Remembering Ham: The National Zoo's Very Own "Astrochimp"

If you visited the National Zoo in 1975, you would have had the honor of meeting some of Washington’s greatest animal icons. Ling-Ling and Hsing-Hsing consumed Washington in Panda-monium.1 Smokey Bear still had some time left in this world.2 But you’d be forgiven for missing the unassuming chimpanzee sitting alone in his barren cage. From the looks of him, you wouldn’t know that you were witnessing one of America’s most historic animals, the ape who proved that humans could travel into space.

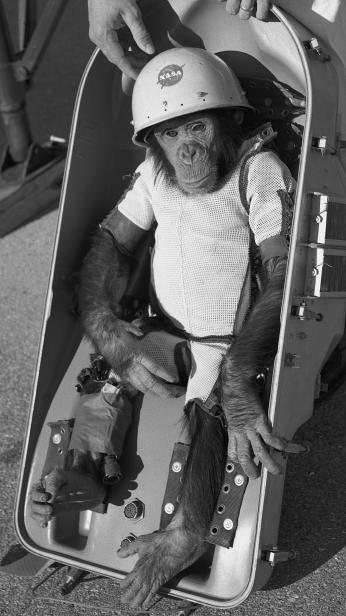

By the time Ham retired to the National Zoo in 1963, the six-year-old chimp had already achieved an enviable career milestone. On January 31, 1961, he was blasted 157 miles above the Earth atop the Mercury-Redstone 2 rocket from its launchpad in Cape Canaveral, Florida. NASA had sent dogs and monkeys before him, including fellow National Zoo retirees Patricia and Mike, the Philippine macaques. But no animal could simulate the effects of prolonged weightlessness on the human body better than a species that shares 98% of our DNA. The precocious three-year-old Ham graduated from NASA’s “School for Space Chimps” at the top of his training class from about forty other astrochimp candidates.

Ham lived at Holloman Air Force Base in New Mexico for over fifteen months before the Mercury-Redstone 2 mission. He wasn’t Ham then, just “No. 65”, a baby chimp purchased by the Air Force from a breeding farm in Miami, though he was likely born in the jungles of French Cameroon in 1957. No. 65 was sparingly named to discourage the public and his handlers from becoming attached to the animal should he die in a failed mission. The engineering required to launch the chimp into space was a monumental feat of human ingenuity. No. 65’s job in comparison, would be simple.

He had to sit strapped into a chair in a small capsule for hours at a time. He was trained to pull levers in sequences within five seconds of light and sound cues that flashed from his capsule. Getting the sequence right in under five seconds would prove that if a chimp could do it, humans could perform complex motor tasks in space. No. 65 earned a banana pellet for getting the sequence right. Getting it wrong would elicit electric shocks to his feet.

“He was wonderful,” recalled Edward Dittmer, one of No. 65’s trainers. “He performed so well and was a remarkably easy chimp to handle. I’d hold him and he was just like a little kid.”3 The choice between No. 65 and six other space chimp candidates was close, but in the dawn hours of January 31, No. 65 was ultimately selected for his intelligence and exceptionally calm demeanor.

The lucky (perhaps) astrochimp was strapped into a nylon spacesuit, fitted with sensors (including one in his rectum) and secured into the same aluminum capsule he had trained in for 219 hours over fifteen months. Ten hours later, at 11:55 A.M., No. 65 rocketed into the atmosphere at 5,857 miles per hour. His suborbital spaceflight lasted just sixteen minutes. But due to a rocket malfunction, he accelerated and re-entered Earth’s atmosphere much faster than anticipated, experiencing six minutes and 17gs of weightlessness. The capsule overshot its splash point by 130 miles. No. 65 returned to our planet of apes to a hero’s welcome. When the Navy retrieved his capsule from the Atlantic, he shook hands with sailors and was rewarded with an apple for his courage. He looked just as unperturbed as when he left Earth. His seeming nonchalance didn’t last. When his handlers tried to force him back into his capsule to pose for photos by the press, he panicked.4 “I have never seen such terror on a chimp’s face,” the famed primatologist Jane Goodall said when she saw the photos.5

Besides suffering an abrasion on his nose and losing five percent of his body weight, medical examiners gave No. 65 a clean bill of health. Remarkably, he had performed his lever-pulling tasks with gusto, proving that humans could perform complex mental and physical tasks in space. No. 65 was given a proper name only after his survival. The name Ham came from the Holloman Aerospace Medical Center, and the nickname for the lab’s commander.

Although the Mercury-Redstone 2 mission didn’t go exactly as planned, it was one giant leap for man (and chimp) kind. Ham paved the way for Alan Shepard to become the first American to launch into space just four months later.

The Air Force kept Ham for the following two years to monitor him for any long-term effects after his journey into space. NASA ruled out training him for a second mission when he fought to avoid getting strapped back into his capsule. Alas, Ham’s space travel days were over.6 Having served his country admirably, the Air Force transferred him to the National Zoological Park on April 5, 1963.

Nobody rolled out the red carpet for Ham, like the D.C. press and public did for Smokey Bear and Nixon’s pandas. He moved next to four other chimpanzees, but he lived by himself in a 10’ x 14’ cage, about as big as your average garden shed. “He seems to have adjusted nicely to his comparatively quiet routine in the Zoo’s ape quarters,” the Smithsonian described in their 1963 Annual Report.7 Others had a different perspective. “He was so lonesome looking, he made me cry,” eight-year-old Lori Lee Pyke told The Washington Post when she visited the zoo a year after Ham’s arrival.8

The zoo affirmed that it had tried valiantly to improve Ham’s life. Zookeepers stocked his cage with furniture, only for Ham to smash it. They moved his next-door neighbor Maggie in with him to spark a possible romance, only for Ham to shun the female chimp with “a lack of interest bordering on insult”.9 The zoo couldn’t say with any certainty whether Ham’s space trip had anything to do with his lack of ardor. Then again, the only female chimp the zoo had available was three times older than Ham. Maggie chose their rambunctious neighbor Jiggs for a mate instead. The zoo couldn’t room Ham with Jiggs due to the tendency for male chimps to fight. But the zoo didn’t give up entirely.

Maggie became pregnant in April 1964 and may have been moved in with Ham for a second try. The zoo also considered Lulu, a three-year-old female who had several years to go before reaching sexual maturity, but Ham acted like he had all the time in the world.10

Ham may never have found companionship at the National Zoo among his own kind, but he got quite the attention from members of the opposite species. Eight months after his arrival, a British philatelist (an expert on postal stamps, cards and marks) wrote a letter to the zoo requesting a signed autograph from Ham on an envelope, in the form of a foot or handprint. In 1968, an anonymous correspondent sent Ham a Valentine’s Day card, enclosed with a poem. In the 1960s or 70s, the Chapultepec Zoo in Mexico purchased a chimpanzee they were fraudulently led to believe was Ham. The zoo displayed the chimp for several years before they found out that they had been duped.11 Ham briefly pulled out of retirement to appear on TV shows and cameo in a movie with stunt performer Evel Knievel.12

To truly understand Ham's life in captivity, we have to step back and examine the status of zoos in the mid-20th century. There were few natural habitats and messages of conservation like you see today. There were iron-bar cages hardly bigger than your living room. This was the age when baby chimps were dressed up for tea parties and animals were captured from the wild in nets, before environmentalism changed our understanding of our ethical responsibilities to the natural world. Animals weren’t seen as natural treasures vital to our planet’s health, they were objects of voyeurism showcased as scientific curiosities. The amusement of guests was prioritized above all else, animal welfare included.13

But the National Zoo was created to be different. Esteemed hunter and conservationist William Temple Hornaday founded the zoo in the 1890s with the mission of preserving America’s vanishing wildlife.14 Just after Ham’s arrival in the mid-1960s, this mission expanded to ensuring the survival of endangered species around the world and studying animal reproduction. The zoo pioneered the study of conservation genetics, which allows zoos to match animals around the world to breed and spread genetic diversity in endangered populations. It implemented an ambitious master plan of capital improvements and environmental education beginning in 1962.15

By the 1960s, zoos were finally catching up to the fact that thousands of charismatic species around the world were headed for extinction, chimpanzees included. But it would be decades before they developed institutionalized standards to adequately care for those species in captivity.16

Indeed, Ham's stay in D.C. was pretty lonely. He lived by himself in a cage for much of the zoo’s expansion and rebranding.17 Visitors in 1975 would have seen an overweight chimp with bald spots and a graying beard lazing on a concrete floor surrounded by walls and iron bars.18 Ham’s endurance at the National Zoo finally came to an end on September 20, 1980, when he was transferred to the North Carolina Zoo in Asheboro. He had lived alone in a cage for the better part of seventeen years. But Ham’s life finally started to look on the upswing. He joined a small troop of chimps in North Carolina and might have even struck up a friendship with a young female.19 Sadly, his new lease on life proved to be short-lived.

Ham died on January 19, 1983, at the estimated age of 26. He was between 50 and 60 in human years.20 He bore no children and has no living relatives. His remains were delivered to the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology (AFIP) in Washington, D.C. Pathologists from the AFIP and National Zoo conducted a necropsy, revealing that Ham died of chronic heart and liver disease. The pathologists took careful measures to preserve his skin in good condition. The US Air Force still owned Ham and decided that America’s space pioneer was destined to be taxidermied and exhibited in the International Space Hall of Fame at the Museum of Space History in New Mexico.21

The press and public were in an uproar. “Talk about death without dignity,” wrote The Washington Post. “Talk about dreadful precedents - it should be enough to make any space veteran more than a little nervous about how he is treated in the posthumous by and by . . . How about treating America’s First Ape with a little respect? Bury Ham."22

A high school sophomore from New York sent a letter to the AFIP, taking care to cc the National Zoo, Air and Space Museum, and the Museum of Space History. “By treating his body like that of a stupid beast, people will continue thinking of apes as stupid beasts, and not the intelligent, almost human animals they really are. In my opinion, a gravestone would honor Ham’s life much better than would having his body filled with sawdust and stuck under a glass case for countless years to gather dust.”23

So, it would be. “You will be happy to learn that following our initial decision, the question was reconsidered, and it was decided not to stuff and display him as originally planned,” wrote an Air Force lieutenant colonel in response to the high schooler’s letter.24 Ham’s skin and organs were cremated and today lay buried under a bronze plaque at the Museum of Space History.

The museum wrote a letter to Alan Shepard inviting him to the burying ceremony, saying, “I don’t know if you’re an animal lover or not – or how much you feel our space program owes the primates who first proved man could survive in space. I do know that you had to cope with a lot of jokes and sometimes ‘unfunny’ humor about the situation. And, perhaps, now would be a good time to give a timely and dignified response to these innuendoes and, at the same time, create some goodwill for the United States space program.”25

Shepard declined. It’s possible that he didn’t attend because he begrudged Ham for delaying his launch, allowing Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin to become the first human in space.26

The Air Force reportedly kept Ham’s skeleton for its “scientific value”, where it joined the remains of other military test animals like Able the space-flying Rhesus macaque. Today, Ham’s bones lay in a drawer behind-the-scenes of the National Museum of Health and Medicine in Silver Spring, Maryland.27

While the necropsy indicated that Ham never suffered any long-term physical effects from his space flight, his mental health is harder to decipher. After all, when Ham was captured from the wild and forced to cooperate with humans, he was just a baby. Ham spent the formative years of his development in the company of humans. He was trained to fly into space at the same time he still needed to nurse from his mother, who may have been killed by trappers before he was taken from the jungles of French Cameroon.28

Ham never got the happy retirement he deserved, but the National Zoo is unlikely to repeat the mistakes of the past. The zoo transformed into a world-renowned innovator in wildlife conservation and modern zoo design.29 The chimps are gone, but so are the cages. Gorillas and orangutans perform natural behaviors and demonstrate their remarkable intelligence in the modern Great Ape House and one-of-a-kind Think Tank museum. Amazonia and Asia Trail immerse visitors in naturalistic recreations of wild habitats and educate guests about the need to preserve Earth’s biodiversity. Smokey Bear’s old grotto persists as a historic reminder of how far the zoo has come, before guests embark on the spectacular American Trail. Even the pandas are back after a brief hiatus.

Hollywood memorialized Ham’s achievements in films spanning the decades, including The Right Stuff30 and 2024’s Fly Me to the Moon.31 Buzz Aldrin believes America owes an enormous debt to Ham and the space chimps. “They, and their descendants, have served us in so many ways, initially as substitute humans in space research. Now it is time to repay this debt by giving [them] the peaceful and permanent retirement they deserve.”32

Ham’s mistreatment by the Air Force inspired the creation of Save the Chimps, a state-of-the-art sanctuary in Florida that has provided a forever home for over 300 chimps since 1997, all rescued from private owners or descendants of the space chimp program. “They have bravely served our country,” said Dr. Carole Moon, the anthropologist who founded the sanctuary with the backing of Jane Goodall. “They are heroes and veterans.”33

Footnotes

- 1

Smithsonian’s National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute. “The History of Giant Pandas at the Smithsonian’s National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute.” https://nationalzoo.si.edu/animals/history-giant-pandas-zoo.

- 2

Kelly, John. “The Biography of Smokey Bear: The Cartoon Came First.” The Washington Post, April 25, 2010. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2010/04/24/AR2010042402441.html.

- 3

Colin Burgess and Chris Dubbs. Animals in Space: From Research Rockets to the Space Shuttle. Springer Science & Business Media, 2007.

- 4

Colin Burgess and Chris Dubbs. Animals in Space: From Research Rockets to the Space Shuttle. Springer Science & Business Media, 2007.

- 5

Nicholls, Henry. “Ham the astrochimp: hero or victim?” The Guardian, December 16, 2013, sec. Science. https://www.theguardian.com/science/animal-magic/2013/dec/16/ham-chimpanzee-hero-or-victim.

- 6

Loyd S. Swenson, Jr., James M. Grimwood, and Charles C. Alexander. This New Ocean: A History of Project Mercury. NASA History Series. National Aeronautics and Space Administration, 1966.

- 7

Smithsonian Institution. “Annual Report of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution 1963.” Digital Book. Annual Report of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian, 1963. Internet Archive. https://library.si.edu/digital-library/book/annualreportofbo1963smit.

- 8

Casey, Phil. “Astronaut Chimp Shuns Maggie, So Zoo’l Bring Lulu.” The Washington Post, Times Herald (1959-1973), April 29, 1964, sec. City Life. https://www.proquest.com/docview/142281958/abstract/C5F9F832C7F947B3PQ/1.

- 9

Casey, Phil. “Astronaut Chimp Shuns Maggie, So Zoo’l Bring Lulu.” The Washington Post, Times Herald (1959-1973), April 29, 1964, sec. City Life. https://www.proquest.com/docview/142281958/abstract/C5F9F832C7F947B3PQ/1.

- 10

Casey, Phil. “Astronaut Chimp Shuns Maggie, So Zoo’l Bring Lulu.” The Washington Post, Times Herald (1959-1973), April 29, 1964, sec. City Life. https://www.proquest.com/docview/142281958/abstract/C5F9F832C7F947B3PQ/1.

- 11

Henry Nicholls. “Celebrating Ham – Henry Nicholls.” Blog. Henry Nicholls (blog), January 31, 2011. https://henrynicholls.com/celebrating-ham/.

- 12

Colin Burgess and Chris Dubbs. Animals in Space: From Research Rockets to the Space Shuttle. Springer Science & Business Media, 2007.

- 13

Vicki Croke. The Modern Ark: The Story of Zoos: Past, Present & Future. Bard, 1998.

- 14

Friends of the National Zoo. “History - William Temple Hornaday - Visionary of the National Zoo,” n.d. https://web.archive.org/web/20080615142437/http://nationalzoo.si.edu/AboutUs/History/hornaday.cfm.

- 15

Smithsonian Institution Archives. “National Zoological Park,” April 14, 2011. https://siarchives.si.edu/history/national-zoological-park.

- 16

Vicki Croke. The Modern Ark: The Story of Zoos: Past, Present & Future. Bard, 1998.

- 17

Save the Chimps. “Ham, the First Chimpanzee in Space,” n.d. https://savethechimps.org/ham-space-chimp/.

- 18

Smithsonian Institution Archives. “Ham the Chimpanzee,” n.d. https://siarchives.si.edu/gsearch/ham%20the%20chimpanzee.

- 19

Henry Nicholls. “Celebrating Ham – Henry Nicholls.” Blog. Henry Nicholls (blog), January 31, 2011. https://henrynicholls.com/celebrating-ham/.

- 20

Colin Burgess and Chris Dubbs. Animals in Space: From Research Rockets to the Space Shuttle. Springer Science & Business Media, 2007.

- 21

Henry Nicholls. “The Way Of The Panda: Cameroon’s Gagarin: The Afterlife of Ham the Astrochimp.” The Way Of The Panda (blog), February 7, 2011. https://web.archive.org/web/20200801112111/http://thewayofthepanda.blogspot.com/2011/02/cameroons-gagarin-afterlife-of-ham.html.

- 22

Henry Nicholls. “The Way Of The Panda: Cameroon’s Gagarin: The Afterlife of Ham the Astrochimp.” The Way Of The Panda (blog), February 7, 2011. https://web.archive.org/web/20200801112111/http://thewayofthepanda.blogspot.com/2011/02/cameroons-gagarin-afterlife-of-ham.html.

- 23

Henry Nicholls. “The Way Of The Panda: Cameroon’s Gagarin: The Afterlife of Ham the Astrochimp.” The Way Of The Panda (blog), February 7, 2011. https://web.archive.org/web/20200801112111/http://thewayofthepanda.blogspot.com/2011/02/cameroons-gagarin-afterlife-of-ham.html.

- 24

Henry Nicholls. “The Way Of The Panda: Cameroon’s Gagarin: The Afterlife of Ham the Astrochimp.” The Way Of The Panda (blog), February 7, 2011. https://web.archive.org/web/20200801112111/http://thewayofthepanda.blogspot.com/2011/02/cameroons-gagarin-afterlife-of-ham.html.

- 25

Colin Burgess and Chris Dubbs. Animals in Space: From Research Rockets to the Space Shuttle. Springer Science & Business Media, 2007.

- 26

Henry Nicholls. “The Way Of The Panda: Cameroon’s Gagarin: The Afterlife of Ham the Astrochimp.” The Way Of The Panda (blog), February 7, 2011. https://web.archive.org/web/20200801112111/http://thewayofthepanda.blogspot.com/2011/02/cameroons-gagarin-afterlife-of-ham.html.

- 27

Nicholls, Henry. “Ham the Astrochimp: Hero or Victim?” The Guardian, December 16, 2013, sec. Science. https://www.theguardian.com/science/animal-magic/2013/dec/16/ham-chimpanzee-hero-or-victim.

- 28

Colin Burgess and Chris Dubbs. Animals in Space: From Research Rockets to the Space Shuttle. Springer Science & Business Media, 2007.

- 29

Friends of the National Zoo. “National Zoo Facts and Figures,” August 20, 2014. https://web.archive.org/web/20140820231633/http://nationalzoo.si.edu/Publications/PressMaterials/PressKit/FactsFigs.cfm.

- 30

The Right Stuff. Historical drama. Warner Bros., 1983.

- 31

Fly Me to the Moon. Romantic comedy drama. Columbia Pictures, 2024.

- 32

Colin Burgess and Chris Dubbs. Animals in Space: From Research Rockets to the Space Shuttle. Springer Science & Business Media, 2007.

- 33

Save the Chimps. “Ham, the First Chimpanzee in Space,” n.d. https://savethechimps.org/ham-space-chimp/.

>

>