The Dedication of the Lincoln Memorial

“Thus a pathetic handful of the fast dwindling survivors of the Civil War, some of whom knew Lincoln, had the satisfaction of witnessing within their lifetime the dedication of a marble symbol of Stanton’s announcement that the Great Emancipator belongs to the ages. Grand Army men, led by Lewis S. Pilcer, Commander-in-Chief, presented the colors and laid symbols of the army and navy at the foot of the structure, Across the aisle sat gray-clad confederate veterans, and from their seats they could look over the Potomac to the Virginia Hills, where Arlington, once the home of Robert E. Lee, nestles among the trees.”[1]

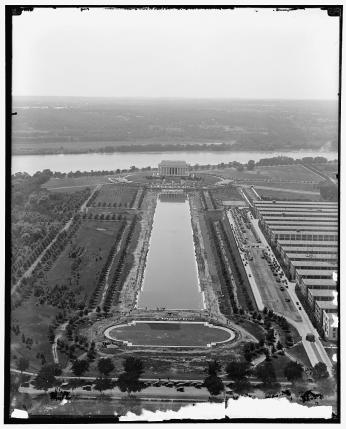

This was how The New York Times described the scene on May 30, 1922, when the Lincoln Memorial was dedicated. It was a grand event and thousands of Washingtonians and others, including Civil War veterans on both sides, converged upon the Mall for the ceremony. With a touch of poetic license, The Baltimore Sun described the size of the excited crowd.

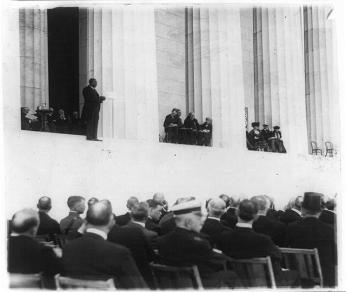

“The swelling tide of humble people who stood for hours under a blazing sun to claim this temple of freedom and the man whose memory it enshrines as their own. Far as the eye could reach from the high base of the memorial, Americans were spread over the lawns and clustering under the trees that grace the setting. How many may have been there to hear the words of the speakers, caught up and flung to far distances by the amplifiers that studded the coping atop the marble structure, no man might estimate.”[2]

Viewers could have arrived at the dedication ceremonies by utilizing the latest new technology, the automobile. Planners of the dedication ceremony now had to consider how several thousand cars could be guided and parked throughout the nearby area to arrive at and leave from the dedication ceremony. Metropolitan police claimed that their efforts had successfully prevented any traffic difficulties and avoided the kind of massive traffic jam that had occurred a few months earlier on the day of the burial of the unknown soldier at Arlington National Cemetery.[3]

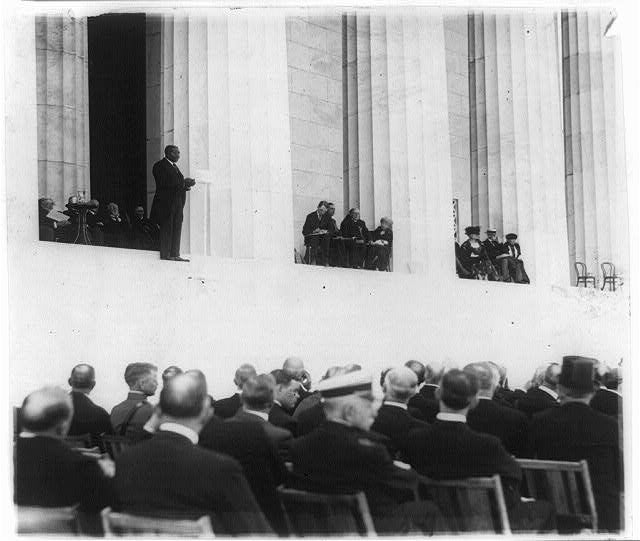

The proceedings began with an invocation by Reverend Wallace Radcliffe of the New York Presbyterian Church, followed by a speech by Robert Russa Moton, the day’s only African American speaker. Following Moton, poet Edwin Markham read aloud his poem, “Lincoln, The Man of the People.” Former President William H. Taft then gave a speech presenting the memorial to Harding, who also delivered a speech celebrating the monumental achievement. The ceremony then ended with a benediction by Reverend Radcliffe, who concluded the dedication by consecrating the new memorial.

Audience members heard the speeches from a distance with the help of microphones and loudspeakers that carried the words of the day’s chosen speakers. The U.S. Navy also broadcast the ceremony across two of its local radio networks.[4]

The day prior to the dedication, The Washington Post crowed that two million people would be able to hear the dedicatory ceremony with these new technologies, saying “Amplifying devices, cleverly concealed so that they did not detract from the beauty of the memorial, carried the speakers’ voices several hundred yards, and by the same means the speeches were sent broadcast by radiophone.”[5]

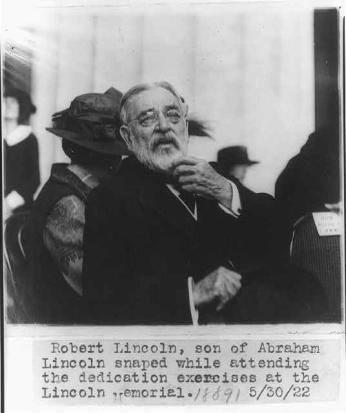

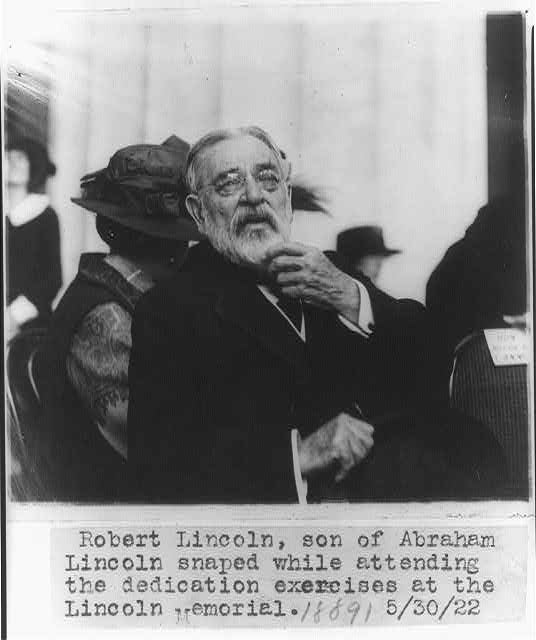

However, perhaps the most important guest of all was 79-year-old, Robert Todd Lincoln, the only surviving son of the sixteenth president. Making what turned out to be his last public appearance, the younger Lincoln’s pale and aged visage reminded members of the audience of his father, martyred in the final days of the Civil War at nearby Ford’s Theatre.

During the Civil War, Robert had served in the US Army under Ulysses S. Grant and then gone on to a successful career in law and business. He had also served as Secretary of War under Presidents James Garfield and Chester Arthur before becoming the Minister to Great Britain under President Benjamin Harrison. He would die in 1926 and was buried in Arlington National Cemetery.[11]

The throngs in attendance for the dedication would have noticed another aspect of the event, though in Washington of the 1920s it was so ordinary that most probably would not have remarked upon it: There was strictly segregated seating at the ceremony. African American attendees were forcibly directed to a colored section of the stands by a marine who was noted for his roughness. When the marine was later questioned regarding his behavior, he reportedly replied, “That’s the only way you can handle these damned ‘niggers.’”[12]

The African American speaker at the event also confronted marginalization during and after the ceremony, although he was allowed to give a speech that contrasted with those of Taft and Harding. Robert Russa Moton was a race leader chosen by the Commission to give the first speech at the dedication of the Lincoln Memorial. Moton had been carefully chosen, as he was an “accommodationist” who had advised Wilson and Harding on the subject of race relations. Moton had succeeded Booker T. Washington as the principal of Tuskegee Institute in 1915, and he agreed with Washington that economic uplift rather than racial equality should be the focus of African American efforts.[13]

While the white organizers of the dedication had carefully selected Moton, the speech that he initially submitted to the Lincoln Memorial Commission was deemed too radical. Moton had hoped to position Lincoln as part of the larger narrative of African American struggle against discrimination, and to raise a call for racial justice in the United States. Instead, the Commission forced him to give a more mild speech, yet one where he still questioned the extent of American racial progress since 1865.

Mainstream white newspapers would largely dismiss Moton’s speech, reporting on it only sparsely and often inaccurately. The Washington Post did not speak of Moton by name when they wrote of “A representative of the race for which the Great Emancipator did so much likewise lifted his voice in gratitude for the freedom of so many in American from serfdom.” Another article from the Post reported the speech as if it had been a triumphant and unqualified assertion of American racial progress under the headline, “Freedom to Negro Justified, He Says.”[14]

Airplanes were permitted to fly over the memorial before and after the dedication in order to take birds-eye-view photographs, but a no-fly zone was imposed during the proceedings. One commercial pilot, however, mistook the timing of the ceremony, and flew over the memorial as the President was speaking, causing horrible noise and briefly drowning out Harding’s speech.[15]

The guffaw helped spur new airspace restrictions over the District.[16]

Despite the technical difficulties, the dedication of the Lincoln Memorial was an event that confirmed the monument’s place as a beloved part of the new National Mall and affirmed the place of the sixteenth president in the memory of the nation. In a myriad of ways, the scene outside the new marble structure reminded Americans of both how far they had come since the Civil War and how far society still had to go.

Footnotes

- ^ Harding Dedicates Lincoln Memorial; Blue and Gray Join. May 30, 1922. The New York Times

- ^ People Render Their Homage at Lincoln Shrine: Thousands Endure Blazing Sun To Witness Memorial Dedication. May 31, 1922. The Baltimore Sun.

- ^ NO MISHAPS MARK DAY'S CEREMONIES. (1922, May 31). The Washington Post (1877-1922)

- ^ The Lincoln Memorial and American Life. 155.

- ^ 2,000,000 TO HEAR LINCOLN ADDRESSES: Great Amplifier and Navy Radio Will Be Used at Dedication Rites Tomorrow. HARDING PRINCIPAL SPEAKER Vice President Coolidge Among Others-Final Plans Completed, Chairman Graves Announces. All Can See and Hear. Among Greatest Occasions. The Washington Post. May 29, 1922.

- ^ https://www.nps.gov/linc/learn/historyculture/lincoln-memorial-importan…

- ^ Harding Dedicates Lincoln Memorial; Blue and Gray Join. May 30, 1922. The New York Times.

- ^ Harding Dedicates Lincoln Memorial; Blue and Gray Join. May 30, 1922. The New York Times.

- ^ https://www.nps.gov/linc/learn/historyculture/evolution-of-lincoln-memo…

- ^ Hugh Brewster, Gilded Lives, Fatal Voyage: The Titanic’s First Class Passengers and their World, 7-8. Crown Publishers, New York. 2012.

- ^ https://www.nps.gov/linc/learn/historyculture/lincoln-memorial-important-individuals.htm

- ^ The Lincoln Memorial and American Life. 157.

- ^ The Lincoln Memorial and American Life. 155.

- ^ The Lincoln Memorial and American Life. 158.

- ^ The Lincoln Memorial and American Life. 155.

- ^ Capital's Commissioners Rule Against Low-Flying Airships: Humming Motors Which Interrupted Harding And Are Held Responsible--Violators Will Be Fined If They Are Caught. The Baltimore Sun. July 20, 1922.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)