"Right Out Our Front Door": The Construction of the Pentagon Destroyed a Black Neighborhood in Arlington

“I think the love and association of people is what kept people together. I sometimes thank the Lord that I was raised in that community.” - John Henderson, former resident of East Arlington [1]

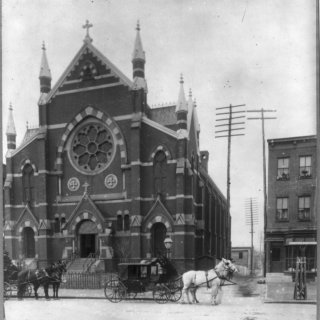

In the 1890s, Mount Olive Baptist Church had a problem. The federal government announced it would be closing Freedman’s Village, the encampment for freed slaves that had opened during the Civil War on the grounds of the old Arlington Estate. The church, which had served hundreds of African American families in the community since 1873, would be forced to find a new home for itself and its congregation. Looking just down the road, trustees found an available plot of land near the present-day location of the Pentagon. On August 12, 1892, Mt. Olive purchased two acres and sold lots to congregants. Twelve years later, a developer purchased an additional 27 acres and platted the land into lots for more African American families to move in.[2]

By 1940, over two hundred households and nine hundred people lived in the community, which became known as East Arlington and/or Queen City.[3] This community was a young and stable neighborhood, though not particularly wealthy. As former resident John Henderson recalled, residents took pride in what they created:

“A lot of [the homes] were built by local builders and a lot were built by the people themselves, the people who lived there.”[4]

Another woman who grew up in the neighborhood fondly recalled its sense of community. “We all knew each other, played together, walked to school together…People got along; they were much more together than they are now."[5]

East Arlington had a variety of businesses, a barbershop, and two Baptist churches, as well as its own trolley stop. Some residents lived in more comfort than others did, possessing larger homes with more space for family members or having grand wraparound screened porches.[6]

However, coming of age at the height of Jim Crow, East Arlington lagged behind white neighborhoods with regard to services. The streets lacked sidewalks, streetlights, curbs and gutters, and most homes lacked electricity. Arlington County never ran water or sewer pipes into the area, and so the homes lacked running water and flush toilets. Residents drew well water for washing, and had to fetch drinking water from a nearby spring.[7] As former resident, Eddie Corbin, recalled:

“There was a large pear tree right over the spring…When they were ripe, they would fall into the spring. They were the best pears you ever tasted."[8]

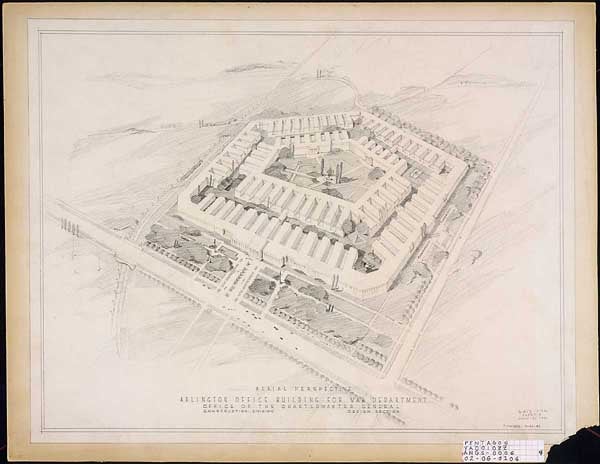

In the early 1940s, such pastoral scenes would evaporate almost overnight. As the War Department and the federal government mobilized in the run-up to the Second World War, it became apparent that the proper coordination of the American war effort would require the construction of a new military headquarters. The rapidly expanding War Department had outgrown its previous headquarters and was renting space in seventeen separate buildings across the District. It was clear that these conditions were expensive and inefficient, and that the building of a single nerve center would allow for the increased efficiency essential to winning the war.[9]

The Potomac River shoreline in Arlington quickly emerged as a viable site as the federal government already owned land upon which it could build this new military headquarters. The Department of Agriculture operated an Experimental Farm on the site, and the War Department owned a Quartermaster Depot site. Furthermore, with the opening of National Airport on June 16, 1941, Hoover Airport had been closed, thus providing more space for the project.[10]

The contract for the construction of the Pentagon was awarded on September 11, 1941, and a 24-hour construction project began the same day. After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the frantic pace increased even more. Residents of East Arlington watched the building’s rise with fascination and curiosity, unaware their neighborhood was in danger.[11]

As former resident George Vollin, who was quoted in the Washington Star several decades later, described it:

We just thought they were going to build a building over in the field, but we had no idea it was going to be as big as it was. Then they came to building the roads, and that’s when they took all the houses.[12]

Indeed, while the Pentagon structure had been built with minimal impacts on East Arlington, the written plans for the project required razing the community in order to build roads and parking areas for the 35,000 war workers that would occupy the building.[13] Tragically, this fact was not shared with the residents until the last possible moment – a detail that troubled few of the planners, apparently.

Jay Downer, a highway consultant on the project, even went so far as to frame the displacement of the African American neighborhoods as a benefit, and described it as such in frankly racist terms. As he told the National Capital Planning Commission in October 1941, the new road network “takes out some troublesome darkey slave cabins” and “cleans up that strip.”[14]

Construction was to begin around East Arlington on January 19, 1942. However, the War Department waited until early February to give notice to the area families that the property was being seized by eminent domain and they would have to vacate their homes by March 1. One resident, Gertrude Jeffress, later testified to the confusion and frustration of community members upon receiving this crushing news, “It was a predicament. Where in the world were we going to find a place to live?”[15]

As another former resident recalled:

They started work before we moved…. They started by putting the sewers in. They came right up 8th Street and they dug a trench there. They started it before we got out of there. And that was a pretty deep hole, and that hole ran from where the Pentagon is now up to Fort Myer. They weren’t kidding around because it was right out our front door.[16]

For the over two hundred families living in East Arlington, finding housing in less than thirty days was close to impossible. Washington was overwhelmed by the flood of war workers arriving to seek government positions, and housing for both blacks and whites was in short supply. Families sought housing with friends and relatives, and were often forced to leave furniture and other belongings behind.[17]

Community residents sought help from whomever they felt would be sympathetic to their cause as well as powerful enough to intervene on their behalf. They hired a lawyer who wrote a letter to First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, appealing for her aid, protesting the short notice they had been given, and expressing frustration with the paltry sum that the government intended to pay for their homes.[18]

Roosevelt forwarded the missive to the House Military Affairs Committee, which held a hearing on the subject on February 13. The chief of the roads bureau showed no regret for the decision and cited military necessity, saying that the construction was “a matter of split-second timing” and that “any delay would be very serious.”[19]

Following the hearing, the War Department continued in its plan to level East Arlington, although it did decide to offer temporary housing in trailers for those residents who could not find shelter. By early April 1942, the last residents of East Arlington had left the area and moved into army trailers located in two nearby neighborhoods.

Eddie Corbin recalled the separations caused by the removal of residents into these trailer cities:

Everyone who lived there was really separated. Some went to one area and some went to the other…Uncle Sam put up trailers on Johnson’s Hill and put up trailers in Green Valley…The trailer city was there for another four years. People were put in what was called two-bedroom trailers.[20]

The War Department burned East Arlington to the ground on April 17, 1942. The federal government compensated 180 property owners $369,427, or about $2,052 per owner. Those 128 East Arlington households who had rented their homes received no compensation.[21]

In 2013, Historian Nancy Perry conducted oral history interviews with several surviving residents of East Arlington who grieved the loss of their community. As one put it, “Some of those people you never did see them again. …They never came back to this area. When East Arlington got leveled, that really broke that community up.” In the words of another: “We lost our community; we lost our homes; we lost our work. What was lost will never be replaced.”[22]

Footnotes

- ^ https://library.arlingtonva.us/2011/10/26/memories-of-queen-city/

- ^ Nancy Perry (2015) Eminent domain destroys a community: leveling East Arlington to make way for the Pentagon, Urban Geography, 37:1, 141-161, DOI: 10.1080/02723638.2015.1100953

- ^ As detailed above, development happened in two waves. The original two-acre plot that was purchased by Mt. Olive Baptist Church is generally labeled “Queen City.” The second, larger, plot is generally referred to “East Arlington.” However, given the developments’ proximity to one another, and the fact that both shared the same fate due to the Pentagon project, many historians lump the two subdivisions together and use either “Queen City” or “East Arlington” to refer to the whole African American community, which settled in this area. In this article, we will do the same and use “East Arlington” to refer to the entire community.

- ^ https://library.arlingtonva.us/2011/10/26/memories-of-queen-city/

- ^ Nancy Perry (2015) Eminent domain destroys a community: leveling East Arlington to make way for the Pentagon, Urban Geography, 37:1, 141-161, DOI: 10.1080/02723638.2015.1100953

- ^ Nancy Perry (2015) Eminent domain destroys a community: leveling East Arlington to make way for the Pentagon, Urban Geography, 37:1, 141-161, DOI: 10.1080/02723638.2015.1100953

- ^ Nancy Perry (2015) Eminent domain destroys a community: leveling East Arlington to make way for the Pentagon, Urban Geography, 37:1, 141-161, DOI: 10.1080/02723638.2015.1100953

- ^ https://library.arlingtonva.us/2011/10/26/memories-of-queen-city/

- ^ https://arlingtonhistoricalsociety.org/the-destruction-of-east-arlington/

- ^ https://arlingtonhistoricalsociety.org/the-destruction-of-east-arlington/

- ^ Nancy Perry (2015) Eminent domain destroys a community: leveling East Arlington to make way for the Pentagon, Urban Geography, 37:1, 141-161, DOI: 10.1080/02723638.2015.1100953

- ^ Kast, S. (1975, September 1). Not everyone thought it was so dreamy. Washington Star, pp. B1, B3.

- ^ https://library.arlingtonva.us/2011/10/26/memories-of-queen-city/

- ^ https://books.google.com/books?id=Dr0UIZJw58YC&printsec=frontcover&sour…

- ^ https://books.google.com/books?id=Dr0UIZJw58YC&printsec=frontcover&sour…

- ^ Nancy Perry (2015) Eminent domain destroys a community: leveling East Arlington to make way for the Pentagon, Urban Geography, 37:1, 141-161, DOI: 10.1080/02723638.2015.1100953 Interview with Vincion, July 2013.

- ^ Nancy Perry (2015) Eminent domain destroys a community: leveling East Arlington to make way for the Pentagon, Urban Geography, 37:1, 141-161, DOI: 10.1080/02723638.2015.1100953

- ^ https://books.google.com/books?id=Dr0UIZJw58YC&printsec=frontcover&sour…

- ^ https://books.google.com/books?id=Dr0UIZJw58YC&printsec=frontcover&sour…

- ^ https://library.arlingtonva.us/2011/10/26/memories-of-queen-city/

- ^ Nancy Perry (2015) Eminent domain destroys a community: leveling East Arlington to make way for the Pentagon, Urban Geography, 37:1, 141-161, DOI: 10.1080/02723638.2015.1100953

- ^ Nancy Perry (2015) Eminent domain destroys a community: leveling East Arlington to make way for the Pentagon, Urban Geography, 37:1, 141-161, DOI: 10.1080/02723638.2015.1100953 Interview with Vincion, July 2013.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)