A Watergate Christmas Tree Lighting

Since the tradition began under Calvin Coolidge in 1923, the annual National Christmas Tree lighting has served to kickoff the holiday season in Washington and across the country—both as a celebration of the season and of America itself. As one of the lighting’s original organizers, Lucretia Walker Hardy of The Community Center Department, D.C. Public Schools, described it, “this Christmas tree will give the sentiment and the exercises a national character.”[1]

Over time, the ceremony grew from an evening of caroling and celebration to something much more important in the psyche of the American president and people. In times of war, it served as a platform for national reflection, and hopeful optimism for peace. At other points, it was used to highlight national advancements in technology.[2]

When planning for the 1973 Tree Lighting and Pageant of Peace got underway, all the familiar elements were there. The pageant would include a main tree and a collection of smaller trees representing each state and territory. In addition, there would be live reindeer, Santa Claus, a stage for performances, and a life-size nativity scene, just as there had been since the pageant’s inception.[3]

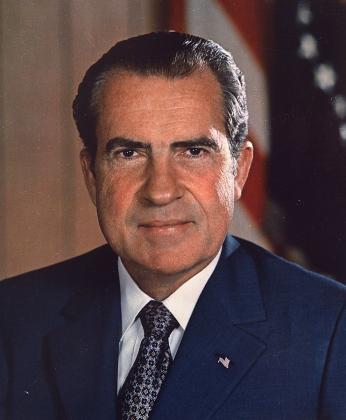

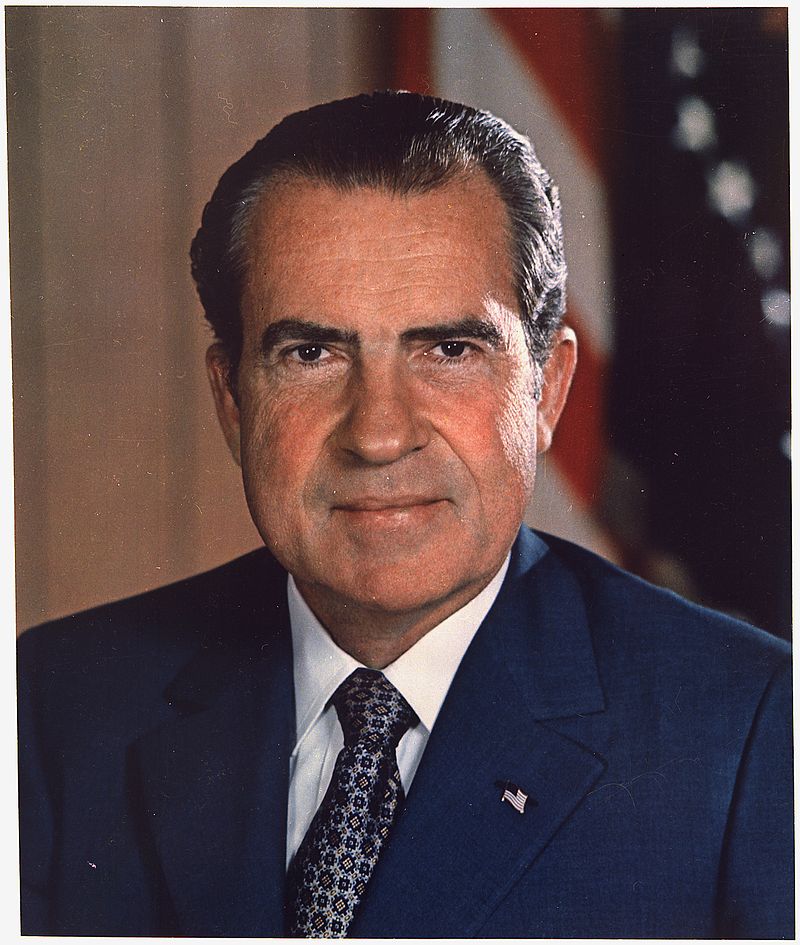

However, as the big day approached, domestic and foreign pressures were mounting upon the nation – and on President Richard Nixon himself. The geopolitical climate made for a unique — if also somewhat awkward — yuletide celebration.

Watergate, the energy crisis, and a recession had culminated in a perfect storm of national division. Just weeks before the Christmas tree lighting, in an attempt to deflect questions of professional impropriety in the wake of the Watergate scandal, Nixon famously declared “I am not a crook.”[4]

Across the country, however; support by the public and business sector for the President and his team was fleeting. His approval ratings were down 14 points since the previous January and accusations of corruption were growing – seemingly by the day.[5]

Outside the Oval Office, an increased environmental consciousness was present throughout the country as the OAPEC oil embargo forced Americans to reevaluate their use of energy in their daily lives.

Popular pressure prompted the National Park Service, to feature a living tree, rather than a cut tree, as the National Christmas Tree for the first time since 1953. Organizers ultimately settled upon a Colorado blue spruce, donated by the National Arborist Association, from Pennsylvania. Similarly, the smaller trees representing the states and territories in the Pageant of Peace were also living.[6]

The ongoing energy crisis caused more changes. Rather than stringing lights from top to bottom, organizers elected to illuminate the national tree with a single snowflake and shine a few floodlights from the ground. The new approach supposedly would reduce the celebration’s energy use by between 80 and 90%.

Lights weren’t the only thing missing from the ceremony; a U.S. Court of Appeals ruling banned the National Park Service from erecting a crèche within the pageant. A quick fix was to permit a newly formed, private group, the American Christian Heritage Society just outside the Pageant’s grounds to erect its own.[7]

Despite sagging popularity nationally, Nixon attempted to remain presidential as he addressed the crowd.

The President’s speech noted issues of the day, highlighting his accomplishments and legislative agenda, and called on the nation to strive for continued peace across the world and energy independence by 1980. The President did try to calm the nation’s nerves, calling the nation’s energy crisis “a problem of peace and not a problem of war.”[8]

Attempting to espouse a tenor of unity during the holiday season, amid a Senate investigation that had begun in May, the President noted the end of the draft and the return of American POWs, ultimately remarking, “…Christmas is not measured by the number of lights on a tree. The spirit of Christmas is measured by the love that each of us has in his heart for his family, for his friends, for his fellow Americans, and for people all over the world.”[9]

But Nixon’s earnestness was overshadowed by a rally of several thousand “cheerleaders with bullhorns” organized by staunch Nixon supporter Reverend Sun Myung Moon and his Unification Church. The enthusiastic demonstrators carried signs and banners with “God Loves America,” “God Loves Nixon,” and “Support the President” plastered across them.[10]

Moon’s rally, though apparently not officially sanctioned by the administration, seemed to have considerable pull with organizers that night. As Greenbelt resident Michael Ruddy witnessed: “Whether you had a ticket to the lighting or not, the only way you could get into the immediate area around the state was with a ‘God Loves the President’ banner. A young man who approached the gate at the same time as I did was rejected even though he had a ticket. I was admitted with only a ‘God Loves the President’ banner that I had found on the ground.”[11]

Afterward, the administration officially distanced itself from the Unification Church demonstration, with one spokesman saying the tree lighting, “was not the place for a political rally.” However, some questioned the sincerity of these statements.[12]

As Stephen Fitch, a George Washington University graduate student and a self-described Nixon supporter put it: “It was deplorable the manner which an event that has traditionally been a joyous occasion was turned into a propagandistic effort. ... An event such as the lighting of the National Christmas Tree belongs to the entire American people and should remain apolitical.”[13]

As it turned out, Nixon wouldn’t get the opportunity to lead another National Christmas Tree lighting while in office. Amid the Watergate scandal and an economic recession, he resigned his Presidency in August 1974.

Below is the full 1973 National Christmas Tree lighting ceremony, you can begin to hear raucous cheering in support of President Nixon around the 21:30 mark.

Footnotes

- ^ "The 1923 National Christmas Tree," National Park Service, June 10 2016, https://www.nps.gov/whho/learn/historyculture/1923-national-christmas-t…; “1941-1953 National Christmas Trees,” National Park Service, June 10, 2016, https://www.nps.gov/whho/learn/historyculture/1941-1953-national-christ….

- ^ “The 1923 National Christmas Tree;” "Roosevelt to Light Tree Christmas Eve," The Washington Post, Dec 07, 1938; "Tree Lighting to be Carried by Television," The Washington Post, Dec 21, 1947; Special to The New York Times "Coolidge Lights Up Tree To Inaugurate Nation’s Christmas," New York Times, Dec 25, 1925.

- ^ “1969-1973 National Christmas Trees,” National Park Service, June 10, 2016, https://www.nps.gov/whho/learn/historyculture/1969-1973-national-christ…; 1954-1960 National Christmas Trees,” National Park Service, June 10, 2016, https://www.nps.gov/whho/learn/historyculture/1954-1960-national-christ….

- ^ Carroll Kilpatrick, “Nixon Tells Editors, ‘I’m Not a Crook,’” The Washington Post, November 18, 1973.

- ^ "Watergate Cuts Nixon Popularity," Boston Globe, Apr 23, 1973; Terry Robards, "Watergate Causes Nixon to Lose Large Share of Business Support," New York Times, Aug 06, 1973.

- ^ The National Park Service expected the 40 year old spruce to live at least another 60 years, it was replaced in 1977. “1969-1973 National Christmas Trees;” Linda Newton Jones, "Living Christmas Tree due to Arrive Thursday," The Washington Post, Times Herald, Oct 10, 1973; "Sparing that Tree," The Washington Post, Times Herald (1959-1973), Aug 18, 1973; Majorie Hyer, "Pageant Differs from Christmas Past," The Washington Post, Times Herald, Dec 14, 1973.

- ^ “Nixon Lighting of Tree Will Turn on Snowflake,” Washington Star-News, Dec 13, 1973; Hyer, “Pageant;” Richard Nixon: "Remarks at the Lighting of the Nation's Christmas Tree," December 14, 1973, Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project, http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=4072.

- ^ Nixon, “Remarks.”

- ^ Nixon, “Remarks.”

- ^ Kohlmeier, “A Fitting;” Fitch, “Letter;” "President Lights New Tree, Notes Crisis-Dimmed Glow," Chicago Tribune, Dec 15, 1973; "Watergate Cuts Nixon Popularity," Boston Globe (1960-1984), Apr 23, 1973; Michael E. Ruddy, "Letter to the Editor 2 -- no Title," The Washington Post, Times Herald, Dec 22, 1973.

- ^ Ruddy, “Letter;” “President Lights;” Fitch, “Lights;”

- ^ “President Lights.”

- ^ Fitch, “Letter.”

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)