The Pork Chop That May Have Saved the World

My fellow citizens: let no one doubt that this is a difficult and dangerous effort on which we have set out. No one can foresee precisely what course it will take or what costs or casualties will be incurred. Many months of sacrifice and self-discipline lie ahead— months in which both our will and our patience will be tested— months in which many threats and denunciations will keep us aware of our danger. But the greatest danger of all would be to do nothing.

--President John F. Kennedy, October 22, 1962

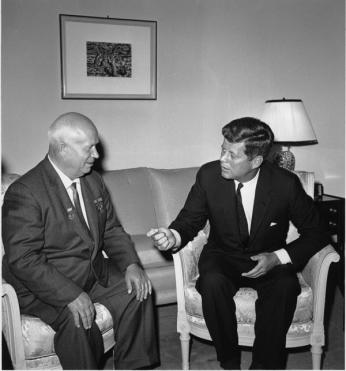

President Kennedy spoke these words during a televised address on October 22, 1962, as he informed American citizens of Soviet missile sites in Cuba. He didn’t know at the time that the months-long scare he was referring to would be over just six days later. Four days after JFK’s speech, two men sat down to lunch at the Occidental Restaurant located two blocks from the White House. One ordered a pork chop and the other crab cakes. Despite how it may seem, this was no ordinary lunch. In fact, it is considered to have played a major role in ending the Cuban Missile Crisis.

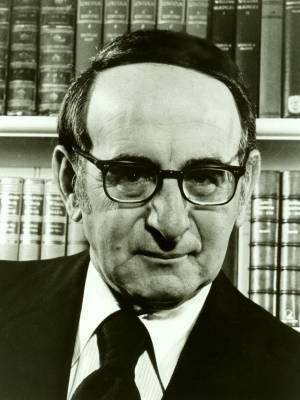

On Friday morning, October 26, 1962, ABC News Correspondent John Scali received a call from an unidentified Russian man whom Scali believed to be the chief of Soviet intelligence in the United States. This man, often referred to as “X,” was later identified as Aleksandr Fomin, the counselor of the Soviet Embassy.[1] In an urgent and insistence voice, Fomin asked Scali to have lunch. Although years later Scali admitted that he’d already eaten lunch that day, he agreed to meet because of the urgency in Fomin’s voice.[2] Scali and Fomin agreed on the Occidental Restaurant next to the Willard Hotel for the mysterious lunch.

The Occidental Restaurant enjoyed a rich history of its own and was no stranger to high profile diners. Henry Willard, founder of the historic Willard Hotel, opened the Occidental next to his hotel in 1906.[3] The restaurant was initially run by Gustav Buchholz, a German immigrant working as head waiter at the Willard. In 1912, Buchholz was made the owner of the restaurant and took to lining the walls with photographs of famous patrons, including presidents, senators, executive cabinet members, and sports and literary greats.[4] These high profile visitors helped the restaurant earn the reputation as the place “where statesmen dine.”[5]

At 1 p.m. on Oct. 26, Scali and Fomin arrived at the Occidental and sat at a “table on the left-hand side against the wall.”[6] When the waiter came to take their order, Scali ordered crab cakes, and Fomin ordered a pork chop. Once they placed their order, Fomin began talking about the urgent situation regarding Cuba. Scali later recounted the conversation on ABC News in 1964:

“[Fomin] came right to the point and said, ‘War seems about to break out; something must be done to save the situation.’

And I said, ‘Well, you should have thought of that before you introduced the missiles.’

He then said, ‘There might be a way out; what would you think of a proposition whereby we would promise to remove our missiles under United Nations inspection, where Mr. Khrushchev would promise never to introduce such offensive missiles into Cuba again? Would the President of the United States be willing to promise publicly not to invade Cuba?’

I said I didn’t know, but I would be willing to try and find out.” [7]

Their food arrived following this exchange. By mistake, the waiter gave Scali’s crab cakes to Fomin, and Scali received the Russian counselor’s pork chop instead. Apparently, Fomin didn’t notice and kept the crab cakes without saying a word; the rest of the meal was eaten in complete silence.[8]

At 6 p.m. the same day, before Scali was able to inform the administration about the lunch conversation, the U.S. State Department received a telegram from the U.S. embassy in Moscow that appeared to be written by Khrushchev himself. Interestingly, the letter contained that same settlement proposal that Fomin had suggested to Scali earlier in the day. Within the long, dramatic telegram, Khrushchev wrote:

“I propose: We, for our part, will declare that our ships, bound for Cuba, will not carry any kind of armaments. You would declare that the United States will not invade Cuba with its forces and will not support any sort of forces which might intend to carry out an invasion of Cuba. Then the necessity for the presence of our military specialists in Cuba would disappear." [9]

Scali was able to tell Secretary of State Dean Rusk about the conversation he had with Fomin around 6:45 p.m. that evening, which led U.S. officials to assume that Fomin’s message was initiated by Khrushchev and that the lunch was supposed to be a “set-up” for the letter to come in the evening. In the aftermath of the crisis, however, this assumption was deemed to be incorrect, as officials concluded that Fomin was likely working without official backing from Khrushchev. Reflecting upon the incident years later, Fomin admitted as much, “The mistake the Americans made was to overestimate my own authority. I was speaking as a mere analyst while they saw me as a Kremlin spokesman.”[10]

The Kennedy Administration used Scali as a go-between with Fomin for the next few days, having Scali recite messages from Secretary Rusk, which Fomin claimed to be immediately relaying to high Soviet sources.[11] Finally, the immediate fears of the Cuban Missile Crisis were averted on October 28, 1962, when the Kennedy Administration, still assuming a set-up from the Kremlin, acted in accordance with Khrushchev’s wishes and agreed not to invade Cuba, and also secretly agreed to remove the U.S.’ missiles in Turkey.[12] In return, Khrushchev agreed to remove all nuclear missiles from Cuba, ultimately ending the scare of worldwide nuclear destruction.

Although the precise amount of weight that Scali and Fomin’s Occidental lunch had on ending the Cuban Missile Crisis is generally debated, their risky conversations are still considered to be crucial factors in helping control the crisis. In fact, if you go to the Occidental Restaurant today, despite their recent remodel, you can still see a brass plaque on the table commemorating the lunch:

“At this table during the tense moments of the Cuban missile crisis a Russian offer to withdraw missiles from Cuba was passed by the mysterious Russian ‘Mr. X’ to ABC-TV correspondent John Scali. On the basis of this meeting the threat of a possible nuclear war was avoided.” [13]

Footnotes

- ^ Aleksandr Fomin was the cover name that Aleksandr Feklisov used while he worked as the KGB (Soviet security agency) station chief in Washington D.C. from 1960-1964.

- ^ “John A. Scali, 77, ABC Reporter Who Helped Ease Missile Crisis - NYTimes.Com.” Accessed January 24, 2018. http://www.nytimes.com/1995/10/10/us/john-a-scali-77-abc-reporter-who-h….

- ^ “The Willard Hotel.” WHHA. Accessed January 24, 2018. https://www.whitehousehistory.org/the-willard-hotel.

- ^ “History - Occidental Grill & Seafood.” Accessed January 24, 2018. http://www.occidentaldc.com/history/.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Garmarekian, Barbara, and Special to the New York Times. 1986. “Washington Talk; Old Friend Returns, Rich in Mystique.” The New York Times, October 27, 1986. http://www.nytimes.com/1986/10/27/us/washington-talk-old-friend-returns….

- ^ “John A. Scali, 77, ABC Reporter Who Helped Ease Missile Crisis - NYTimes.Com.” Accessed January 24, 2018. http://www.nytimes.com/1995/10/10/us/john-a-scali-77-abc-reporter-who-h….

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “Department of State Telegram Transmitting Letter From Chairman Khrushchev to President Kennedy, October 26, 1962.” 1962. October 26, 1962. http://microsites.jfklibrary.org/cmc/oct26/doc4.html.

- ^ Martin, Douglas. 2007. “Aleksandr Feklisov, Spy Tied to Rosenbergs, Dies at 93.” The New York Times, November 1, 2007, sec. Europe. https://www.nytimes.com/2007/11/01/world/europe/01feklisov.html.

- ^ “Cuban Missile Crisis Chronology.” The National Security Archive, The George Washington University. Accessed March 6, 2018. https://nsarchive2.gwu.edu//nsa/cuba_mis_cri/621026_621115%20Chronology….

- ^ Andrew Glass. “Cuban Missile Crisis Ends, Oct. 28, 1962.” POLITICO. Accessed March 6, 2018. https://www.politico.com/news/stories/1010/44263.html.

- ^ “1962 - Occidental Grill & Seafood.” Accessed January 24, 2018. http://www.occidentaldc.com/history/timeline/1962/.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)