D.C.'s Half-Accidental National Mardi Gras

The modern-day DC Caribbean Carnival is a small affair, at least compared to the world-famous parades in carnival cities. There are plenty of revelers — and people celebrating Caribbean culture — but the capital certainly doesn’t come to a halt the way cities like New Orleans do on Mardi Gras. This hasn’t always been the case, however. For one year, in 1871, Washington, D.C. stumbled into hosting a Carnival parade that rivaled those in New Orleans itself. The National Fete, as it also became known, was an extremely patriotic version of the Carnival festivities, with national flags, “Yankee Doodle,” and rockets’ red glare mingling with the Lord of Misrule and the masquerade.

Carnival fetes and balls had been happening in Mobile, AL, since 1703, and some of the traditions of the Carnival were taking place around the American colonies even earlier than that; Philadelphia, for instance, held Carnival-like tournaments on occasion as far back as 1778.[1] By the 1870s, Carnival/Mardi Gras traditions were well established in several parts of the Deep South, but they had never yet ventured as far north as the nation’s capital.

The District’s carnival began as a celebration of “new wooden pavement on Pennsylvania Avenue,”[2] but it quickly snowballed into something entirely different and by far more enormous, absorbing both Washington’s birthday and Mardi Gras along the way to become a sort of nationalistic hybrid of revelry.[3] At the beginning, the newspapers only held vague hints of a masquerade. The festival organizers, however, had grander plans. Soon Mardi Gras traditions were thrown into the mix, notables from Baltimore and New York were invited to the scene, and every organization in town was invited to don costumes and march in a parade.[4] The knightly tournament, the masquerade, the balls — the committees added more and more in a seeming attempt to achieve maximum pomp with minimal circumstance for doing so.

The Carnival was set to occur on February 20 and 21, 1871 — Mardi Gras and the day before. By the time the week of the Fete rolled around, preparations were in full swing. Colored flags and flags of nations were hung from buildings around the street, and strings of lights were set up all along Pennsylvania Avenue. A goat race was planned, which over thirty goats were registered; one overeager young man brought his goat to registration, all the way up to the third-floor room of the Shepherd’s building.[5][6] Excitement in the District was high; the Evening Star, in particular, was looking forward to the carnival “brightening the dull routine of day to day life at the Metropolis.”[7]

Local businesses took advantage of the eager atmosphere, with many announcing carnival sales and stocking up on white shoes and black tailcoats;[8] many bars concocted “carnival cocktails” and “carnival punches.”[9] Private roadways announced they would give discounts to carnival-goers, as did the railroads into the town.[10] The city braced itself for the flood of people from all across the region who were expected to attend: 10,000 visitors were expected to pour in from out of town, so hotels were booked far in advance. Blocks of hotels were booked for specific purposes, including for the newspapermen from as far away as California and Oklahoma (then Indian Territory).

Regiments under Gen. William Sherman were summoned from New York to march in the upcoming parade. The committee even brought members from the renowned Mystic Krewe of Comus and the Cowbelian de Rakin Society up from New Orleans and Mobile, respectively, in order to really make it official.[3] Six thousand of their costumes were rented to D.C. citizens and guests; the German societies provided another four thousand.

On the days of the Fete, Pennsylvania Avenue thronged with spectators along benches that had been erected the day before. Events were constant throughout the day: foot, horse, and sack races took place past the Treasury Building; the “Velocipede Race” ended, improbably, with no one toppling over; more than two dozen goats raced down Pennsylvania Avenue. A drilling competition took place between volunteer regiments, some hailing from as far as New York, the prize being “a stand of colors” worth $1,000 ($19,600 today).[11] DMV rivalries were given the chance to be expressed with a “tournament” of knights on horseback. Ten knights each from Maryland, Virginia, and the District competed on the second day of the festivities, trying to hook a ring on their lances; D.C. residents will be pleased to know that G.P. Gwynn of the District, outfitted in argyle, won the day, as well as the right to crown the “Maid of Love and Beauty.”[12]

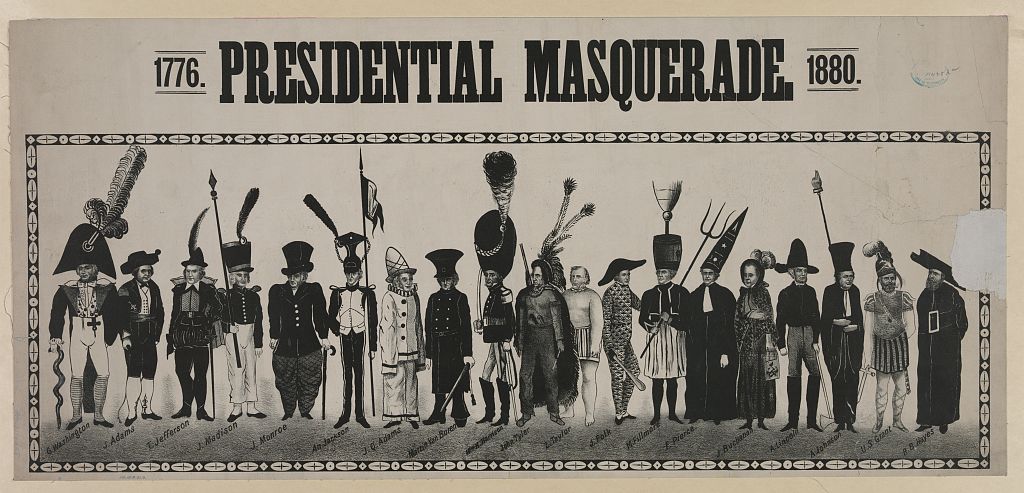

The crowning achievement of the festival, though, was the masquerade procession. Parading through the streets downtown, including Pennsylvania Avenue, thousands and thousands of costumed revelers mingled with figures of state. There were masquers in the parade poking fun at public and historical figures, including King Charles, William the Conqueror, and Joan of Arc; the Cabinet and the House and Senate marched alongside foreign dignitaries and contingents of the army and navy. Patriotic versions of Carnival traditions made their appearance, with floats in the parade such as the “Capitol on wheels,” and the “tableau” depicting “America - the land of the free.”[13] A large part of the parade was taken up by an elaborate procession poking fun at then-presidential candidate Victoria Woodhull, called “The Inauguration of the Female President.” The section included a musketed guard, a band, an elaborate set of cars with “Woodhull” and her Cabinet, followed by female voters with their disenfranchised husbands - all “composed of men dressed in female costume.”[14] Among the other participants in the parade were delegates from the various German Associations of the city, and a contingent of people in full Scottish dress, participating in caber tossing and the hammer throw.[15] With costumers dressed as fairies, Mother Goose characters, kings, and queens, the Evening Star rejoiced in “the fun of guessing” which public figure was under the mask.

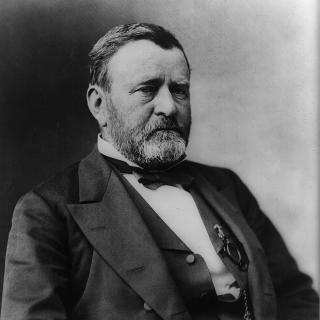

Some parts of the Carnival tradition survived intact, with the crowning of the Lord of Misrule, who led the masque parade, and the masquerade balls that followed the day’s festivities in the evenings.[16] There was a ball in the city for the opening of the then-brand-new Corcoran Gallery (in part to raise funds for the then-incomplete Washington Monument) and the gallery itself.[16] Much of the executive and legislative branches were present at a lavish ball at the Masonic Temple, including President Ulysses S. Grant and most of his cabinet.[17] The city was bursting with side events throughout the days and nights; the newspapers filled with reports of plays, pageants, street sideshows, and children’s choir and masquerade performances.[16]

After nightfall on both days, Pennsylvania Avenue was lit up with enormous electrical, gas, and calcium lights; strings of colored lights and lanterns added to the festive scene. Sixth Street’s triumphal arch and the street lights were lit with “open plumes of gas.”[18] The silhouette of the Capitol Building was the site of electric lights that flooded the surrounding area. Each evening was capped off by a huge fireworks display, which, improbable as it may seem, supposedly included a depiction of Washington on horseback.[19] All observers declared the event an enormous success.

Sadly, this tradition was short-lived. There is no evidence that D.C. ever again saw a Carnival on the scale of Mobile or New Orleans. Although there are references to Mardi Gras revelers in the next year’s Evening Star, and masquerade balls at various occasions remained in style, nothing compared to the Carnival frenzy of the year before.[20] By 1910, there was an article in the Washington Post explaining what the New Orleans Carnival was, suggesting that by this time, residents of DC were largely unfamiliar with Carnival customs — and so, memories of the capital’s Carnival receded into the distance.[21]

Footnotes

- ^ “Hints for the Carnival: Two Festivals of the Olden Time,” Evening Star, February 13, 1871, p. 1.

- ^ Note to readers: this took place in a time before the Internet.

- a, b “Letter from Washington,” The Sun [Baltimore, MD], February 6, 1871, p. 4.

- ^ Bizarrely, the invitation also seems to have been extended to some perpetrators of the Fenian raids. [“Board of Common Council, Evening Star, February 14, 1871, p. 4.]

- ^ Evening Star, February 9, 1871, p. 1.

- ^ It shows a lot about Washington, D.C. that half of the goats entered were named things like “Independence,” “Conqueror,” and “Rocky Mountain,” not to mention “Millard Fillmore.” [“Entrees for the Goat Race,” Evening Star, February 11, 1871, p. 4].

- ^ Evening Star, February 20, 1871, p. 1.

- ^ Evening Star, February 11, 1871, p. 2.

- ^ Evening Star, February 22, 1871, p. 1.

- ^ “Letters from Washington,” The Sun [Baltimore, MD], January 18, 1871, p. 4

- ^ The Sun [Baltimore, MD], January 30, 1871, p. 2.

- ^ Evening Star, February 21, 1871, p. 1.

- ^ Evening Star, February 18, 1871, p. 4. An individual also apparently fashioned a Capitol costume to wear, with legs sticking out.

- ^ Evening Star, February 18, 1871, p. 4.

- ^ “The Carnival - The Sons of Scotia to Participate - Scottish Comes to be a Feature,” Evening Star, January 31, 1871, p. 4. Members of the Scottish Associations came from across America to participate in the festivities.

- a, b, c Evening Star, February 21, 1871, p. 1.

- ^ Evening Star, February 10, 1871, p. 1. Apparently the Temple was a pretty common location to book for such events; the previous event held there, a week before, was the 21st anniversary of the Journeymen Bookbinders’ Society.

- ^ Safety regulations were much more lax in the 1870s.

- ^ Evening Star, February 21, 1871, p. 4. This was the largest of its kind in D.C. since the government had put a moratorium on Fourth of July fireworks some years prior, due to the Civil War.

- ^ Evening Star, March 1, 1872, p. 1.

- ^ Frederic J. Haskin, “The New Orleans Carnival,” Washington Post, February 7, 1910, p. 4.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)