Remembering the First Smithsonian Folklife Festival

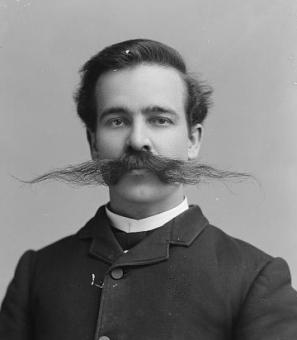

In January 1967, after just a few months on the job as the Smithsonian’s Director of Museum Services, Jim Morris had an idea.[1] What if the Smithsonian were to put on an outdoor festival in Washington to exhibit and celebrate folk traditions from around the nation?

The proposal was a departure from the sort of events that the Smithsonian generally sponsored in those days. But it meshed well with Secretary S. Dillon Ripley’s new vision that the Institution should be "bringing the museum out of its glass cases and into real life."[2] Ripley championed the festival idea and gained approval from the Smithsonian Board of Regents.[3] In May 1967, the Secretary allotted $4,900 (about $38,000 today) to finance the event, which was scheduled for July 1-4 on the National Mall.[4]

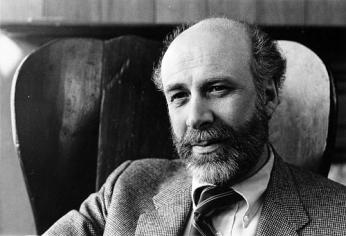

With just a few months to plan the festival and fill out the program, Morris hired a small staff including Ralph Rinzler, who had previously worked on the Newport Folklife Festival.[5] The group got to work immediately and Rinzler tapped into his network of artists from Newport. But, beyond those connections, finding acts was a grassroots effort, driven by word-of-mouth.

As Rinzler recalled later, "If you’re looking for musicians you start with a fiddlers’ convention or a regional music festival or a local fair. You ask a lot of questions and one guy gives you a name and that guy gives you another name and you just follow the trail."[6] The method was productive as the Smithsonian secured an astounding “fifty eight traditional craftsmen and thirty-two musical and dance groups” to participate in the 1967 Festival of American Folklife.[7]

As the festival’s opening day approached, Ripley and Festival staff were excited about the event, but not everyone in Washington was supportive. A contingent on Capitol Hill believed the festival — in addition to Ripley’s plans to erect a carousel on the Mall and inaugurate a kite flying contest — were “frivolous” and would “turn the Mall into a midway.”[8] Additionally, some museum curators worried that the festival, which emphasized the participants, threatened museum professionals' scholarly authority as subject matter experts.[9] Thankfully for festival organizers, the reaction from the public was much more positive.

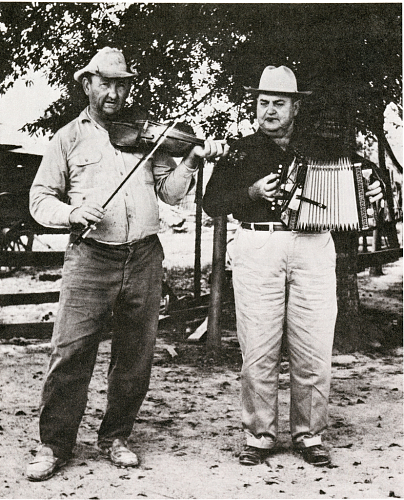

When the festival opened, visitors flocked to the Mall where they watched and talked with tradition bearers seated beneath circus tents or under the shade of trees. Musicians and dancers performed on small stages two feet off the ground with large audiences sitting, kneeling, or standing in front to watch and listen. Unlike future Festivals, there was no geographical or subject theme for the 1967 event. Acts included a family polka band from Texas, Mesquakie Indian performers from Iowa, Irish dancers from New York, and just about everything in between. (See the full list in the 1967 festival report.) In addition to watching folk demonstrations and performances, visitors could purchase traditional crafts at the Arts and Industries Building.

The four-day festival attracted an estimated 431,000 people, nearly doubling normal July Fourth visitation to the National Mall.[10] By just about all accounts, it was a resounding success. As one attendee put it, “The presentation of American folk song and dance afforded by the American Folklife Festival is one of simply unparalleled excellence. This festival fills a much needed gap and is an important contribution to the cultural life of the city and the Nation."[11] Representative Thomas M. Rees (D-California) echoed the sentiments, “My family and I found the entire festival both enlightening and educational, and I hope to see it again next year when we may have an even bigger and better all-American Fourth of July Festival.”[12]

Rees and the other enthusiasts would get their wish. After the success of the inaugural festival, the Smithsonian established the event as an annual tribute to American Folk Heritage on the National Mall.[13]

Over the past 50 years, the Smithsonian Folklife Festival (previously named the Festival of American Folklife)[14] has evolved from year to year but its focus on scholarship and celebration of grassroots arts has always remained paramount. Today the annual event attracts visitors and exhibitors from around the world. Perhaps the most enduring legacy of the Festival is that it led to the establishment of the Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage, which, in addition to researching and organizing the Festival each year, promotes “greater understanding and sustainability of cultural heritage across the United States and around the world through research, education, and community engagement.”[15]

Footnotes

- ^ "James R. Morris," Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage, accessed October 18, 2016, http://www.folklife.si.edu/legacy-honorees/james-r-morris/smithsonian

- ^ Ringle, Ken. “Of Lawyers and Other Folk: Even Barristers Join the Blend at the Smithsonian’s Festival of Diversity,” The Washington Post June 25, 1986 Accessed on October 24, 2016 ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Washington Post pg. D1 & D2 Col. 3

- ^ Kurin, Richard. "The Festival of American Folklife: Building on Tradition," 1991 Festival of American Folklife June 28-July 1, July l4-July 7 Smithsonian Libraries. p. 7 Accessed October 21, 2016. http://library.si.edu/digital-library/book/1991festivalofam00fest

- ^ "James R. Morris," Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage, accessed October 11, 2016, http://www.folklife.si.edu/legacy-honorees/james-r-morris/smithsonian

- ^ Fort, James. Ralph Rinzler Folklife Archives and Collections Finding Aid to the Ralph Rinzler Sound Recording Collection

- ^ Ringle, Ken. “Of Lawyers and Other Folk: Even Barristers Join the Blend at the Smithsonian’s Festival of Diversity,” The Washington Post June 25, 1986 Accessed on October 24, 2016 ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Washington Post pg. D1 & D2 Col. 3

- ^ 1967 Smithsonian Institution Festival of America Folklife: July 1-4 1967 Report. Smithsonian Institution 1967. Smithsonian Libraries, p. 1 Accessed October 26, 2016. http://library.si.edu/digital-library/book/festivalofameric00festi

- ^ Kurin, Richard. "The Festival of American Folklife: Building on Tradition," 1991 Festival of American Folklife June 28-July 1, July l4-July 7 Smithsonian Libraries. p. 8 Accessed October 21, 2016 http://library.si.edu/digital-library/book/1991festivalofam00fest

- ^ Kurin, Richard. "We are Very Much Still Here!," 40th annual Smithsonian Folklife Festival Washingto, D.C., June 30-July 11, 2006.Smithsonian Institution Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage, 2006. Smithsonian Libraries p.10

- ^ 1967 Smithsonian Institution Festival of America Folklife: July 1-4 1967 Report. Smithsonian Institution 1967. Smithsonian Libraries, p. 1 Accessed October 26, 2016. http://library.si.edu/digital library/book/festivalofameric00festi

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “The Festival had been presenting international programs since the early 1970s, and in 1998, we changed the name to Smithsonian Folklife Festival to reflect that global scope”. Parker, Diana. “On the Occasion of Our 40th Festival,” 40th annual Smithsonian Folklife Festival, Washington, D.C., June 30-July 11, 2006, page 8. Smithsonian Institution Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage, 2006. Electronic resource accessed on October 21, 2016. http://library.si.edu/digital-library/book/40thannualsmiths00smit

- ^ Mission and History Web Page of the Smithsonian Center of Folklife and Cultural Heritage. http://www.folklife.si.edu/mission-and-history/cfch-strategic-plan/smithsonian

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)