Douglas MacArthur's Olympic Tradition

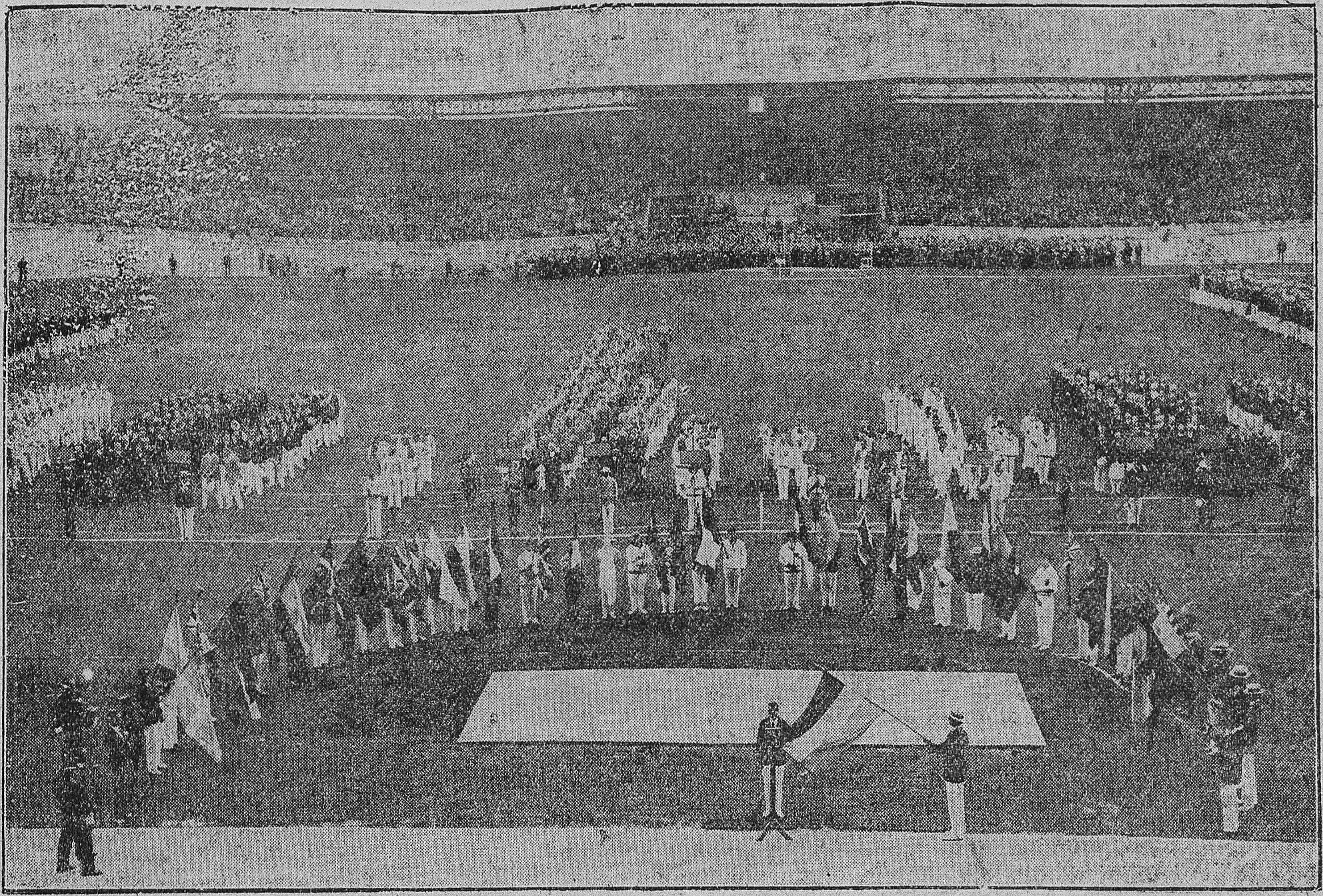

The Opening Ceremony is one of the highlights of the entire Olympic games. Greece enters first, followed by all participating countries in alphabetical order, with the host nation bringing up the rear.

Flag dipping, as the practice is known, is a customary part of the Opening Ceremony to show respect for the host nation. So why does the United States commit a "flag pas?"

The choice to not dip the flag has some murky origins. According to popular legend, it began in London at the 1908 games when Irish-American flag bearer Ralph Rose refused to dip the flag to Edward VII and claimed, “This flag dips for no earthly king.”[1]

This incident was used to support the Americans’ choice not to dip the flag to Adolf Hitler at the 1936 Berlin games. The American delegation also refused to give a “Nazi-like” Olympic salute and later claimed they were the only nation that did not lower themselves before the Nazis.[2]

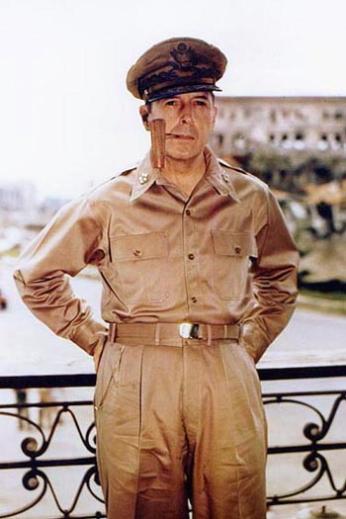

While Ralph Rose’s words are brimming with patriotism, they also seem to be the stuff of legend. The first decision to keep the American flag aloft came from a different patriot: Douglas MacArthur.

Before General MacArthur commanded the U.S. Army on the Eastern Front in World War II, he held a brief stint as the president of the American Olympic Committee, now known as the United States Olympic Committee.

After the sudden death of former president William C. Prout in 1927, MacArthur found himself with less than a year to prepare for the 1928 Summer Olympics in Amsterdam. However, he took to the task in military fashion.

Since 1919, MacArthur had been Superintendent of the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, during which time he revitalized the cadet morale through intramural sports.[3] MacArthur had a strong sense for both athletics and administration. Athletes recalled a mix of fear and admiration for the general.[4]

MacArthur approached the Olympics in the same manner he approached combat. It was, for all intents and purposes, a “war without weapons.”[5] After arriving in Amsterdam, MacArthur recalled giving an equally rousing speech to his "troops."

We represent the greatest nation in the world. We have not come so far just to lose gracefully, but rather to win, and win decisively. I rode them hard all along the line. Athletes are among the most temperamental of all persons, but I stormed and pleaded and cajoled. We have not come 3,000 miles just to lose gracefully.[6]

Before 1928, the United States had a mixed history of whether to dip its flag.[7] But for MacArthur, the choice was clear. When it came time for the United States to march in the processional, MacArthur ordered that the flag would not be dipped under any circumstances. He cited a military policy that “the National flag will not be dipped by way of salute or compliment,” not even to the president. Clarence ‘Bud’ Houser, a weight-thrower, followed orders and received “lukewarm” applause from the crowd.[8]

Back home, the decision not to dip the flag was met with criticism. “Is there not some military Emily Post in Washington who can quietly change the rules about flag dipping – without mentioning the fact to the American Legion?” asked an editorial in The Nation.[9]

Displays of national pride at the Olympics quickly escalated from ceremonial snubs to all-out brawls. The Washington Post made no mention of the flag dip but ran full coverage of the fisticuffs between a French secretary and Dutch gatekeeper after the gatekeeper prevented the French team from practicing in the Olympic Stadium. The French team threatened to withdraw without a prompt apology.[10] Two weeks later, the American boxing fans nearly rioted when Isaacs of South Africa was named the winner of a bout against American John L. Daley. Even MacArthur rose to his feet and called the decision unjust. [11]

Despite incidents of rather intense patriotism, the games were extremely successful for the Americans. Team USA took home a total of 56 medals, compared to Germany’s 31 and host nation Netherlands’ 19.

MacArthur declared the United States victorious, but apologized for not winning by a wider margin.[12] When the General arrived stateside, he wrote to President Calvin Coolidge in the style of submitting a military report. “Nothing,” he wrote, “has been more characteristic of the genius of the American people than is their genius for Athletics.”[13]

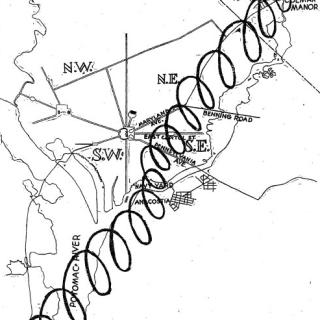

Having secured his win, MacArthur returned to military duty in Manila.

It fell to the AOC’s new president, Avery Brundage, to defend the lack of flag-dipping. He argued that the AOC received criticism when the flag was dipped as often as when it was left aloft, and suggested to the International Olympic Committee to create national banners to dip instead. The idea was rejected.[14]

The 1932 winter Olympics, held in Lake Placid became an immediate test of whether the United States would dip its flag to its own leaders. The flag-bearer indeed dipped, not to the president, but to then-New York governor Franklin Roosevelt. Sources differ as to whether the flag bearer for the 1932 summer games in Los Angeles also dipped.

However, in 1936 Berlin, there was no question on whether to dip. Bulgaria, Iceland, and India also protested the Nazi games with upright flags.[15]

The next Olympics were not held until 1948. By that time, General MacArthur’s upright flag was legally incorporated in the first sentences of the United States flag code: “No disrespect should be shown to the flag of the United States of America; the flag should not be dipped to any person or thing.”

Footnotes

- ^ Mark Dyreson, "‘This Flag Dips for No Earthly King’: The Mysterious Origins of an American Myth," The International Journal of the History of Sport 25, no. 2 (2008).

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ John A. Lucas, “USOC President Douglas MacArthur and His Olympic Moment, 1927-1928,” OLYMPIKA: The International Journal of Olympic Studies vol. 3 (1994).

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Dyreson, “This Flag Dips for No Earthly King.”

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Alan J. Gould, “Dutch Sooth French with Apology,” The Washington Post, July 29, 1928.

- ^ “Americans Stage Near-Riot At Olympic Fight Decision,” The Washington Post, August 11, 1928.

- ^ J. P. Abramson, “Olympic Marks Show General Athletic Gains: MacArthur's Report Notes Advance in Competitive Excellence Everywhere,” New York Herald Tribune, August 26, 1928.

- ^ Lucas, “USOC President Douglas MacArthur and His Olympic Moment.”

- ^ Dyreson, “This Flag Dips for No Earthly King.”

- ^ Patrick Cain, “Why Won’t Team USA Dip the Flag at the Opening Ceremonies?” Mental Floss, accessed August 4, 2016, http://mentalfloss.com/us/go/31317.

![Two soccer players run after ball in rain. [Reprinted with permission of the DC Public Library, Star Collection, © Washington Post]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2025-08/Washington%20Diplomats%20soccer%20game%20-%20DCPL_061_STARSUBJECT_1037_Soccer_Teams_Washington_Diplomats%20%28Star%207%20of%207%29.jpg?itok=Y2KVWCC6)

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)