Washington Rolls Out the Red Carpet for Charles Lindbergh

When word came from Paris that Charles Lindbergh successfully completed the first trans-Atlantic flight on May 21, 1927, the world celebrated. Overnight the young pilot became a household name and hero. Cities around the globe prepared to fête him and Washington was no exception.

Indeed, the engine in Lindbergh’s The Spirit of St. Louis airplane was probably still warm when officials began planning to greet the “conqueror of the Atlantic” in the Nation’s — even though he had yet to announce whether he planned to visit Washington upon his return from Europe. But as local American Legion adjutant, William Franklin, surmised, it was difficult to imagine that the pilot wouldn’t come to Washington on the heels of his record-setting flight. “We were sure he would get there. And we are just as sure now that he will come here. Every other national hero has come here at one time or another, hasn’t he?”[1]

Franklin’s words proved to be prophetic.

Within a few days, news broke that Lindbergh would not only be coming to Washington but that it would be his first stop back in America. He and his plane would arrive June 11, as passengers on the USS Memphis, after a tour of Europe and a week-long voyage across the Atlantic. (Considerably slower than the 33 ½ hours it had taken him to go from New York to Paris by air!)

D.C. was — in a word — ecstatic. As the Washington Post put it,

Nowhere in America has Lindbergh’s triumphant flight evoked more fervent enthusiasm than here in the Nation’s city, and no individual, American or foreign, has ever received a more rousing welcome than will be accorded him. It is fitting that Capt. Lindbergh should come first to Washington.”[2]

(New York — it should be noted — was less excited about the scheduling. Since Lindbergh’s flight had started in NYC, many there hoped the Big Apple would be his first stop upon returning to the U.S.)[3]

Government and business leaders formed an official Lindbergh reception committee to make sure the D.C. visit went off without a hitch. The committee lined up a full itinerary for the young flyer, including: a military parade down Pennsylvania Avenue, a Presidential medal ceremony, a state dinner, a wreath-laying at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, and a visit with disabled veterans at Walter Reed.[4] The Evening Star accepted donations from citizens interested in helping fund the reception, which was expected to cost $15,000, and turned them over to the reception committee.[5]

Even “ultra-conservative” forecasters predicted that the reception would attract over 100,000 out-of-towners, coming from up and down the eastern seaboard and as far west as Cleveland.[6] Railroad companies were quick to schedule additional “Lindbergh special” runs to D.C. As the Evening Star noted, “There is an intense rivalry between competitive railways and the Pennsylvania and Baltimore & Ohio are making special effort to take advantage of the popular desire on the part of Easterners to make a day of it in Washington.”[7]

Silent newsreel of Lindbergh's arrival in Washington

By the time the Memphis came chugging up the Potomac River on the morning of June 11, Washingtonians could hardly contain themselves. Huge crowds gathered by the water’s edge and the Washington Boys Independent Band claimed the honor of being the first in the area to salute Lindbergh, playing “The Star-Spangled Banner” as the ship passed Alexandria.[8]

For Lindbergh, the scene was pretty overwhelming. As he told Vice-Admiral Guy Burrage on board the ship, “It is a great and wonderful sight and I wonder if I really deserve all this.”[9] But, whether he thought he was deserving or not, the euphoria was just beginning.

When the Memphis steamed into the Washington Navy Yard around 11:20 a.m., “amidst the blare of guns and of bands and the cheers of thousands,”[10] excited greeters broke through the ropes and pressed close to the gangplank. Lindbergh waved from the ship before briefly retiring below deck to meet his mother, Evangeline, who was brought aboard. After a short private reunion, the Lindberghs were escorted off the ship to a waiting car, joined by John Hays Hammond, chairman of the reception committee. After maneuvering through the crowd, the car joined a military parade, which marched from Capitol Hill to the Washington Monument grounds. The route was “a surging ocean of flags” and “Pennsylvania Avenue to the Treasury [building] was lined by two unbroken walls of humanity,” according to the Star.[11]

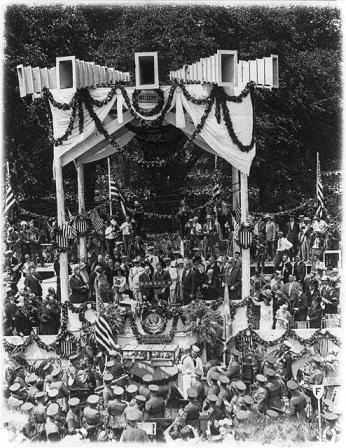

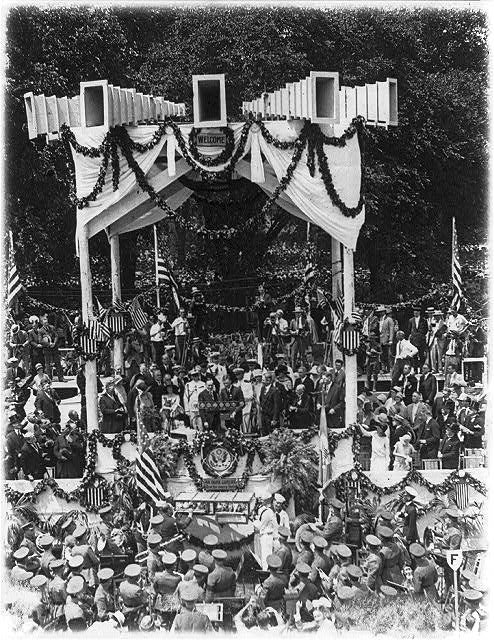

The guest of honor arrived at the Monument at approximately 12:45 p.m. and was shown to his seat next to President Calvin Coolidge on a stage. Before an estimated crowd of 200,000, the President welcomed Lindbergh home as “an illustrious citizen of our Republic, a conqueror of the air and strengthener of the ties which bind us to our sister nations across the sea.”[12] He then presented Lindbergh with the Distinguished Flying Cross, the nation’s highest aviation honor. Lindbergh thanked the President and the crowd for the honor. Following the remarks, 48 pigeons were released (symbolizing the 48 states in the union) and a pyrotechnics display in which flags and “funny puffed up animals” attached to small parachutes were launched over the crowd.[13]

By all accounts, it was quite a spectacle. As the Star noted, “Washington has witnessed far greater parades in numerical numbers, but never had the city poured out its welcome in such lavish fashion to a returning hero.”[14]

After the ceremony, Lindbergh, his mother, and the first family were whisked off to the Patterson Mansion at Dupont Circle, which was serving as President Coolidge’s temporary residence while the White House was undergoing renovations. There, too, the aviator was met with huge crowds who chanted “We want Lindy!” until he stepped out on the mansion’s balcony to wave.

It was more of the same for the rest of his visit. As he made his way from event to event, Washingtonians clamored for a glimpse of him. As one newspaper account put it, “Washington’s hero worshiping populace seemed to know no limit in their affectionate welcome.”[15]

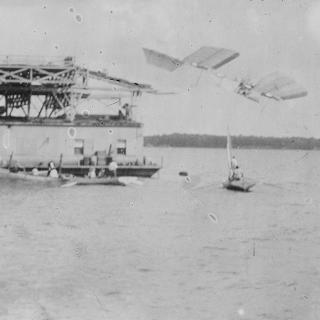

As all of this was going on, mechanics at the Anacostia Naval Air Station were busily reassembling The Spirit of St. Louis so that it could be put on display on a floating barge near Hains Point. (The plane had been dismantled for the voyage back to the U.S.) Motorists were invited to drive their cars around West Potomac Park and view the plane that made history. So many came that “the slowness with which the traffic moved gave those in automobiles an opportunity to get a good view of the plane,” once they finally reached it.[16]

Lindbergh was certainly impressed with the outpouring he received in Washington. And, it was a homecoming in more ways than one. Not only was he returning to the United States after his momentous flight but he was returning to a city where he had spent a portion of his youth. The family had lived in Washington for a time while the flyer’s father was a Congressmen from Minnesota. During that time, the younger Lindbergh attended Sidwell Friends School.

On June 12, The Evening Star printed a column, which the pilot penned himself expressing gratitude for the warm welcome.

Paris was marvelous and London and Brussels as well, and I wouldn’t for the world draw any comparisons, but I will say this, the Washington reception was the best handled of all.”

He continued, “It was 11 years since I had been in Washington. It feels good to see it again. I recognized a lot of familiar places immediately. I was particularly pleased to pass my old school and the apartment house where I used to look up at the big Capitol just across the park.”[17]

The next morning, he flew to New York for the second of many fêtes, which would be held in his honor around the country. But Lindbergh and his famous plane would return to Washington a few years later. In 1928, he gifted The Spirit of St. Louis to the Smithsonian and delivered it personally, landing it at the old Bolling Field in Southeast Washington. Since 1975, it has resided in the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum.[18]

Footnotes

- ^ “Capital Ready to Greet Conquerer of the Atlantic,” The Washington Post, 24 May 1927: 3.

- ^ “Lindbergh’s Welcome Home,” The Washington Post, 2, Jun 1927: 6.

- ^ “New York Will Ignore Washington Reception, The Washington Post, 3 Jun 1927: 3.

- ^ “Reception to Lindbergh,” The Washington Post, 4 Jun 1927: 4.

- ^ “Trade Bodies Aid in Lindbergh Fund,” The Evening Star, 3 Jun 1927: 4.

- ^ “Capital Plans to Welcome Huge Throng of ‘Lindy’ Fans,” The Evening Star, 8 Jun 1927: 3.

- ^ “Capital Plans to Welcome Huge Throng of ‘Lindy’ Fans,” The Evening Star, 8 Jun 1927: 3.

- ^ “Sidelights Gleaned From City’s Reception to Col. Lindbergh,” The Washington Post, 12 Jun 1927: M9.

- ^ “Colonel Expresses Doubt to Admiral Burrage as Escort Comes,” The Washington Post, 11 Jun 1927: 1.

- ^ “Verbatim Report of Lindbergh Day As Broadcast by Radio,” The Washington Post, 12 Jun 1927: M8.

- ^ “Parade Swiftly Moves on Signal,” The Evening Star, 11 Jun 1927: 2.

- ^ “Cheering Thousands Hail Lindbergh in Triumpal Parade Along Avenue,” The Evening Star, 11 Jun 1927: 1-2.

- ^ “Verbatim Report of Lindbergh Day As Broadcast by Radio,” The Washington Post, 12 Jun 1927: M8. See also “Cheering Thousands Hail Lindbergh in Triumpal Parade Along Avenue,” The Evening Star, 11 Jun 1927: 1-2.

- ^ “Cheering Thousands Hail Lindbergh in Triumpal Parade Along Avenue,” The Evening Star, 11 Jun 1927: 1-2.

- ^ “Cheering Thousands Hail Lindbergh in Triumpal Parade Along Avenue,” The Evening Star, 11 Jun 1927: 1-2.

- ^ “Lindbergh Plane Attracts Throng,” The Washington Post, 13 Jun 1927, 3.

- ^ “Lindbergh Lauds Capitol Welcome as Best Handled,” The Evening Star, 12 Jun 1927: 1.

- ^ Ruane, Michael E. “At 89, The Spirit of St. Louis Gives Up Some Long Held Secrets,” The Washington Post, 27 Jun 2016.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)