Countess Marguerite Cassini: D.C.'s Diplomatic Social Butterfly

When Countess Marguerite Cassini first arrived in DC in 1898 during the McKinley administration, she accompanied the first Russian Ambassador to America, Count Arthur Cassini, as his 16-year-old “niece.” An air of mystery shrouded her origins, but as the oldest female relative of the ambassador, the “Countess” was the embassy’s official hostess. At state functions, she would be seated in the proper place for the Russian hostess — at the top right below the British, French, and German hostesses. The wives of the diplomatic corps bristled to be placed beneath an unmarried teenager, who was thought to be “neither a [countess] nor, according to rumor, a Cassini.”[1] To be fair, the Capital gossip wasn’t entirely wrong; young Marguerite wasn’t a countess, and the count was not her uncle. He was her father.

Yes, it’s true; Marguerite’s father was none other than Arthur Pavlovich Nicolas Cassini, Count de Cassini. And her mother? Stephanie van Betz, a famous singer from a family of theater people. Back in 1880, a woman of the theater could not just marry a count willy-nilly. Stephanie and Arthur were married secretly in London, and over the course of Marguerite’s life, Stephanie posed as a servant in their house. Marguerite was publically referred to as the count’s niece or adopted daughter, but was apparently suspicious enough to raise questions.

How did young Cassini overcome this to become the “algebraic x of diplomatic circles?”[2] The Washington Times records that the Count made a trip to Russia in the summer of 1899 and was able to persuade the Emperor to officially recognize Marguerite as Arthur’s daughter (the papers called this “adoption”) and officially declare her a countess.[3] With the weight of Russia behind her, the diplomatic corps was forced to accept Countess Cassini’s place near the head of the table. And after her father became dean of the corps, and Cassini became best friends with newly inaugurated first daughter Alice Roosevelt, she sat at the very head of the table.

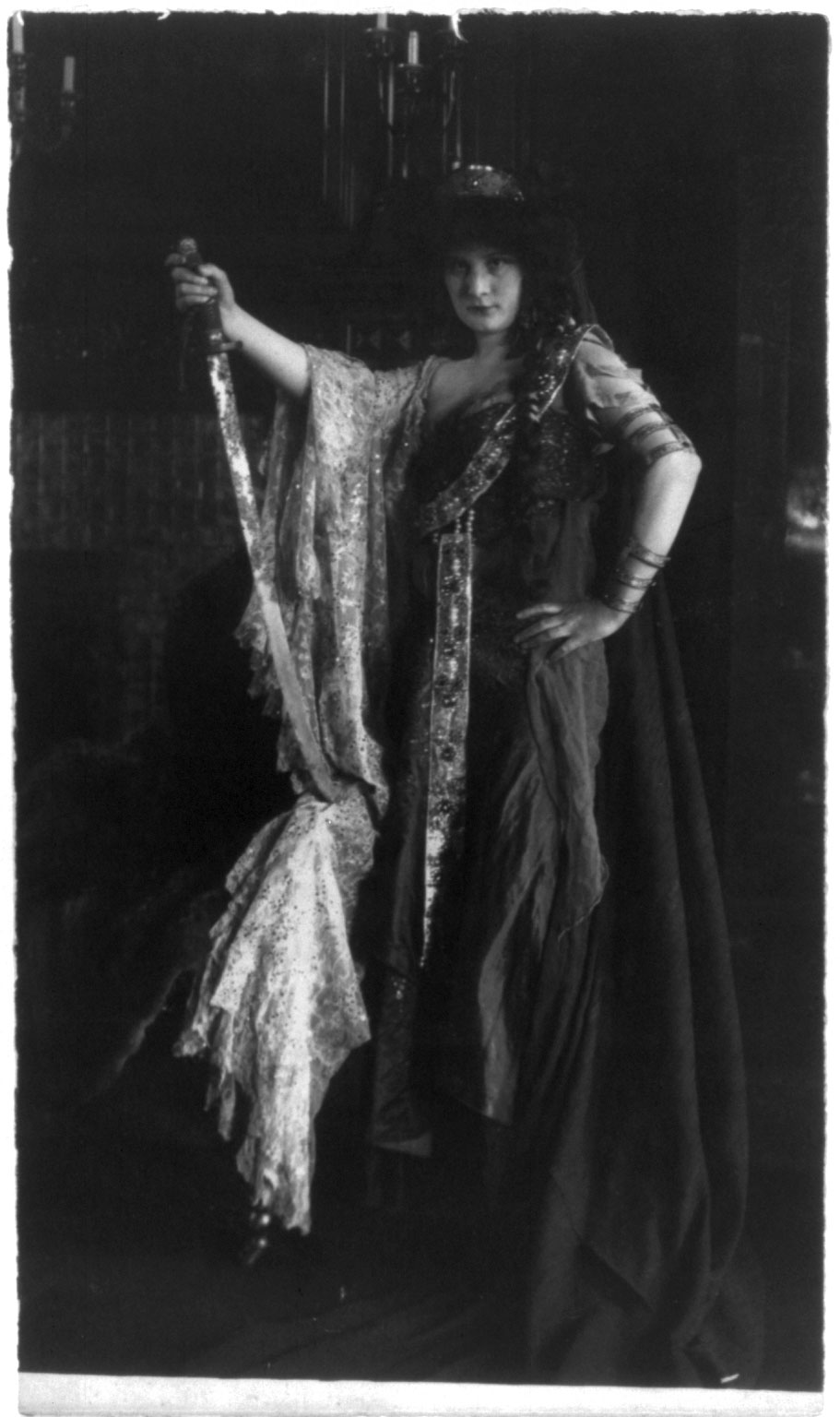

Marguerite and Alice’s friendship “had all the violence of a bomb,” and they treated DC as their own personal playground. They formed one of the “most powerful and autocratic” cliques since Grant’s presidency. The members of this young clique used their wealth and power to “thoughtlessly to impose their fads, their caprices, on everyone- a veritable reign of terror.”[4] Marguerite and Alice skipped out on $100,000 (over $2 million today) parties thrown in their honor, drove bright red convertibles, and even smoked in public, “the most abandoned act of all!”[5] While Alice was famous for her blue eyes, it was Marguerite’s wardrobe that turned heads. Even twenty years later, the papers were still talking about the time she spent $20,000 (over $400,000 today) on clothes in a single year.[6] But even with all the fuss about her skintight dresses and eccentric hats, no one argued that there was an iron-strong will beneath.

When learning that the Brodhead-Nell-Morton mansion at 1500 Rhode Island Avenue, NW, was vacant, Marguerite saw a prime chance to move her family into a much classier residence (although the old one was no joke). She marched directly to the property manager’s office and asked, very sweetly, to speak to the man in charge. When told that he was in bed with pneumonia and could not possibly see anyone, she bullied the doctor until she was let in. While no one else was ‘in the room where it happened,’ when Cassini left she had the house and she had it at a discount.

During the Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905), the Count asked his daughter to turn on the charm to get the newspapers to be more pro-Russia. Marguerite charmed one reporter so well he offered to leave his wife for her! She turned him down, but flirting with unavailable men was a particular game with her. When introduced to Nick Longworth (Ohio congressman, future Speaker of the House) at a party, the hostess warned Marguerite “be careful, he’s dangerous,” but also warned Nick “be careful, she’s very dangerous.” It was Marguerite’s dangerous quality that cooled her and Alice’s friendship. Nick Longworth, who would later propose to Alice, showed a bit too much interest in the countess and Alice suddenly found herself busy when Marguerite came to call.

Not that Marguerite didn’t find time for real romance. She worked out an elaborate scheme with her butler to receive letters from a gentleman acquaintance her father didn’t approve of: when the forbidden letters arrived, the butler would place them in the grand piano and deliver a bunch of violets to Marguerite to signal that post had arrived for her. And when Marguerite wanted to sneak out to meet such friends, she had the butler keep watch while she climbed out the first-story window.

Marguerite left Washington in 1908 when her father was transferred to Madrid. Marguerite danced around the continent, trying out the opera in Paris, getting married in Russia, being brought low by the Russian Revolution in Copenhagen, suffering poverty with two sons in Geneva, building a fashion empire in Florence… It wasn’t till 1937 that the Countess returned to America. It wasn’t like her initial triumphant arrival on the ship Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse almost 40 years ago; there were no swarming reporters, no pearls, no sparkling life awaiting her. The Great Depression had driven away the American customers of her fashion house and her family was barely making a living. The former belle skimped, saved and promoted her sons, Oleg and Igor. Just like in the old days, nothing could stand in Marguerite’s way. Oleg became a famous designer, well-known for creating Jackie Kennedy’s signature style. Igor was a famous reporter, writing a society gossip column for Cissy Patterson in DC.

In her 1956 memoir, Countess Cassini looked back on her roller-coaster of a life, on the glittering parties, her glamorous beaus, and everything she built and accomplished. Out of everything, what was Marguerite most proud of? Her boys, Igor and Oleg.

Sources

Cassini, Marguerite. Never a Dull Moment. (Harper & Brothers Publishing: 1956).

Morris, Edmund. Theodore Rex. (Random House: 2002).

Peyser, Marc. Hissing Cousins: The Untold Story of Eleanor Roosevelt and Alice Roosevelt Longworth. (Nan A. Talese: 2015).

“Social Precedence as Established by State and Countess Cassini’s Campaign of Conquest in the Diplomatic Corps.” The Washington Times. (Washington [D.C.]), 06 March 1904. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

“The Dashing Countess now a Sewing Woman.” The Washington Times. (Washington [D.C.]), 10 Dec. 1922. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

“Countess Cassini’s Next Appeal to Society: She hopes to break down social barriers through success on the operatic stage.” The Washington Herald. (Washington, D.C.), 10 May 1908. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

“Countess Cassini, Most Charming Lady of the Diplomatic Corps.” Los Angeles Herald, 13 April 1902. California Digital Newspaper Collection.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)