When Owls Guarded the Smithsonian

In the 1960s and '70s, renovations in the Smithsonian Institution’s Castle sought to restore the building to its Victorian beginnings. Secretary of the Smithsonian S. Dillon Ripley, didn’t think architecture was quite enough to restore the #aesthetic. No, what the castle really needed was a few murderous, poopy barn owls.

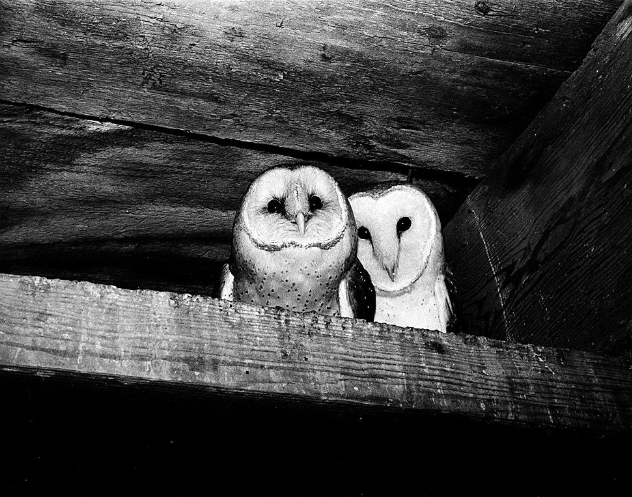

The Castle building had once before been home to owls, for at least a hundred years after its construction in 1855. Many of the Smithsonian workers who lived and worked in the building in the early years studied the birds including Spencer F. Baird, Secretary of the Smithsonian from 1878 to 1887. The owls were allowed to live problem-free in the tower until the 1950s, when Smithsonian workers became completely fed up with the birds and outed them as a menace. Their list of grievances was not insignificant. The accumulation of droppings over the years in the owls’ tower buckled the floor and the stench had started to spread to other areas of the castle. The owls also made a nuisance of themselves by frequently crashing into windows and swooping at the night guards. The complaints of the superstitious night guards fell on the deaf ears of Secretary of the Smithsonian and ornithologist Alexander Wetmore, who reportedly said “our guards must remain dauntless to any and all attacks.”[1]

The reins of the Smithsonian were taken up by Leonard Carmichael in 1953 and in the same decade the windows were finally closed against the owls, and they stopped returning to the tower. Wetmore was less than pleased about it, and blamed business interest: “the owls weren’t tidy and the business people couldn’t stand that.”[2]

Wetmore was probably happy to hear that the windows of the Castle were reopened to owls in 1967, after Ripley became Secretary in 1964. Luckily for the Castle workers, no owls actually showed up. It was up to Ripley to get owls in that Castle tower, and he went through a considerable amount of trouble to do so.

But why? Why work so hard to reintroduce what was previously deemed a menace? We weren’t joking about the #aesthetic. The reintroduction of the owls would add to the “spooky, romantic ambiance” of the Victorian towers.[3] Ripley was a hipster before it was cool.

He contacted the National Zoo in 1974 and received two owls to mate and raise. They were named Alex (for Wetmore) and Athena (for the Greek goddess) and some poor intern fed them dead lab rodents until the pair felt comfortable enough in their home for the windows to be opened wide and the owls to come and go as them pleased. Apparently, it pleased them to go and never come. By December 1975, the mates and their seven children had all flown the coop.

Ripley obtained a second pair and named them Increase and Diffusion, after language in the founding of the Smithsonian (“an establishment for the increase and diffusion of knowledge among men”).[4] Again a young member of the office was tasked with the perilous task of tending to them, as described in Amy Ballard’s Memoir:

Not only would I ascend career heights on a wooden ladder to the nest of owls, I would also have the privilege of wearing a jumpsuit that read ‘National Zoo Birds’ and a motorcycle helmet for protection against the owls in case they became alarmed and began to swoop down on me… The parents became extremely protective so it was necessary to wear the motorcycle helmet at all times. [5]

Other caretakers of the birds included the curator of the Castle and an assistant Secretary of State, who had a particular interest in owls and gladly saw to them on the weekends.

However, the whole thing was simply not meant to be and this second pair, with all their children, were gone by the end of 1977. Gratefully, the task was abandoned and the Smithsonian remains owl-free to this day.

Sources:

DesRochers, Alyssa. “Residents of a Different Feather.” Smithsonian Institution Archives. 2012.

Dillon, Wilton S. Smithsonian Stories: Chronicle of a Golden Age, 1964-1984. (Transaction Publishers, 2015).

Thomson, Peggy and Edwards Park. The Pilot & the Lion Cub: Odd Tales from the Smithsonian. (Smithsonian Institution Press, 1986).

“Smithsonian Drafts Owls to Occupy Castle Tower.” The Lewiston Daily Sun. 7 Feb. 1974.

Footnotes

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)