Mister Rogers Comes to Washington

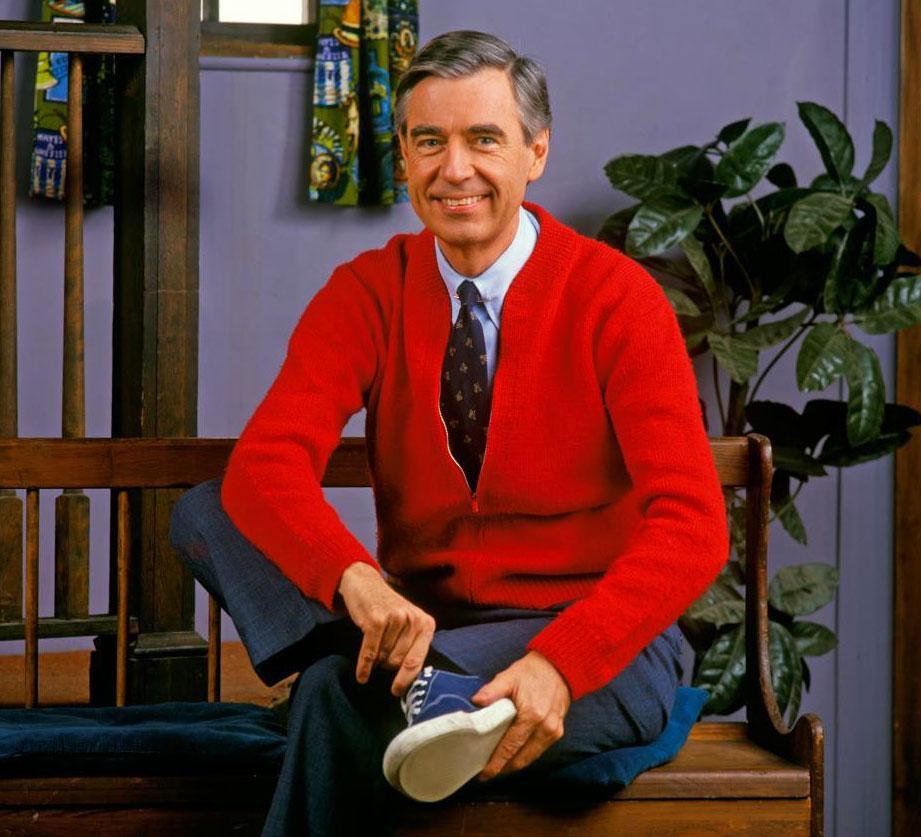

Fred Rogers, creator and host of the longtime children's television landmark Mister Rogers' Neighborhood, is most closely associated with Pittsburgh, where he produced 886 episodes of his program at local PBS station WQED over a period of more than 30 years. He made two very significant visits to Washington, D.C., however, one near the beginning of his career, and the second towards the end of his life.

Mister Rogers' Neighborhood premiered nationally on February 19, 1968 on National Educational Television (NET), the precursor to PBS. Just over a year later, Rogers traveled to Washington, D.C., to defend funding for the Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB), which had been established by an act of Congress signed by President Lyndon Johnson on November 7, 1967.

On May 1, 1969, Rogers testified before the Senate Subcommittee on Communications to argue against a proposal by President Richard Nixon to cut federal funding for public broadcasting from $20 million to $10 million. The committee’s chair, powerful Democratic Sen. John O. Pastore of Rhode Island, clearly had never heard of Rogers or his show, and appeared gruff and impatient when he invited Rogers to present his case, kicking off with a brusque "Alright Rogers, you've got the floor." Pastore himself was no stranger to the art of impassioned oratory, having delivered what many considered to be the strongest speech of the 1964 Democratic Convention:

His voice rising and falling to great dramatic effect, his fists pounding, Mr. Pastore drew roars from the more than 5,000 Democrats at the Atlantic City Convention Hall as he denounced Senator Barry Goldwater, the Republican nominee, as a captive of ''reactionaries and extremists.'' The response to Mr. Pastore's speech was so enthusiastic that he enjoyed a brief consideration for the vice presidential nomination that eventually went to Senator Hubert H. Humphrey.1

Despite his impressive resume as a speaker, Pastore could not possibly have anticipated the power of the patient, genteel and focused presentation he was about to receive from the soft spoken Fred Rogers. In a mere six minutes of testimony, Rogers delivered what some believe to be a masterclass in persuasive argument, one that employed the authenticity, respect and emotional intelligence that characterized his unique approach to educating children.2

After beginning by establishing his trust and empathy for Pastore, Rogers gave a brief summary of how his program had benefited from the infusion of federal funding into the public broadcasting system — it had grown from a budget of just $30 to $6,000. To make a stark comparison, he added that his program's entire yearly cost was equal to "less than two minutes of cartoons," referred to by Rogers as "animated ... bombardment."3 He then pivoted to his educational philosophy and what he hoped to accomplish through children's television:

I’m very much concerned, as I know you are, about what’s being delivered to our children in this country. And I’ve worked in the field of child development for six years now, trying to understand the inner needs of children. We deal with such things as — as the inner drama of childhood. We don’t have to bop somebody over the head to…make drama on the screen. We deal with such things as getting a haircut, or the feelings about brothers and sisters, and the kind of anger that arises in simple family situations. And we speak to it constructively...

I give an expression of care every day to each child, to help him realize that he is unique. I end the program by saying, “You’ve made this day a special day, by just your being you. There’s no person in the whole world like you, and I like you, just the way you are.” And I feel that if we in public television can only make it clear that feelings are mentionable and manageable, we will have done a great service for mental health.

Rogers wrapped up by reciting the lyrics to "What Do You Do with the Mad that You Feel?", one of the many songs he had written for his show. By this point, the initially standoffish (and possibly bored) Pastore had grown increasingly engaged and sympathetic. Once the recitation had concluded, Pastore declared, “I think it’s wonderful. I think it’s wonderful. Looks like you just earned the $20 million.” As a result, the next major congressional appropriation in 1971 increased CPB's funding from $9 million to $22 million.4 You can watch the testimony in its entirety below:

Rogers' second visit to Washington was much more celebratory and less fraught with tension and drama. After a lifetime of achievement educating and inspiring generations of children, he had come to receive the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the Nation's highest civilian honor, at a White House ceremony on July 10, 2002. Before presenting Rogers with his medal, President George W. Bush honored him with the following words:

Fred Rogers has proven that television can soothe the soul and nurture the spirit and teach the very young. "The whole idea," says the beloved host of Mr. Rogers' Neighborhood, "is to look at the television camera and present as much love as you possibly could to a person who needs it." This message of unconditional love has won Fred Rogers a very special place in the heart of a lot of moms and dads all across America. 5

Not long after the White House ceremony, Rogers' health began to decline, and he died from stomach cancer on February 27, 2003, at age 74. A few months before his death, Rogers entered the WQED studios for the final time and recorded a touching video message for those who grew up watching Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood:

I would like to tell you what I often told you when you were much younger. I like you just the way you are. And what’s more, I’m so grateful to you for helping the children in your life to know that you’ll do everything you can to keep them safe. And to help them express their feelings in ways that will bring healing in many different neighborhoods. It’s such a good feeling to know that we’re lifelong friends.

The non-profit Fred Rogers Productions carries on his legacy today through its multimedia work producing award-winning children’s series such as Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood, Alma's Way, Donkey Hodie, Peg + Cat, and Odd Squad, all presented locally on WETA PBS Kids.

Footnotes

- 1

Goldstein, Richard. "John Pastore, Prominent Figure in Rhode Island Politics for Three Decades, Dies at 93." The New York Times, July 17, 2000. Accessed February 27, 2018.

- 2

Greave, Jean. "How Emotional Intelligence Landed Mr. Rogers $20 Million." TalentSmart. Accessed February 28, 2018

- 3

Silva, Ernesto. "Won't you be my neighbor?" Corporation for Public Broadcasting. August 18, 2015. Accessed March 01, 2018.

- 4

"CPB's Past Appropriations." Corporation for Public Broadcasting. February 12, 2018. Accessed March 01, 2018.

- 5

"George W. Bush: Remarks on Presenting the Presidential Medal of Freedom - July 9, 2002." The American Presidency Project. Accessed February 28, 2018.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)