1922: Washington's Deadliest Blizzard

Washington, D.C. has been battered by some brutal winter storms, but none has been more lethal than the blizzard that hit the District in late January 1922. Today, that two-day storm is still remembered as the Knickerbocker Blizzard. That's in grim recognition of 98 people who lost their lives and the 133 who were injured in the catastrophic roof collapse that it caused at Crandall's Knickerbocker Theater, once the District's biggest and grandest movie house.

The Knickerbocker, located at Columbia Road and 18th Street Northwest in Adams Morgan, was one of the jewels in the crown of local movie entrepreneur Harry M. Crandall, who himself was one of Washington's most stirring Horatio Alger stories. As a 1922 Washington Post profile detailed, Crandall was a fourth-grade dropout who'd started out his working life as a grocery clerk and telegram delivery boy, before investing his hard-earned savings of $20 on a partial payment for a team of livery horses. He did well in the cab business, but saw that the coming of the automobile would put him out of business. After going to a silent picture at the old Unique Theater on D Street one evening, it occurred to him that movies were "the coming thing." In 1907, he opened the Casino, a theater at Fourth and East Capitol streets, which seated just 80 patrons, and charged a nickel to a 10-minute-long silent film. It proved so profitable that he soon was able to sell it for $800, and began raising funds from investors to build a regional string of bigger, grander theaters that stretched over an expanse from Roanoke, Va., to Cumberland, Md. In the District, he owned the Metropolitan Theater on F Street, which had a spectacular 60-foot-tall vertical sign and stately Doric columns in front. That theater would become the first in the District to show local product Al Jolson's The Jazz Singer in 1927.

The Knickerbocker, built at around the same time as the Metropolitan, was even fancier. The palace of Indiana limestone and what a Post article cryptically described as "Pompeiian art brick" was designed by local architect Reginald W. Geare and erected at a then-lavish cost of $150,000, plus another $60,000 for the land. At its grand opening in 1917, a slew of silent-era stars, including Francis X. Bushman, were recruited to make personal appearances as Crandall showed the drama Betsy Ross, and a crowd filled the 1,700-seat theater.

But as lavish as the Knickerbocker was, its grandeur hid flaws in design and construction, and corners were cut to make up for a shortage of structural steel during World War I.

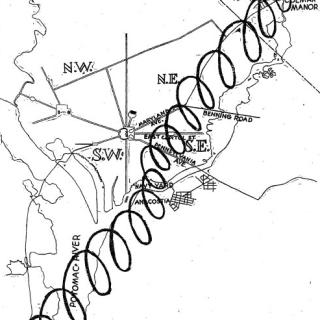

Those flaws were finally exposed by a massive winter storm that hit the U.S. east coast from South Carolina to Massachusetts on January 27, 1922. That afternoon, snow began to fall on the District and continued through the night. Eventually, it blanketed the city with 29 inches. Streetcar lines were paralyzed and there were a plethora of car crashes, according to the Post's coverage. But Washingtonians insisted on venturing out anyway, catching rides in taxicabs that braved the elements. One of the places they chose to go was the Knickerbocker, which on January 28 was showing Get-Rich-Quick Wallingford, a comedy starring Sam Hardy and Doris Kenyon.

At about 9 p.m., the evening's second showing was just getting underway, and the theater was filled. According to the Post's next-day account, a man who had just entered the theater heard the audience erupt in laughter. Then, suddenly, there was a different sound, a frightening roar. It was the roof of the theater, weighted down by snow, breaking loose from its steel moorings. In the candy shop in the lobby, a witness recalled feeling "a terrible gust of wind and smoke" that blew the theater's doors open. As the roof and ceiling came crashing down, they caused the theater balcony to collapse as well. "Most of the audience was entombed," the Post noted. Screams of people buried in the debris could be heard outside.

A man who apparently had been in the lobby managed to get out the front doors safely, and he immediately ran for medical assistance. The first responder on the scene was Dr. Joseph F. Elward, a physician who had been making a house call nearby. He later recalled that the first patient he treated was a man whose arm had been torn completely off his shoulder, though he was in such a state of shock that he didn't realize it was gone, and implored the doctor not to amputate it.

Before long, other doctors and police officers, arrived on the scene to help, as did a Catholic Priest, Father Carroll of St. Patrick's parish, who helped care for the injured and stood ready to offer last rites to those who were near death. They staged a frantic search and medical triage in the ruins of the theater, whose four walls were still standing, even as snowflakes continued to fall. But the damage to the theater was so great that the rescuers were unable to move the massive debris by hand. They and the trapped victims had to endure an agonizing wait until workers from the Fuller Construction Co. showed up with hydraulic jacks, acetylene torches, and equipment to clear the area. Strangely, as they labored, the theater's illuminated sign somehow continued to stay lit, advertising the movie as if nothing had happened.

But even then, it took hours to free the victims. One of them, a 15-year-old boy, was had almost but not quite made his way out of the theater, and was partially pinned under the roof at the entrance, with his upper torso free but his legs pinned. He must have been in excruciating pain, yet according to the Post account, he remained calm, and did not squirm or cry out in pain. His sheer bravery inspired the rescue workers, who realized that if they could somehow lift up the fallen roof, they might be able to save him and many others. Finally, using automobile jacks, they managed to raise the piece that was on top of him a tiny bit. Finally, "the boy smiled," according to the Post account. "He knew that eventually he and his fellow prisoners would be free." Unfortunately, the Post reporter didn't get the boy's name, and it isn't known whether he survived his injuries.

In the days that followed, public anger began to rise about the tragedy, especially after investigators interviewed witnesses who recalled theater employees had talked about whether to remove snow from the theater roof, but finally decided that it wasn't needed. A coroner's jury investigating the accident called architect Geare to testify about whether he had made errors in his design. Geare testified that he believed the collapse had been caused by a flaw in the structural steel. But John Howard Ford, whose firm, Union Iron Works, had fabricated the steel, blamed it on defective walls. After a week of testimony, the jurors decided that both men were criminally responsible, and indicted them for manslaughter, along with three others involved in the construction. But they got a reprieve from federal judge Frederick Lincoln Siddons, who decided that the indictments were too vague and dismissed them. But civil suits followed, and Geare's reputation never recovered from the disaster. In 1927, he committed suicide.

After the disaster, Crandall was urged by local businesspeople to rebuild the theater. He hired architect Thomas Lamb, who refashioned the remaining shell into the Ambassador, which opened in 1923. But Crandall, like Geare, had been forever scarred. A few years later, in 1927, he sold his theater chain. In 1937, he also took his life, leaving behind a note asking the "newspaper boys" not to be too hard on him. The former multimillionaire left behind an estate that consisted of a $500 diamond ring, a watch worth $50, a few pieces of furniture, his clothing, and some worthless stocks.

The Ambassador theater, the Knickerbocker's replacement, stayed in business for decades. But the in late 1960s, it had become what the Post called a "psychedelic theater," used by counterculture types for rock concerts. It was the location of Jimi Hendrix's first concert in Washington in August 1967, and several months later, hosted a reading by novelist Normal Mailer. Two years later, though, the owners decided to have it demolished, with the aim of redeveloping the site. Since the late 1970s, a bank has been located there.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)