Razing the Mother Church: The Sale and Destruction of Saint Augustine Catholic Church

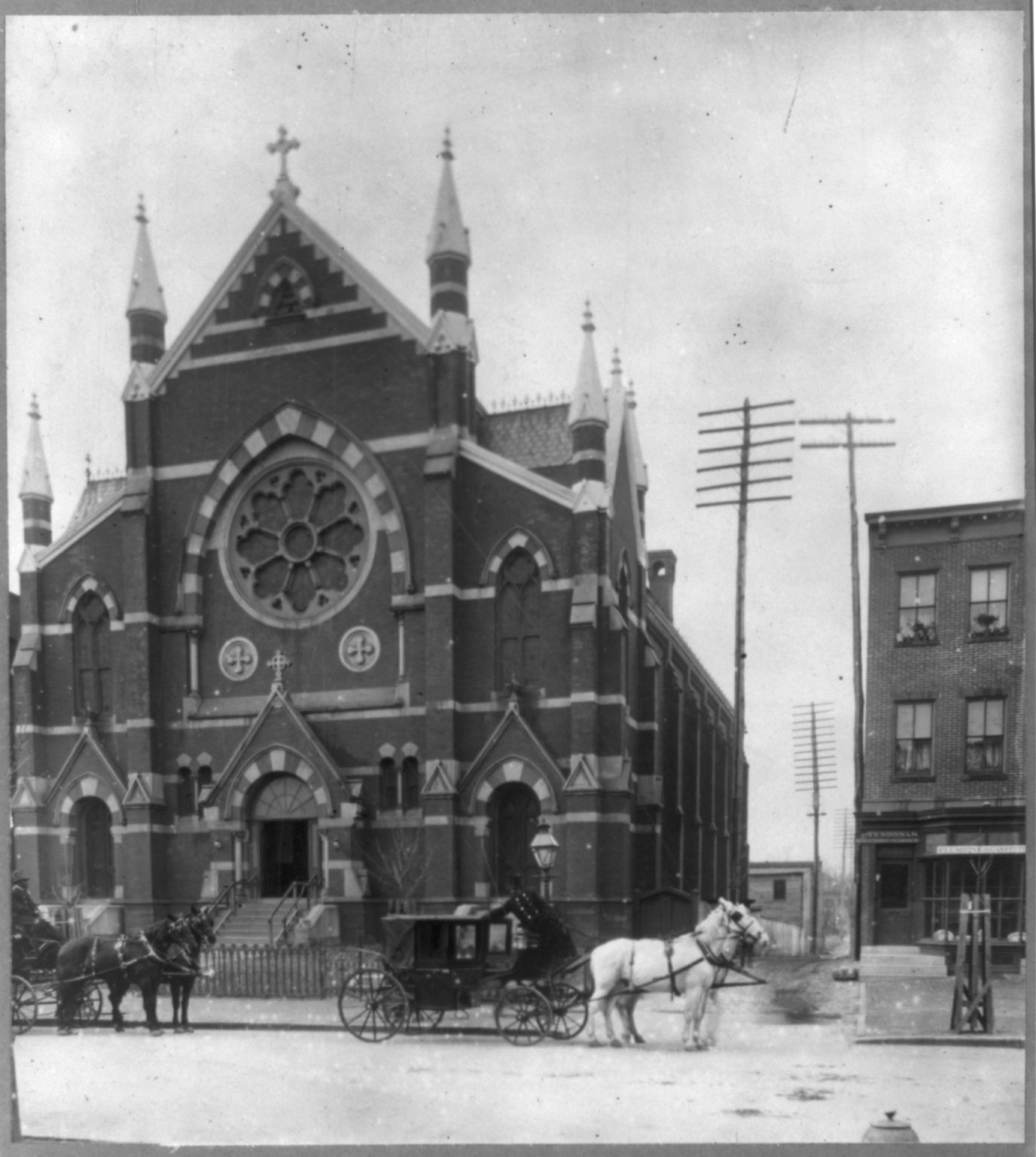

In 1946, two attorneys finalized their purchase of a historic church building in the heart of Washington.[1] For seventy years, Saint Augustine Catholic Church at 15th and L was the place where the Black Catholics of the District were baptized, educated, given communion, and buried. In two years, it would be rubble.

At its founding in 1858, the church then known as Blessed Martin de Porres established the first school for Black children in the District of Columbia.[2] Operating out of the basement of St. Matthew’s Cathedral, the free Black Catholics of Martin de Porres sought to create a church of their own that would meet the needs of the Black community and grant them the dignity that was afforded to their white counterparts.[3] Although Black parishioners were allowed to worship in the existing Catholic churches, their presence was often barely tolerated. Black parishioners were forced to sit in the worst pews at the rear of the church.[4] They were not allowed to take Communion, one of the most sacred tenets of Catholic life, until every white parishioner had finished.[5] The faithful of Blessed Martin de Porres, longed for a true church of their own where they could practice their faith with dignity.

On June 27, 1864, a Black Catholic businessman by the name of Gabriel Coakley made an appointment with Abraham Lincoln.[6] A cabinetmaker whose wife worked as a seamstress in the White House, Coakley was the leader of a committee assembled to fundraise the construction of a new church building for the Blessed Martin de Porres congregation.[7] The committee’s plan was to secure the President’s permission to host a festival on the White House lawn to raise funds for their new church. According to D I. Murphy, the former American consul-general to Bulgaria who personally met Coakley during his time working at St. Augustine in 1885, the President almost immediately agreed, telling them that “Certainly you have my permission. Go over to General French’s [the Commissioner of Public Buildings and Grounds] and tell him so.”[8] On July 4th, 1864, the President and his wife personally attended the festival, helping the parishioners raise more than $1,200 dollars for their new church.[9] Further costs were covered by the parishioners, who carried out the excavation and the construction of the site themselves.[10] In 1876, the new church at 15th and L St. NW was dedicated to St. Augustine, the great African philosopher and theologian – a church built by the faithful to care for some of the most disadvantaged followers of the Catholic faith.[11]

Almost immediately the new church began to grow. Due to its proximity to the large Catholic populations in southern Maryland, Washington attracted a growing body of Black Catholics, with St. Augustine growing to a population of more than three thousand at the turn of the century.[12] By 1905, St. Augustine was the largest Black Catholic church in the nation and had developed the reputation as the “Mother Church” of Black Catholics. [13] A glowing Washington Post article that spring described how its renowned choir had made the church “a mecca for lovers of sacred music,” and described St. Augustine as a meeting point where white Catholics could “kneel beside their colored brethren at the communion rail.”[14]

Such an optimistic appraisal of the racial politics of the Catholic Church belies the deep institutional hostility facing the faithful of St. Augustine. For most of its history, the church was a Black community under the authority of an overwhelmingly white institutional hierarchy. Some within the leadership of the American Catholic Church were sympathetic to the injustices experienced by their Black followers including Archbishop John Ireland of St. Paul, Minnesota who declared that “No Church is a fit temple of God where a man, because of his color, is excluded or made to occupy a corner,” during a visiting sermon at St. Augustine in 1890.[15] However, such declarations of support often made little difference in the everyday lives of Black Catholics. Even the sacred space of St. Augustine was not fully their own. For over a century – from its founding until the appointment of Rev. Russell L. Dillard in 1991 – St. Augustine was a Black parish lead by white pastors.[16]

Furthermore, outside of the Mother Church, parishioners often faced discrimination and segregation from their fellow Catholics. In a footnote to his doctoral thesis on St. Augustine, scholar John P. Muffler describes the personal experiences of his family in Washington:

My mother and grandmother remember witnessing this practice [the segregation of Communion] as late as the 1940s. My grandmother also recalls an incident during that time when the pastor of St. Paul’s Church told the Black Catholics present to get out of his church and go down the street to St. Augustine’s “where you belong.” The incident remains a bitter memory to the older members of St. Augustine’s.[17]

While white Catholics may have been free to worship where they wished, St. Augustine was the only spiritual shelter for the thousands of Black men and women who prayed within its walls.

The painful dichotomy of became a focal point for Black Catholics in their struggle against systemic racism in the nation and the Catholic Church itself. Dr. Thomas Wyatt Turner, one of the parishioners of St. Augustine and a charter member of the NAACP, became one of the strongest voices for reform in the interwar period.[18] In 1919, Turner responded to a letter from the president of the white-only St. Mary’s Seminary in Baltimore with a fiery denunciation, stating:

If all the white priests and laymen decide that segregating and discriminating Catholics are reasonable in the Catholic Church we shall cling to the undefiled Banner of the Lord even though we may have to tread the ‘wine press alone’.[19]

In 1924, Turner founded the Federated Colored Catholics of the United States, which sought to combat racism in Catholic education and the church as a whole.[20] St. Augustine stood at the center of the organization’s early growth, hosting the body’s first two national conventions in 1925 and 1926.[21] The Mother Church’s pastor, Rev. Alonzo J. Olds, was an ally of the organization, becoming its “spiritual director” and delivering an address at its 1928 convention.[22] Although the Federated Colored Catholics dissolved in 1933, it played a key role in bringing race to the forefront of Catholic discussion and laying the groundwork for the Catholic civil rights movements of the 1960s.[23]

In the backdrop of Dr. Turner’s push for racial reform within the Catholic Church, the Mother Church entered a period of calamitious decline. In 1924, Father Olds purchased an additional plot of land near the Church in the hope of constructing a new building that would house the church’s school and social hall.[24] At the time, the purchase seemed reasonable given the parish’s growing population and relatively strong financial position and it was approved by Olds’ superior in the church, Archbishop of Baltimore Michael Curley.[25] However, by the time the school was completed in November 1929, the church’s financial position was far more dire. Two months after the stock market crash, the church now faced the seemingly impossible challenge of paying off the hundreds of thousands of dollars of debt it had incurred in the purchase and construction of the new site.[26]

The situation only worsened as the Great Depression wore on. Though the crisis impacted the nation at large, African Americans were particularly hard hit. The District’s Black community found themselves largely deprived of work and excluded from the recovery brought about by the New Deal.[27] With many of its followers struggling to make ends meet, St. Augustine saw a sharp decline in attendance and collections, falling from a population of 2,500 followers in 1930 to 1,698 the following year.[28] By 1932, the church was largely unable to meet its interest payments, forcing it to take on significant loans from corporate interests and other parishes within the Catholic Church.[29] At the peak of the crisis, Archbishop Curley ordered Father Olds to beg the Riggs National Bank for a refinancing of their mortgage, telling him that “If the Bank is not willing to facilitate our refinancing at a mere nominal rate of interest, and without pressure in the future, then the only thing we can do is to turn over what property we have to the Bank for public sale.”[30] While Father Olds was successful in renegotiating their contract, the relief was temporary at best. It was clear to the Archdiocese that any permanent solution would include the sale of the old church.[31]

Throughout the financial woes of the 1930s, a powerful disconnect emerged between the leadership of St. Augustine and the men and women who made it their spiritual home. As the Archdiocese began to court potential buyers for the church building, members of the parish were not told of the plans to sell the church, nor were they given details of the transaction that would take place.[32] In 1864, the followers of Blessed Martin de Porres went to the President of the United States to raise money for a church that they built by hand; nearly seventy years later, their descendents were not even consulted regarding its destruction. It is impossible to know whether the faithful of St. Augustine would have been able to accomplish a similarly Herculanean feat to save the Mother Church. What is certain is that they were never given the chance.

On January 17, 1946, the Mother Church was sold for $300,000.[33] Four days later, the Evening Star ran an article revealing that the transaction was conducted between Monsignor Joseph Nelligan, chancellor of the Archdiocese of Baltimore and Washington, and attorneys Spencer Gordon and Fontaine C. Bradley who were working on behalf of a secret third party.[34] The article ascribes the transaction with a degree of mundane intrigue, claiming that even Msgr. Nellison “said he did not know the name of the principal.”[35] However, both Gordon and Bradley were partners at the firm Covington & Burling and both represented a shared client: The Washington Post.[36]

The next two years were a flurry of activity. The school building that had been purchased by Father (now Msgr.) Olds was hastily renovated in order to become the new location for St. Augustine Catholic Church.[37] Behind-the-scenes, the transition from the original building to the new location was fraught with constant disagreement between contractors, the parish, and the archdiocese.[38] At one point, Msgr. Olds was forced to beg the Washington Post for an extension on the mandated vacation of the priests from the premises; the request was rejected.[39] Finally, after two years of frantic negotiations and constant upheaval, the church was torn down on January 22, 1948.[40]

On January 23rd, 1948, the Washington Post ran a short article under the headline “Church Aided by Lincoln Being Razed.” It began:

A church that Abraham Lincoln helped establish here was being torn down yesterday. St Augustine’s Catholic Church at 15th and L St. nw—its Gothic Spires reaching 60 feet into the sky since the 1870s—soon will be a pile of rubble. And after that, perhaps a parking lot.[41]

The rest of the article detailed St. Augustine’s history and included a note that the building had been “sold to two Washington lawyers” two years earlier.

Notably absent was any mention of the newspaper itself. An oversight? Perhaps, though it seems more likely the Post sought to distance itself – at least in the short term – from the dismantling of the old church building, which had meant so much to so many. Of course, that would be only temporary. Plans for the Post’s new seven-story printing building on the site would be announced the following year.[42]

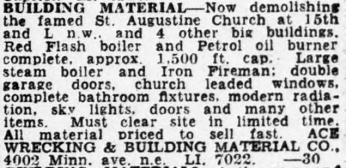

In the meantime, parishioners from St. Augustine had to watch as their beloved house of worship was torn down and, literally, sold for scrap. The day before the destruction began, Ace Wrecking and Building Material Company placed an ad in the Evening Star offering raw materials taken from “the demolition of the famous St. Augustine Church.”[43] Two days later, the advertisement would be expanded with this lurid description of the materials scavenged from the building:

Building Material – Now Demolishing the famed St. Augustine Church at 15th and L n.w. and 4 other big buildings. Red flash boiler and Petrol oil burner complete. approx., 1500 ft cap. Large steam boiler and Iron Fireman: double garage doors, church leaded windows, complete bathroom fixtures, modern radiation, skylights, doors and many other items. Must clear site in limited time. All material priced to sell fast.[44]

For many in the Mother Church, the sale and demolition deeply tainted their relationship with white Catholic leadership. Even forty years after the sale, Muffler noted that “most of the older members of the parish admit that they feel betrayed” and that “they are reluctant to trust archdiocesan officials, including their archbishop.”[45] These attitudes were on display in the summer of 1984 as the congregation prepared to celebrate the church’s 126th anniversary. Mayor Marion Barry’s administration proclaimed June 17 St. Augustine’s Day in the District, and the planned celebration featured a Gospel Mass and the unveiling of a plaque at the Washington Post building -- a monument of labor and faith that once stood on the same grounds.[46] For many of the older parishioners, the event was a reminder of a deeply painful moment in their history. Pauline Jones, a lifelong Catholic and worshipper at St. Augustine, told a Post reporter, “There are several older people who said they can't bear to come down to the unveiling of the plaque this Sunday because they said it's just too sad for them.”[47]

Others, however, saw the event as another step in the resilient history of the Mother Church. As 84-year-old Beatrice Stewart, put it. "The church is always doing something and I like that, I don't get sad about the past… I just look forward to what it will be doing next.”[48] For more than one hundred and twenty years, the faithful of St. Augustine Catholic Church outlasted slavery, segregation, the Great Depression, and the hostility of their own church. The old church building was torn to the ground, but the Mother Church survived.

Author’s Note: This article would not have been possible without the invaluable research done by John P. Muffler in his 1989 doctoral dissertation, “This Far By Faith: A History of St. Augustine’s, The Mother Church for Black Catholics in the Nation’s Capital.”

Footnotes

- ^ “St. Augustine’s Church Sold for $300,000 to Two Attorneys”, Evening Star (Washington, DC), Jan. 21, 1946.

- ^ Virginia Mansfield, “First Black Catholic Parish In D.C. Marks a Milestone”, Washington Post (Washington, DC), June 16, 1984.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ John Paul Muffler, “This Far By Faith: A History of St. Augustine’s, the Mother Church for Black Catholics in the Nation’s Capital” (doctoral dissertation, Columbia University, 1989), 14.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Catholic News Agency, “Why Abraham Lincoln held a White House fundraiser for this black Catholic Parish,” Catholic Sentinel (Portland, OR), Feb. 13, 2020.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ D.I. Murphy, “Lincoln, Foe of Bigotry”, America, Feb. 11, 1928, quoted in Muffler, “This Far By Faith”, 21-22; “History of the US and Bulgaria”, U.S. Embassy in Bulgaria, accessed Feb. 11, 2020, https://bg.usembassy.gov/our-relationship/policy-history/io/.

- ^ Muffler, “This Far By Faith”, 24.

- ^ Mansfield, “First Black Catholic Parish”.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Cyprian Davis, The History of Black Catholics in the United States (New York: Crossroad Publishing Company, 1990), 110; “Largest Catholic Church”.

- ^ Largest Colored Catholic Church in United States”, Washington Post (Washington, DC), May 28, 1905; Agnes Kane Callum, “St. Augustine: A Mother Church for Black Catholics,” Catholic Review, Archdiocese of Baltimore, Jan. 19, 2012, https://www.archbalt.org/st-augustine-a-mother-church-for-black-catholi….

- ^ “Largest Colored Catholic Church”.

- ^ Joseph Butsch, “Catholics and the Negro,” The Journal of Negro History 2, no. 4 (Oct., 1817), 409.

- ^ Laura Sessions Stepp, “St. Augustine’s Gets 1st Black Pastor”, Washington Post (Washington, DC), Jan. 26, 1991.

- ^ Muffler, “This Far By Faith”, 31.

- ^ Marilyn W. Nickels, “Thomas Wyatt Turner and the Federated Colored Catholics”, U.S. Catholic Historian 7 no. 2/3 (1988), 219; Ibid., 218

- ^ Ibid., 223.

- ^ Ibid., 226.

- ^ Muffler, “This Far By Faith”, 122

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Nickels, “Thomas Wyatt Turner”, 230; Davis, “History of Black Catholics”, 229.

- ^ Muffler, “This Far By Faith”, 125.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid., 125-126.

- ^ Ibid., 110-111.

- ^ Ibid., 110-111.

- ^ Ibid., 130; Ibid., 133.

- ^ Ibid., 135.

- ^ Ibid., 134.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid., 138

- ^ “St. Augustine’s Church Sold for $300,000 to Two Attorneys”, Evening Star (Washington, DC), Jan. 21, 1946.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “Spencer Gordon, Noted Lawyer and Civic Figure, Dead at 63”, Washington Post (Washington, DC), Sep. 13, 1950; “Fontaine C. Bradley Dies”, Washington Post (Washington, D.C.), Apr. 24, 1991.

- ^ Muffler, “This Far By Faith”, 139.

- ^ Ibid., 140.

- ^ Ibid., 142.

- ^ “Church Aided by Lincoln Being Razed”, Washington Post (Washington, DC), Jan. 23, 1948.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “Church Aided by Lincoln Being Razed”, Washington Post (Washington, DC), Jan. 23, 1948.

- ^ Building Material”, Evening Star (Washington, DC), Jan. 21, 1948

- ^ “Building Material”, Evening Star (Washington, DC), Jan. 25, 1948.

- ^ Muffler, “This Far By Faith”, 139.

- ^ Mansfield, “First Black Catholic Parish”.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

![This integrated classroom at Anacostia High School is the culmination of a seven year struggle against DC's segregated school system. [Source: LOC] Integrated classroom at Anacostia High School](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/AHS%20Class_0.jpg?itok=GNxSJFox)

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)