Praeger, 1993).

- ^ Lloyd R. Shoemaker, The Escape Factory: The Story of MIS-X (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1990), pg. 11-21.

- ^ Shoemaker, pg. 29.

- ^ Shoemaker, pg. 16-21, 83-85. Pam Fessler, “Fort Hunt GIs Sent WWII POWs Care Packages,” NPR, August 19th, 2008, http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=93640350.

- ^ Shoemaker, pg. 199-206. Dvorak, “Fort Hunt’s Quiet Men."

- ^ Lloyd R. Shoemaker, an operative at MIS-X who had intimate knowledge of operations, conducted research from the declassified materials to write his book about the work of MIS-X. Even he admits that the remaining records are so disconnected as to “make little sense to anyone not having prior knowledge of the MIS-X operation.” See Shoemaker, pg. 207-217.

- ^ Pam Fessler, “Breaking the Silence of a Secret POW Camp,” NPR, August 18th, 2008. http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=93635950

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)