Metro: It's Not Easy Being Green

December 28, 1991 marked an important milestone for the Metro and for Washington. As Metro workers handed out green "Welcome Aboard!" balloons, D.C.'s Congressional delegate Eleanor Holmes Norton addressed a crowd in front of the new Anacostia Metrorail station.

"This subway is not magic, but it can be catalytic.... a new Anacostia will rise in part on the backs of the cars that will bring prosperity across that river."[1]

For those huddled in the freezing temperatures, the day was a long time coming. Though the dashed green line (Metro's designation for a future line) had been included on system maps for years, the project faced countless setbacks due to budgeting, route disputes, and construction methods. But now — finally — the promises were coming true as the Anacostia, Navy Yard and Waterfront stations opened their fare gates.

Following 10 years of research on transportation in the greater Washington area, and the 1967 creation of the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority (WMATA), on March 1, 1968, the WMATA Board officially approved a 97.2 mile rail system which would service D.C., and surrounding areas of Virginia and Maryland.[2] This plan created the five original Metrorail lines: Blue, Orange, Red, Yellow, and Green. The first portion of the Red Line opened on March 27, 1976, with the Blue, Orange, and Yellow following suit over the next seven years. By 1984, however, the only line that was left completely untouched was Green—and hopes for its construction were not looking promising. With a proposed route from Prince George’s County through the core of the city, the Green Line promised to invigorate some lower income areas of Maryland and D.C.[3] The project would bring high-quality transportation to Anacostia for the first time, as well as help restore the Shaw and Cardozo neighborhoods in the aftermath of the 1968 riots.

From the time the line was drawn on the original 1968 plans, however, its route was disputed. While long-time residents of the areas in question felt the need for the Metro line was well overdue, they expressed significant concerns over the day-to-day disruptions and permanent displacements that the new transit line would force upon them if it was routed in certain directions. In a 1980 interview, Jackson Graham, Metro’s first general manager, explained:

“Every time we would go to a public hearing, some strong-willed matriarch would stand up and say, ‘You can’t come up this street,’ and we knew it wouldn’t go up that street. So we’d draw another line, and hold another hearing.” [4]

This arduous process of rerouting mainly affected the portion of the Green Line between present day U-Street and College Park, and resulted in the creation of the Fort Totten and West Hyattsville stations, as the route was shifted slightly eastward from Chillum to avoid demolishing too many residential areas.[5]

Although the Green Line was included on the original Metro plan, routing disputes spanned over several years, and the construction schedule followed “the path of least resistance,” meaning that the lines with comparatively less controversy—Red, Blue, Orange, and Yellow—were built first, pushing Green further down the list.[6]

These construction pushbacks seemed to suggest that the Green Line was on the verge of extinction, which only infuriated “neighborhood activists, politicians, and government officials” more, as they argued that the Green Line “should have been the first built because it would serve the most disadvantaged sections in the Washington area.”[7]

As construction work on the first four lines progressed through 1980, a new contract was needed in order for work to continue after June of 1981. Larry Saban, regional representative of the Maryland Department of Transportation, was concerned about the uncertainty of the Green Line, and refused to sign the new contract until there was assurance from his D.C. and Northern Virginia counterparts that there would still be economic support when the Green Line was to be built. This move threatened the completion of the rest of the unfinished Metro system, causing conversations—and controversy—about the Green Line to increase rapidly.

In 1980, the cost of the Green line was estimated at $2 billion with a predicted completion set in 1990.[8] This plan was again threatened, however, by two main issues. First, in Prince George’s County, a decision to change the entire end of the train route would force the removal of homes and threaten a historical area.

Second, in the Fort Totten neighborhood of D.C., citizens requested that a planned elevated section of the train be, instead, placed in a tunnel. This request was in line with a promise that former D.C. transportation director Douglas Schneider had made to Fort Totten residents at a public hearing two years earlier. However, by 1980, officials were asking for “flexibility,” as they faced a much different fiscal reality than they had previously envisioned.[9] Adding a tunnel would increase the Green Line’s cost by at least $100,000, and was also opposed by the federal Urban Mass Transportation Administration which provided 80% of the money for building the Metro system.[10]

The District government shared citizens’ uncertainty that the Green Line would ever become a reality, and at a meeting in December 1980, it threatened to withhold funding for the project until the Metro Board created a construction schedule more favorable to the Green Line—according to the Washington Post, this “incident was only the latest example of snafus and politicking that [had] slowed [the line’s] construction.”[11]

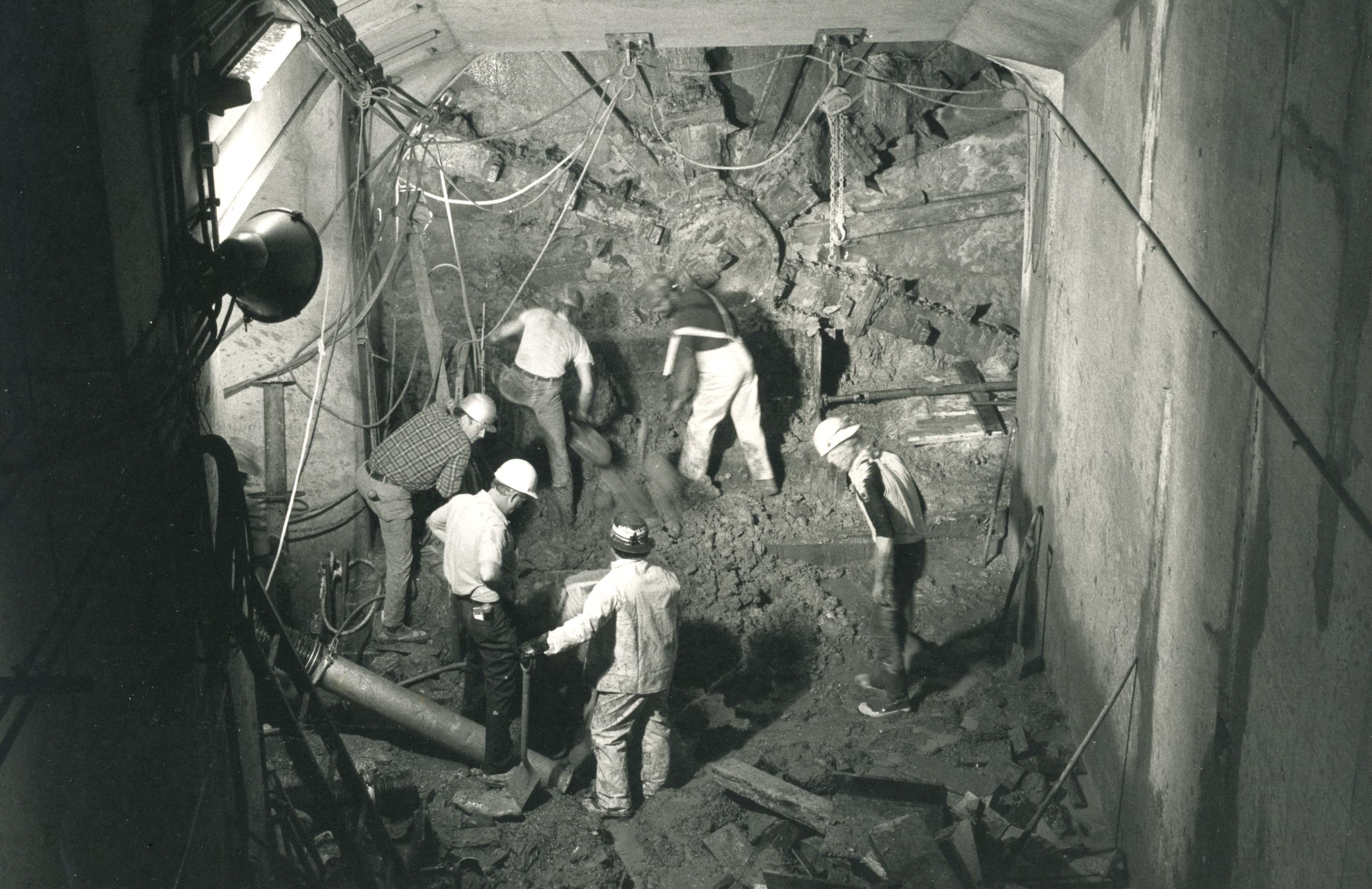

On May 23, 1985, the Metro Board adopted a plan to raise the cost of the project to $147.1 million, and place the section of rail between Fort Totten and Avondale in a tunnel, thereby settling the most controversial and disputed issue.[12] With this decision ending the “last major battle over the Green Line’s route,” construction finally began.[13]

Though residents began to see tangible progress—in the form of backhoes and other heavy machinery ripping up streets—the project continued to face financial setbacks through the 1980s, including the Reagan Administration’s withholding of a congressionally appropriated $392 million.[14]

Still, construction continued until May 11, 1990 when the line met yet another hiccup. Metro fired contractor Mergentime/Perini Joint Venture due to the contractor’s breach of contract resulting in significant schedule delay, reduction in manpower, and unsafe conditions that they had been previously warned about.[15]

This latest delay had business owners in Shaw outraged, as they struggled to keep business going with the streets completely torn apart. Speaking to the Washington Post in 1990, Jamal Muhammad, manager of Talib’s Discount Clothing, claimed he had already lost 75% of his business since 7th Street NW had closed for tunneling, and worried that the new delay “is going to devastate us.”[16] Edward Archie, owner of nearby Tuxedo Valet, called the construction slowdown “a blow after many blows.”[17] In fact, Ben’s Chili Bowl on U Street would end up being one of the only businesses in the neighborhood to survive the devastation of both the 1968 riots and the Green Line construction.

Anxious to avoid further public frustration and finish the already 80% completed Shaw and U Street Stations, Metro hired Perini, which had separated from Mergentime, as the new contractor on May 25.

It would take another year but the Shaw and U Street stations, along with the Mount Vernon Square station, finally opened on May 11, 1991—exactly one year after the contractor firing. Several hundred people lined the streets in Shaw to watch marching bands parade down the newly paved road, momentarily forgetting the abandoned businesses behind them. Combined with the expansion of the system into Anacostia seven months later, it marked a new era for public transit in Washington. For customers in Washington's inner city, 20 years of waiting for a train that seemed like it would never come were finally over.

Epilogue: The Green Line was completed in phases over the next 10 years. The stretch from Fort Totten to Greenbelt opened on December 11, 1993, and the connecting section between U-Street and Fort Totten opened September 18, 1999. The last five stations between Anacostia and Branch Avenue opened for business January 13, 2001.

For a year-by-year look at Metro’s evolution, check out this map animation: https://ggwash.org/view/67044/happy-birthday-metro-watch-metros-evolution-since-1976-in-this-slideshow

Footnotes

- ^ Tousignant, Marylou, "After Feuds, Amid Fanfare, Metro Rolls Into Anacostia," The Washington Post, December 29, 1991, B1.

- ^ “Metro_history.pdf.” Accessed June 10, 2018. https://www.wmata.com/about/upload/history.pdf.

- ^ Feaver, Douglas B. 1980. “What Ever Happened to the Green Line?” The Washington Post (1974-Current File); Washington, D.C., October 14, 1980, sec. METRO Federal Diary/Obituaries/Classified. https://search-proquest-com.library.access.arlingtonva.us/hnpwashington….

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ The Washington Post, Times Herald (1959-1973); Washington, D.C. 1968. “Metro to Have Eight Major Routes in District, Suburbs” March 2, 1968, sec. City Life. https://search-proquest-com.library.access.arlingtonva.us/hnpwashington….

- ^ Feaver, Douglas B. 1980. “What Ever Happened to the Green Line?” The Washington Post (1974-Current File); Washington, D.C., October 14, 1980, sec. METRO Federal Diary/Obituaries/Classified. https://search-proquest-com.library.access.arlingtonva.us/hnpwashington….

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ McQueen, Michel McQueen. 1981. “Green Line Progress.” The Washington Post (1974-Current File); Washington, D.C., January 29, 1981, sec. THE DISTRICT WEEKLY. https://search-proquest-com.library.access.arlingtonva.us/hnpwashington….

- ^ Lynton, Stephen J. 1985. “Tunnels Set for Disputed Section of Green Line: Section of Green Line Will Go Underground.” The Washington Post (1974-Current File); Washington, D.C., May 24, 1985, sec. METRO FEDERAL DIARY. https://search-proquest-com.library.access.arlingtonva.us/hnpwashington….

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Lynton, Stephen J. 1986. “Metro Approves 3-Phase Plan To Build Green Line by 1990s: Green Line Plan Approved.” The Washington Post (1974-Current File); Washington, D.C., May 23, 1986, sec. METRO FEDERAL DIARY. https://search-proquest-com.library.access.arlingtonva.us/hnpwashington….

- ^ Henderson, Nell. 1990. “Metro Fires Contractor Over Delay: Green Line Opening Put Off Until Spring.” The Washington Post (1974-Current File); Washington, D.C., May 12, 1990, sec. Metro. https://search-proquest-com.library.access.arlingtonva.us/hnpwashington….

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

![Ben's Chili Bowl, 1980 (Photo Source: Library of Congress) Highsmith, Carol M, photographer. Ben's Chili Bowl, Washington, D.C. United States Washington D.C, None. [Between 1980 and 2006] Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2011635251/. (Accessed December 04, 2017.) Ben's Chili Bowl, 1980 (Photo Source: Library of Congress) Highsmith, Carol M, photographer. Ben's Chili Bowl, Washington, D.C. United States Washington D.C, None. [Between 1980 and 2006] Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2011635251/. (Accessed December 04, 2017.)](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/17058v.jpg?itok=egZM-IR9)

![“The restored Lincoln Theatre, once a premier African-American entertainment venue, Washington, D.C.” (Photo Source: The Library of Congress) Highsmith, Carol M, photographer. The restored Lincoln Theatre, once a premier African-American entertainment venue, Washington, D.C. United States Washington D.C, None. [Between 1980 and 2006] Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2011636050/. “The restored Lincoln Theatre, once a premier African-American entertainment venue, Washington, D.C.” (Photo Source: The Library of Congress) Highsmith, Carol M, photographer. The restored Lincoln Theatre, once a premier African-American entertainment venue, Washington, D.C. United States Washington D.C, None. [Between 1980 and 2006] Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2011636050/.](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/17856v.jpg?itok=KiWAaHRq)

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)