No "Monopoly" on Monopoly: The Real Life History of One of America's Favorite Board Games

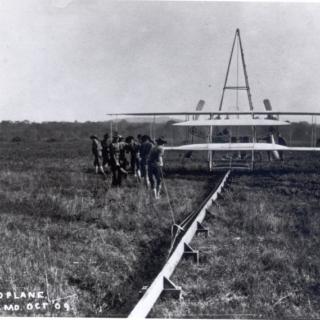

The official history of Monopoly states that the game was invented in 1935 by Charles Darrow, a man down on his luck during the Great Depression, who was catapulted to fame and fortune through his invention of a simple board game. The game was hugely popular, selling two million copies in its first two years in print. However, the game would have already seemed very familiar to intellectuals, leftists, and Quakers across the Northeast. And for good reason: the Monopoly we know today is a near-carbon copy of an earlier game, The Landlord’s Game, designed by a Prince Georges County Maryland stenographer named Elizabeth Magie — except that while Monopoly’s goal is to bankrupt your opponents, The Landlord’s Game was intended to show players the evils of monopolies.

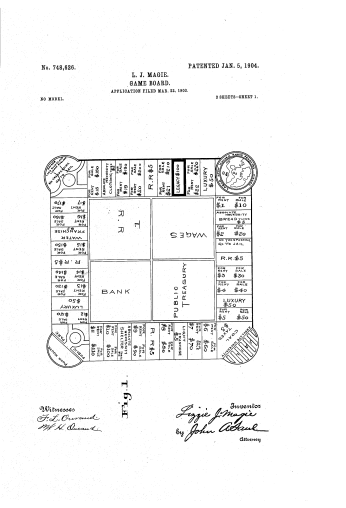

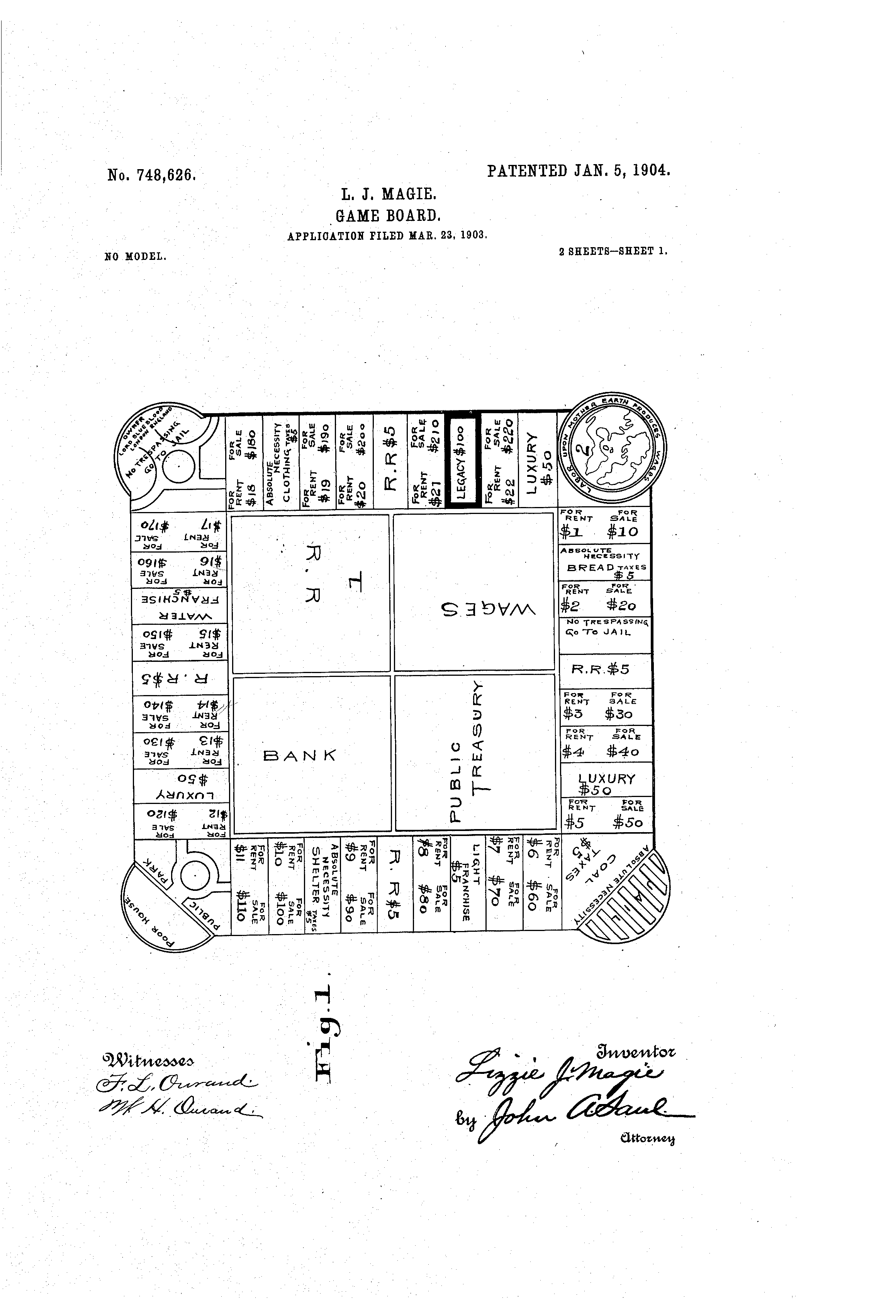

Elizabeth Magie received a patent for The Landlord’s Game in 1904, and its description of the game’s rules will ring a lot of bells for anyone who has played Monopoly. In Magie’s game, players move around the board buying properties and paying rent on their opponents’ spaces, trying to accumulate more money than their opponents. Perhaps most damningly, the gameboard features several spaces that have carried over unchanged into Monopoly, including the railroads placed at the center of each side, and the space marked “Go to Jail,” sending a player’s token to be imprisoned on the opposite corner (which, by the way, you had to pay $50 or roll doubles to escape). There are some minor differences between The Landlord’s Game and our familiar Monopoly, most notably that in Magie’s version, the game was over after everyone had gone around the board five times, saving everyone involved a lot of time and trouble.[1] But while the rules are almost identical, the ideals behind the two games were very different. Magie’s game, she hoped, would show players that scrambling for properties and charging each other exorbitant rents caused more harm to the community than good. As she said in her patent:

“The object of the game is not only to afford amusement to the players, but to illustrate to them how under the present or prevailing system of land tenure, the landlord has an advantage over other enterprises and single tax would discourage land speculation.”[2]

This was very intentional on Magie’s part; she wasn’t just “some housewife” who had come up with a board game on a lark. An outspoken feminist and progressive, most of her public statements and creations had a political purpose. The short stories she published had heavy undertones concerning the evils of competitive capitalism.[3] She even took out an ad in several national newspapers advertising herself as a “White Female Slave” for the highest bidder, in order to call attention to the state of gender inequality at the time.[4] But her one pet cause was the single-tax policies championed by Henry George, the progressive economist. George might not be a household name today, but he certainly was in the late 19th century; people claimed his Progress and Poverty had outsold every book but the Bible, and he was popular enough that he made a sizable showing in the New York City mayoral election.[5] (He lost, but he handily beat an unknown Republican named Theodore Roosevelt.) George's idea that all taxes but the property tax should be abolished, on the principle that this would lead to the elimination of poverty, as only the wealthy would be taxed, made him very popular with leftists and the lower classes.

Washington, D.C. had a community of single-tax activists, and Magie was one of the most active activists. She was the secretary of the Woman’s Single Tax Club of Washington, and counted among her friends Henry George, Jr., the son of her economic idol.[6] Magie very intentionally designed The Landlord’s Game so that it would exemplify Georgian principles; the game would drive home the idea that every player was better off when the community, rather than individuals, profited from property.[7]

The Landlord’s Game was a hit among activists and intellectuals, but not the general public. Still, these groups began to spread the game throughout the Northeast. Upton Sinclair was among the early players of the game, as he and Magie had corresponded in the past. Other early adopters of the game were Scott Nearing, Rexford Tugwell, and George Mitchell, who, fittingly enough for his trust-busting ethos, played a version without money.[8] All of these notables introduced it to their circles, where it quickly caught on.

The game’s popularity extended steadily into the 1920s (among those who had a propensity for economic theory-based board games, that is). People started calling it “the monopoly game” or “monopoly,” since that was the basis of the gameplay.[9] The game was often played on homemade boards, with rules transmitted by word of mouth, so players were rarely aware that Magie had invented it, or that anyone could claim ownership of it. People added their own house rules that, in turn, were passed around as part of the game. People began to name the spaces after streets in their own cities, and in Atlantic City, the “monopoly game”-loving Quaker community added hotels to the game. Although Magie filed a patent for an updated version in 1924, the game had already passed beyond her control, and most people assumed it was in the public domain. By this time, the game already resembled the modern-day Monopoly more than the original Landlord’s Game.

The game continued in this oral-tradition way until Charles Darrow, an unemployed man in dire financial straits, first learned it at the household of a Quaker acquaintance in 1933. Darrow requested a written copy of the rules, and soon produced his own copy, enlisting a friend to draw the now-iconic illustrations on the spaces.[10] Darrow shopped “his” game around to several game companies, and in March 1935 Parker Bros. purchased Monopoly for an initial payment of $7,000. The game was a smash success — over two million copies were sold in its first two years on the market.[11] Parker Bros were hoping to patent the game, but the company was worried about possible claims of patent infringement; even they saw the close similarities between Monopoly and The Landlord’s Game.[12]They knew they had to take preventative action.

In November 1935, George Parker of Parker Bros. visited Magie in her Arlington, Virginia[13] home to purchase her patent for The Landlord’s Game. Parker told her that he was interested in distributing her game and would buy it and two others from her to be mass-produced by his company. Magie accepted and received a one-time payment of just $500 in exchange for the patent. She was delighted that her economic beliefs would soon have a wider audience; she sent Parker a letter — heartbreaking in retrospect — bidding “Farewell to my beloved brain-child,” and urging her game to “not swerve from [its] high purpose and ultimate mission.”[14]

One month later, Charles Darrow submitted his patent for Monopoly. The Parker Bros. version of the game continued to be wildly successful, with two million copies sold between 1935 and 1936. Much was made of the rags-to-riches story of Darrow’s invention, which was (and still is) printed in every copy of the game’s rules.[15] Parker Bros. released The Landlord’s Game in 1939, with a newly designed board that obscured its connection to Monopoly. It and Magie’s two follow-ups flopped, none of the three even coming close to Monopoly’s popularity.[16] Magie felt betrayed, but her brainchild continued to spread across America, as far beyond her control as ever, devoid of her initial message.

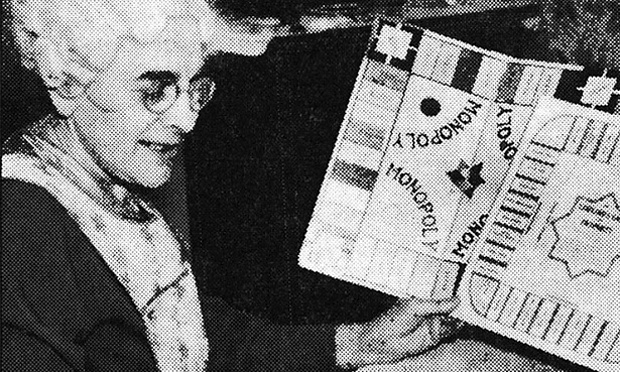

Magie continued to invent games to exemplify political principles, including one to prove that World War II was caused by “tariff barriers.”[17] None of them got anywhere close to the attention that Monopoly did. In 1936, Magie finally got her chance to speak out, protesting to the Washington Post and the Evening Star that she had been the true inventor of Monopoly, not Darrow. However, these articles were far from scathing indictments of plagiarism. The Post refers to Magie as “the inventor of Monopoly,” but goes on to refer to Darrow “improving” the game that he came across, implying that he still deserved credit as Monopoly’s architect.[18] The controversy died away, not to resurface for decades after Magie’s death in 1948.

Today, Monopoly has been translated into forty-six languages and is played in 114 different countries. Hasbro, the game’s current owners, estimate over 250 million copies have been sold. Charles Darrow died a millionaire, acclaimed as the inventor of the world’s most beloved board game;[19] at the end of her life, Magie was still a typist, never having found widespread success with her writing or her games. Magie never made more than that initial $500 off either Monopoly or The Landlord’s Game. Tragically for Magie, capitalism won out in the end, as it always does in modern-day Monopoly.

More Information

If you’re interested in learning more about Elizabeth Magie and the history of Monopoly’s transmission, a great place to start would be with Mary Pilon’s fantastic new book, The Monopolists: Obsession, Fury, and the Scandal Behind the World’s Favorite Board Game, which I have sourced heavily here.

Footnotes

- ^ U.S. Patent Office, Patent No. 748,626.

- ^ U.S. Patent Office, Patent No. 1509312.

- ^ Her writings made a moderate splash, too: she was published in Frank Leslie’s Popular Monthly and Godey’s, two well-known journals, and Upton Sinclair thanked her in the preface to his anthology The Cry for Justice.

- ^ Mary Pilon, The Monopolists: Obsession, Fury, and the Scandal Behind the World’s Favorite Board Game, (New York: Bloomsbury, 2015), 61-3. Magie did have a second goal, as well: to get funding for the next few board games she had been working on.

- ^ Mary Pilon, The Monopolists, 20.

- ^ Mary Pilon, The Monopolists, 26. Decades later, Marie would found and run the Henry George School of Social Science, which was held in her home. [Pilon, 137.]

- ^ This wasn’t even Magie’s first invention, by the way. At age 26, in 1893, she had engineered and patented a device that allowed paper to pass through typewriter rolls more easily. (The patent can be seen here.) [Pilon, The Monopolists, 28].

- ^ Pilon, The Monopolists, 72, 75.

- ^ Pilon, The Monopolists, 41.

- ^ In Mary Pilon’s book The Monopolists, one of her most remarkable achievements is in tracking down the specific person who gave the game to Darrow, and his original writing down of the rules and spaces, which is where the misspelling “Marvin Gardens” (rather than “Marven Gardens”) entered the Monopoly canon.

- ^ Pilon, The Monopolists, 107.

- ^ The company had more patent worries than just Elizabeth Magie. Daniel Layman had started selling the game Finance in 1931 - and making a hefty profit - four years after he had been introduced to the supposedly public-domain “monopoly game” through his college fraternity. Finance was nearly identical to the “monopoly game” that stemmed from Lizzie Magie’s The Landlord’s Game, and almost exactly the same as Darrow’s Monopoly. Like Monopoly, Finance even had the famous Atlantic City names of properties.

- ^ Magie (by then Elizabeth Magie Phillips, incidentally) had moved to Arlington sometime around 1924; shortly after inventing The Landlord’s Game, she had moved to Chicago, and lived there until her move to Virginia.

- ^ Pilon, The Monopolists, 121-3.

- ^ Although as of recently, Hasbro seems to no longer have the story of Darrow’s “invention” on their website.

- ^ Darrow attempted a follow-up to Monopoly as well, called Bulls and Bears. Never heard of it? There’s a reason: it was a huge failure, and Parker Bros. stopped manufacturing it after just a few years.

- ^ Jean Brownell, “Mrs. Phillips Invents Game to Show Tariff Barriers Caused the War,” Washington Post, October 25, 1940, p. 15. [By this time, Elizabeth had married, and went by her husband’s last name.]

- ^ “And Now It’s The Pastime of America’s ‘Rugged Individualists,’” Washington Post, January 28, 1936, p. 13.

- ^ “Man Who Gave Us ‘Monopoly’ Dies at 78,” Chicago Tribune, August 29, 1967.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)