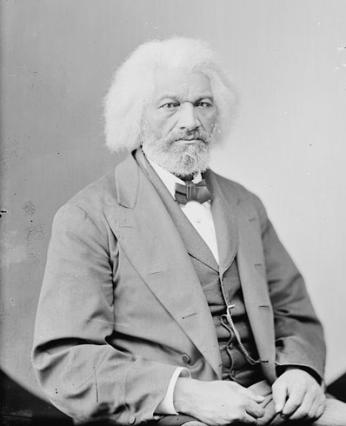

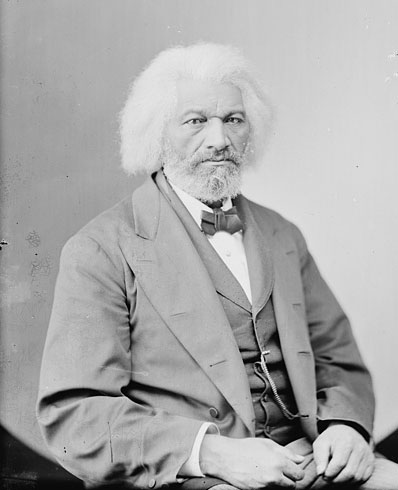

Frederick Douglass's Career in D.C. Government

Frederick Douglass spent time in Washington, D.C. during his career as an abolitionist, writer, and orator, but he was never a permanent resident. His presence prior to and during the Civil War was most notable as an advisor to President Abraham Lincoln during the debate over constitutional amendments to guarantee voting rights and civil liberties for African Americans.[1]

It wasn’t until his Rochester, N.Y. home was destroyed by fire in 1872 that Douglass took up permanent residence in the District. Relocating to Washington seemed a logical choice since he was already spending an increasing amount of time there. Three of his sons were already living in Washington, and he was quite busy running his newspaper, the New National Era. This weekly paper, founded in 1870, was dedicated to covering Reconstruction and African American life in Washington.[2]

Douglass’s career as an activist, writer, and newspaper publisher put him in close proximity to the world of politics. After the war, he was encouraged to move to the South and get himself elected to Congress, but he turned down the idea.

“The thought of going to live among a people in order to gain their votes and acquire official honors was repugnant to my self-respect,” Douglass wrote in his third autobiography, The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass, in 1881. “I had small faith in my aptitude as a politician, and could not hope to cope with rival aspirants.”[3]

This did not end Douglass’s involvement in politics. He actively supported the election of Ulysses S. Grant in 1868 in hopes that Grant would correct the failures of Reconstruction in the South that were leading to the disenfranchisement of African Americans and the rise of institutionalized racist policies.

On February 21, 1871, Grant signed the District of Columbia Organic Act, a law that established a new territorial government for the whole District of Columbia. Before this point, the cities of Washington and Georgetown were governed by separate territorial governments with the remainder of the federal territory in the District under the control of a court appointed by the president.

In April, Grant appointed Douglass to be part of the city’s eleven-member legislative council. At this time, he was still traveling between Washington and his home in upstate New York as well as running his newspaper. The demands on Douglass’s time proved too much, and he ultimately resigned his post on the city council on June 20. His son Lewis filled his seat for the remainder of his appointed term.[4]

In 1872, Douglass was nominated as a vice presidential candidate on the Equal Rights Party ticket, in part as a reward for his work in universal suffrage. He did not seek the nomination nor campaign for the ticket, choosing instead to be an elector for the state of New York in support of Grant’s reelection.

Douglass was elected president of the Freedman’s Savings and Trust Company in 1874. The bank was established in 1865 in the hopes of helping African Americans establish credit and build savings, but it quickly ran into trouble due to speculative investments and graft. By the time Douglass took over, the venture was beyond salvation. Despite his pleading to Congress for financial support and the investment of tens of thousands of dollars of Douglass’s own money, the Freedman’s Savings and Trust went insolvent later that year.[5]

In 1877, President Rutherford B. Hayes appointed him to the position of U.S. Marshal for the District of Columbia. He was the first African American to be confirmed for a presidential appointment by the U.S. Senate, and he held the post for four years.

The position was one of high controversy. Many District residents were against a black man being appointed to a post of high legal authority. Washington was a hotbed of racial tension during this period, and there was a feeling among some whites that Douglass would use his position to stir rebellion.

Many blacks were also against Douglass accepting the post because he was denied a traditional role of a U.S. Marshal for the District — formally introducing visiting dignitaries to the White House.

Douglass faced down the widespread condemnation and ridicule he received for accepting and holding his post. He made note that he had been a public guest of President Hayes on numerous occasions, and neither his race nor his inability to attend the White House in his formal role were grounds for his resignation. “I can say of my experience in the office of United States Marshal of the District of Columbia that it was every way agreeable,” Douglass wrote.[6]

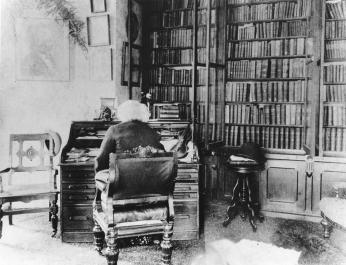

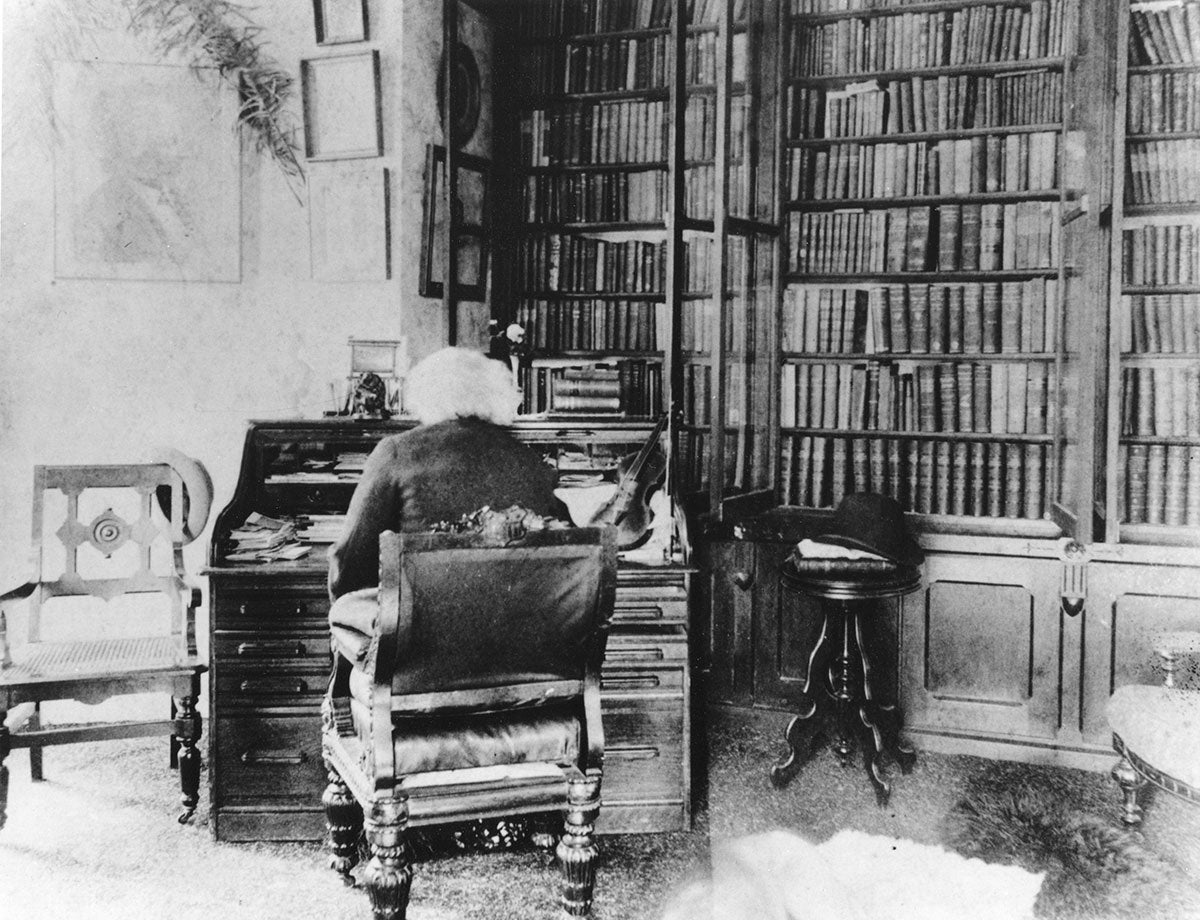

Frederick Douglass lived out his remaining years in Washington, D.C., and he continued his activities in politics and government up until his death in his home in Anacostia on February 20, 1895. His writings and his work for civil rights cemented his legacy as not only a distinguished citizen of Washington, but of the nation.

Footnotes

- ^ There has been much speculation about Douglass’s view of Lincoln’s dedication toward emancipation, but despite their differences, Douglass referred to Lincoln as “the greatest statesman that ever presided over the destinies of this Republic.” Mr. Lincoln and Freedom, The Lincoln Institute. http://www.mrlincolnandfreedom.org/inside.asp?ID=69&subjectID=4

- ^ View digitized versions of the New National Era at the Library of Congress site, Chronicling America: http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84026753/

- ^ Quoted in “The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass.” De Wolfe & Fiske, Co., Boston, 1881, p. 484. Digital version courtesy University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, 2001: http://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/dougl92/dougl92.html#p484

- ^ See John Muller, “The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass in Anacostia (Washington, D.C.) as told in the Washington Evening Star,” The Readex Report, Volume 9, Issue 1 http://www.readex.com/readex-report/life-and-times-frederick-douglass-a…

- ^ See “Freedman’s Savings and Trust Company” at BlackPast.org for more information: http://www.blackpast.org/aah/freedmen-s-savings-and-trust-company-1865-…

- ^ Quoted in “The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass,” p. 520. http://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/dougl92/dougl92.html#p520

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)