First Statue Representing D.C. Unveiled in U.S. Capitol

It was a long wait for sculptors and local politicians.

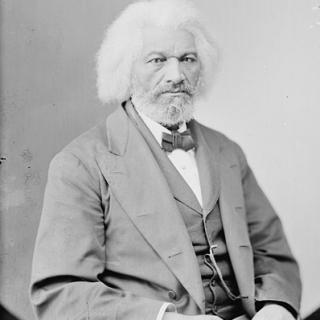

Since 2008, a seven-foot tall, 1,700 pound bronze statue of abolitionist Frederick Douglass stood in the lobby of a building called One Judiciary Square. It remained there for five years while Washington officials fought to move it to another building less than a mile down the road: the U.S. Capitol.

Today marks the one-year anniversary of the unveiling of Douglass’ statue in the Capitol Visitor Center’s Emancipation Hall. The ceremony was the culmination of a fight spanning over a decade.

Before the Douglass statue, there had never been a statue representing the district inside the Capitol — and Del. Eleanor Holmes Norton had been fighting to change that for years. In 2002, she introduced a bill in Congress that would permit the district to select two statues to place in the Capitol’s Statuary Hall.

Why Statuary Hall? The semicircular, two-story room, which served as the meeting space for the House of Representatives until 1857, now has only one purpose: to display two statues representing each state. That’s been the case since 1864, when Congress passed this piece of legislation:

“The President is hereby authorized to invite each and all the States to provide and furnish statues, in marble or bronze, not exceeding two in number for each State, of deceased persons who have been citizens thereof, and illustrious for their historic renown or for distinguished civic or military services.”

The collection grew, and eventually it spilled over into nearby rooms. Eisenhower is in the Rotunda. John Winthrop is in the Hall of Columns. And eventually, scattered among various chambers of the Capitol, there were statues of citizens from all 50 states — but none from D.C.

Because D.C. isn’t a state, the 1864 legislation effectively made it illegal to place a statue representing the district inside the Capitol.

Norton’s 2002 bill didn’t go anywhere, but a few years later, the district paid $200,000 for two statues — one of Douglass, and one of Pierre L’Enfant — hoping that they would eventually move to Statuary Hall. In the meantime, both statues were placed in One Judiciary Square, a government office building.

“The District routinely gets shafted on stuff like this,” Washington Post columnist John Kelly wrote. “Commemorative quarter? It took an act of Congress for Washington to get one. For the longest time, there wasn't even a D.C. flag in front of Union Station. All of this might seem minor compared with the egregious lack of congressional representation that the District's residents suffer. But symbols matter, especially in a city full of them.”

When Kelly tried to photograph the statues in their temporary location, he was stopped by a security guard.

“That’s not a tourist attraction,” the guard told him.

“Maybe it isn’t now,” Kelly wrote when he reflected on the encounter in his column. “The question is: When will it be?”

The bill made it to a House committee in the summer of 2010. Rep. Dan Lungren (Calif.), opposed it, and argued that the bill “tries to show that there is an equality between the District of Columbia and the other states.” It cleared the committee, but then House Republicans started attaching language to the bill that would weaken D.C. gun laws, and the bill stalled.

Lungren offered a compromise in 2012: D.C. could place one statue in the Capitol, instead of two. Douglass would represent the district, but L’Enfant would stay at One Judiciary Square. The bill passed the House in September, and it passed the Senate a few days later.

“D.C. residents pay more than their share of federal taxes, and are entitled to have two statues in the Capitol, like every state,” Norton said. “Our other statue, of Pierre L’Enfant, the man who planned the city of Washington itself, remains on display at One Judiciary Square, and I will continue to fight to bring that statue into the Capitol, as well.”

Finally, 11 years after Norton first introduced the bill — and 149 years after Congress began the Statuary Hall collection — Douglass’ statue was unveiled at a ceremony in the Capitol Visitor’s Center Emancipation Hall last year. The audience included national and local politicians, some of Douglass’ descendants, local students, and a number of museum employees.

“We know that a single statue is not enough,” House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi said at the ceremony. “It is incumbent on all of us to right this wrong of history and afford the District of Columbia the voice it deserves.”

Democrats onstage with Pelosi applauded at this remark, while House Speaker John Boehner and Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell remained silent. Both Republican leaders praised Douglass at the event (Boehner called him “an example for humanity that is unmatched,” while McConnell said he was a “leader of the Republican Party”), but neither mentioned the controversy.

Norton, on the other hand, spoke extensively about equal rights for Washington residents.

“Some may know of my strongly held views that D.C. residents must enjoy equal Congressional, voting and self-government rights with other Americans,” she said. “I must defer, however, to Mr. Douglass, whose fervor on this issue is unmatched by any I know or have heard on the subject.”

Douglass, who famously spent years advocating equal rights for black Americans, also spent time advocating equal rights for Washington residents. At the ceremony, Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid quoted Douglass’ autobiography:

“[Washington is] the one spot where there is no government for the people, of the people and by the people,” Douglass wrote. “Its citizens submit to rulers whom they have no choice in selecting. They obey laws which they had no voice in making.”

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)