The Willis Conover Questions

During World War II, the place to be in Washington, D.C. was the Stage Door Canteen. Located in Lafayette Square’s old Belasco Theater, the wildly popular night spot offered “free entertainment, food and smokes for uniformed members of the United States armed forces, stationed in, or passing through, Washington.”[1] One young man, who’d been stationed at Fort Meade, recalled the women who volunteered to dance there. “Of course you were not allowed to take them out afterwards, one of them told me as I took her out afterwards.”[2]

Cheekiness aside, this young serviceman took quite a serious interest in dancing at the canteen. Or, rather, in the music to which patrons danced. One evening, a popular orchestral tune played over the loudspeaker. “Fine in its place,” he explained, “but not for dancing. So I went around backstage and asked the volunteer stage manager if she’d mind if I pick a few records?” She would not, and neither would everyone else in the canteen. Tommy Dorsey’s “Boogie-Woogie” and Charlie Barnet’s “Cherokee” got everyone on their feet and grooving.[3]

As it turned out, the stage manager was quite impressed with the young man’s intuition. “My husband is the manager of WWDC and he’s coming around to pick me up in a little while,” she disclosed with an invitation: “Would you like to meet him?” He certainly would, and the meeting yielded a second invitation: “How would you like to work when you’re not on duty?”[4] Merrily, he would, and the young man set off to become a global icon in jazz radio. The man, of course, was none other than Willis Conover.

But, wait… who was Willis Conover?

Don’t worry, the New York Times had the same question in 1959, when jazz critic John S. Wilson published a profile under the headline “Who is Conover? Only We Ask.” By means of an anecdote, Wilson shed light on a man who was internationally famous but (at the time) largely anonymous at home.

While visiting Moscow, a group of American tourists had encountered a flurry of questions from curious Russians, “what was the price of an American automobile, what did Americans think of ‘beat generation’ writers, how many Americans were unemployed?” When the interrogation broached the subject of music, one American boasted familiarity with Shostakovich, Khachaturian, and Prokofiev. “And,” one Russian chimed in, “is Willis Conover highly regarded in the United States?”[5]

Russian eyes widened, American brows furrowed, and a puzzled silence ensued.[6]

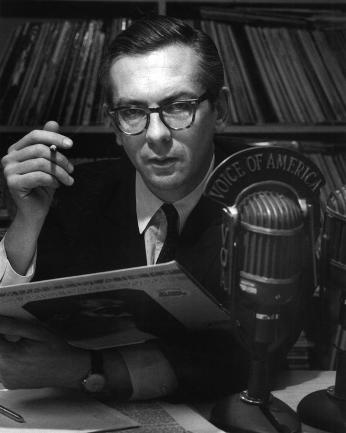

If only to hinder further embarrassment overseas, Wilson set out to unshroud this enigmatic personality. “Willis Conover,” he made plain, was not “a subtle invention of the Kremlin designed to bedevil visiting Americans. He is a completely authentic citizen of the United States, based in Washington, D.C., whose nightly two-hour radio program on the Voice of America, ‘Music U.S.A.,’ has made his voice and name familiar not only in Moscow but in practically every corner of the world except the United States.”[7]

Conover’s exclusion of American listeners was not a matter of personal preference. Voice of America was – and still is – a government-sponsored international radio service. Since its establishment during WWII, it was prohibited from disseminating content within the U.S.[8] VOA broadcasts – everything from Willis Conover’s “Music U.S.A.” to reporting on foreign policy – were to be “directed solely to external audiences.”[9] The reason for the policy – which wasn’t lifted until 2013 – was simple: VOA was intended to promote American interests abroad and lawmakers worried that broadcasting inside the United States would amount to domestic propaganda. There were no such concerns with broadcasting to international audiences, however, and Congress found radio to be of great use against antagonistic Soviet airwaves during the Cold War.[10]

After mastering his talent for jazz programming at WWDC, Willis Conover joined Voice of America in 1955. By the time of Wilson’s article four years later, the self-described “program conductor” had amassed an estimated audience of 30 million jazz-lovers in 80 countries around the globe.[11] He was especially popular in Eastern Europe.

Behind the Iron Curtain, jazz was a “forbidden Western art,” a Washington Post writer explained, some years after his first visit to the Soviet Union. “I found myself late one night in the apartment of a jazz fan whose thirst for music had pushed him into dissident status. After midnight…he pulled down the shades, turned the TV up to a painful blare, and then switched on his radio, which he furtively tuned to the Voice of America. Soon, we were listening to the great Willis Conover, for decades the radio ambassador of jazz on the U.S. government’s shortwave station.”[12]

Conover’s two-hour program, “Music U.S.A.,” was split evenly between pop and jazz. The more-popular Jazz Hour opened with Duke Ellington’s sprightly tune, “Take the ‘A’ Train,” and as it gently faded out, Conover’s mellifluous voice came through – a “sonorous, meticulous basso”[13] with the announcement: “Time for jazz. Willis Conover in Washington, D.C., with the Voice of America Jazz Hour.”

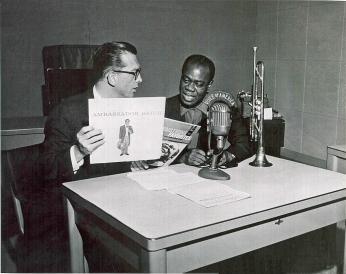

The show went beyond entertainment, according to Conover: “It says we’re a nation with social mobility. It says we’re creative. It says a lot about the diversity of America.”[14] His claims went ever further: “Jazz corrects the fiction that America is racist. Minorities have a tough time everywhere but the acceptance and success of so many Negro musicians and singers in jazz in the United States makes it obvious that someone like Louis Armstrong, for instance, is not an exception.”[15]

Conover was particularly attentive to the jazz fever in Eastern Europe because of what the improvisational music represented. “Jazz is a cross between total discipline and anarchy…. It’s a musical reflection of the way things happen in America. We’re not apt to recognize this over here but people in other countries can feel this element of freedom.

“They love jazz because they love freedom.”[16]

Some Washingtonians, however, were soon “apt to recognize” a few discrepancies between Conover’s inclusive portraits of American music and his activities in the local Washington jazz scene.

On the basis of his work with Voice of America, Conover began to collect a number of official positions representing jazz. He chaired the White House Library Commission and was President Richard Nixon’s unofficial adviser on jazz; he also served on the State Department’s jazz subcommittee for cultural presentations and consulted for National Endowment for the Arts. In 1971 Conover was brought on as the jazz consultant for the newly-established Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts.[17]

As he told the Evening Star during the fall of that year, Conover hoped to elevate the artistry of jazz “to its deserved place of prominence as ‘America’s classical music’.”[18]

The new national cultural center was scheduled to open its doors to the public in September 1971. Conover was quick to ensure jazz was included in the inaugural performance season and fashioned a three-day affair titled “The 1971 House of Sounds Festival.” Newspaper advertisements promised an impressive lineup of performers including Count Basie, Muddy Waters, Buddy Rich and Roberta Flack. Beneath the program read:

“WILLIS CONOVER

Producer and Narrator”[19]

But as the program began to take shape, the Center’s jazz advisory panel grew concerned that Conover had followed a narrow and biased selection process.[20] While there were some preeminent performers, most of the festival was centered around student and professional big band acts. Furthermore, Conover decided not to name the festival with the term “jazz” claiming that “many musicians consider the term jazz restrictive and that it may alienate people who dislike jazz of a particular era – modern.”[21]

The panel grew increasingly frustrated, wondering if Conover was the right person for the job. A few days before the festival opened, Washington Post writer Hollie West asked point-blank: “Should Willis Conover Stay?” There were several facets of Conover’s role to be considered: his race, tastes, intent and his blind (and deaf) spots.[22]

Many were troubled by the sight of a singular white jazz promoter and spokesperson to multiple federal institutions. Calling Conover “almost the czar of resources for jazz on a federal level” panel member and former jazz bassist Julian Euell spelled out his concerns to West: “My major objection to Willis Conover is not personal. But I think it’s poor judgement to have a white guy in that job. It’s following the old pattern of whites controlling and making the profits from the music.”[23]

Further disturbing was Conover’s persistent favoritism towards big band music – a subgenre of jazz largely outdated by the early 1970s – and rejection of contemporary jazz movements. According to Euell, by pushing student big band acts that were mostly white, Conover ignored the “young black cats” and more accomplished African American jazz players – many of whom were struggling professionally and could use the increased publicity the festival would provide.[24]

Conover, in turn, stressed that “color should have nothing to do with it – only ability,” and argued that he had proven his abilities as an organizer. He eagerly cited that he had “worked for years to interest the government in support of [jazz] and its musicians.” However, claiming to be sympathetic to “their anger and their frustration,” Conover said he welcomed “qualified blacks” to his field of work.[25]

The counterargument did little to quell the controversy. Citing his mishandling of the Kennedy Center’s prestige, Hollie West called for Conover’s resignation from the position of jazz consultant less than a week before the festival.[26] He refused, but the hoe-hum reviews of the festival couldn’t have left Conover feeling confident.

Hollie West dispensed few accolades,[27] likening the festival to “a creaky vessel drifting into harbor [rather] than a christening of jazz at a new culture center.” Naming no names, he resolved, “the Kennedy Center can do better.”[28]

His remark was actually quite tame when put up against Larry Barrett’s unadulterated Evening Star assessment, titled with a solemn R.I.P. “Most of the capacity audience was already safely out,” Barrett assured, “before a great piece of schlock was dropped on a virtually defenseless jazz festival which had labored through a weekend of five concerts and more than 20 hours of blowing, bowing, and banging.”[29]

Headliner Muddy Waters “did what Muddy always does; white kids rejoiced, clapped on the beat and gave a standing ovation. Then,” (and Barrett named names), “came Conover’s cacophonous conclusion.” He illustrated:

“Impresario Willis Conover had all the stars of the show – and some who hadn’t even been in it – walk out of the stage, single file, and join in a Giant Monster Jam Session. All-purpose trumpeter Clark Terry had sounded ‘Boots and Saddles’ and 30 or more good-natured horsies lined up for a silly and demeaning closing. It was one piece of available nuttiness I had thought could not happen (what with all those other high school halftime routines unexploited).”[30]

Although the festival had concluded, the “Conover Question” still begged an answer. West noted it odd that the Kennedy Center, “a complex that purports to be a cultural showcase for the country,” had not a single black member in its management team despite the fact that “blacks have had such a large hand in creating a large part of this country’s culture.” Additionally, he questioned why a single man – Conover – should be “able to control jobs and money for musicians, influence taste on a national scale and affect the future of the music in a comprehensive way.” Conover’s “self-serving [and] unstinting devotion” was not a strong enough credential to deem him a jazz authority.[31]

“We need people at the Kennedy Center who are genuine authorities on American music, people who are dedicated to preserving the past and planning for the future. There are many candidates for such positions, irrespective of race. I am not saying that only blacks should be considered, but I am appealing for fairer treatment of blacks, for attention to the idea that blacks can be managers as well as performing artists.”[32]

Larry Barrett continued his meditations, too, with a nod to Conover:

“Remove all disk jockeys from positions of control or influence….For an all-night audience of radio fans they may be exactly right; for a concert audience, they are completely wrong. And they are constantly introducing artists who, they are certain to aver, ‘need no introduction’.”[33]

The disk-jockey-turned-jazz-consultant reiterated that he came into these positions of control “because no one else had thought of performing such functions. But,” he admitted, “we all should work to open new avenues for both blacks and whites. The field should be expanded, not cut by my resigning.”[34]

As it turned out, the writing was on the wall. In early November, Conover tried his hand at a New-Orleans-themed jazz festival and, in doing so, brought to Larry Barret’s mind the “universal question: If a thing isn’t worth doing in the first place, is it worth doing badly?”[35] Soon after, Conover left his position as jazz consultant at the Kennedy Center.

His departure did not result in immediate improvements to the jazz programming. By the Kennedy Center’s first birthday, the jazz advisory panel had nearly collapsed and, with Conover gone, the status of jazz at the Center was “in limbo.”[36] The Center’s 12-day contemporary music festival in September 1972 included neither jazz nor rock music. It was a surprising omission. As Hollie West reminded his readers, jazz and rock were “musical styles that have captured the imagination of most of the Western world in the last 25 years.”[37]

Fortunately, the story didn’t end there. Jazz presentation at the Kennedy Center would flourish in future years, particularly under the leadership of Dr. Billy Taylor, who was appointed as the Center’s artistic adviser for jazz in 1994. Taylor, himself a pianist, composer, scholar and broadcaster, steered the Center towards a more inclusive and spirited treatment of jazz until his death in 2010.[38]

Conover might have eventually come to understand his own Kennedy Center ordeal as but a brief mishap. During and after his short tenure there, he’d continued broadcasting “Music U.S.A.” with unquestioning passion and without pause until 1996 when he died of lung cancer.[39]

The life of Willis Conover, it may appear, was riddled with questions. Some were straightforward, and others indicated larger critical interrogations taking place in the field of jazz. John S. Wilson brought to America’s attention a question that, if they couldn’t answer, might be embarrassing to ask overseas: Who is Conover? Hollie West later updated the Conover Question, inviting his readers to consider, Should Conover have this much power over the jazz scene? To denounce Conover was to urge that the Kennedy Center embrace its opportunity to employ a diverse and well-versed cohort of jazz authorities. When Larry Barrett jumped in, he questioned what business a radio disc jockey had producing live concerts.

The question now remains, What is the legacy of Willis Conover? The answer is as obvious to some as it is irrelevant to others. His legacy is both a celebrated one and an absent one.

One thing that few can question is Conover’s passion and his faith in the power of jazz. The persistent conviction he brought to Voice of America created a ubiquitous legacy which takes the form of countless jazz musicians’ origin stories. As Jazzletter founder Gene Lees put it, “Time and time again, when you ask a jazz player from the erstwhile Iron Curtain countries how he became interested in jazz, you’ll hear a variant on ‘Well, I heard Willis Conover’s program and…’”[40]

Dr. Taylor spoke at a jazz awards ceremony in St. Petersburg in 1998. The Willis Conover Awards, as it was named, gave the new Kennedy Center advisor an opportunity to put his own spin on the Conover Question from years past. “In his programs he pointed out that jazz was not only played by African Americans, but by people from many places around the world…. He made [this point] so very clearly that many people in Russia said, ‘I can do that. And I can express something which is unique to me as a Russian,’ using jazz to make their say.”[41]

P. S.

After Conover’s death, some devoted fans of this “unsung hero” also credited him with ending the Cold War and bringing down the Soviet Union. But when both Presidents George H. W. Bush and Bill Clinton dismissed campaigns to award Conover the Presidential Medal of Freedom, Gene Lees grew “haunted by the refusal of his nation to give him his due.” The collection of Conover’s broadcasts were a “national treasure of inconceivable value,”[42] and he “did more to crumble the Berlin wall and bring about collapse of the Soviet Empire than all the Cold War presidents put together.”[43]

The most plausible explanation for the “nation’s ingratitude,” Lees speculated, was suspicion from the CIA. “Did some paranoid spook wonder what was his magical connection to the Russian people? And is there somewhere in some CIA or FBI file a notation questioning his loyalty?"[44] But…perhaps not every Conover Question finds an audience prepared to answer.

Footnotes

- ^ "Capital At Last Assured A Stage Door Canteen." The Washington Post. July 27, 1942, 10.

- ^ Stokes, W. Royal. "If the World's Jazz Players Speak Poor English, It's Your Fault." The Washington Post, September 16, 1984, B3.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Wilson, John S. "Who Is Conover? Only We Ask." The New York Times, September 13, 1959, SM64.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Snow, Nancy. "The Smith-Mundt Act of 1948." Peace Review; Abingdon Vol. 10 Iss. 4, December 1998, 619-624.

- ^ “Past VOA Directors: Charles Thayer (1948-1949)” Voice of America, Jul 18 2018. https://www.insidevoa.com/a/4488436.html

- ^ “History: VOA Through the Years” Voice of America. Apr 3, 2017. https://www.insidevoa.com/a/3794247.html

- ^ Wilson, John S. "Who Is Conover? Only We Ask." The New York Times, September 13, 1959, SM64.

- ^ Fisher, Marc. "Freedom In the Air." The Washington Post, April 12, 1998, L9.

- ^ “Obituaries: Willis Conover Dies at 75; Voice of America’s Jazz Host.” The Washington Post, May 19, 1996, B6.

- ^ Steward, Tom. “How ‘Voice’ Reaches Its 43-Million Audience.” The Evening Star, October 15, 1967, 47.

- ^ Wilson, John S. "Who Is Conover? Only We Ask." The New York Times, September 13, 1959, SM64.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ West, Hollie. “Clarifying the Conover Question.” The Washington Post, Oct 10, 1971, L2.

- ^ Dobson, Gwen. “Non-Playing Mr. Jazz: World Is His Audience.” The Evening Star, Sept 24, 1971, E1.

- ^ Display Ad 233 “The 1971 House of Sounds Festival” The Washington Post, Aug 29, 1971, G7.

- ^ West, Hollie. “Jazz Discord: Issue in Black and White: Jazz Consultant Discord: Should Willis Conover Stay?” The Washington Post, Sep 19, 1971, G1.

- ^ West, Hollie. “Big Bands.” The Washington Post, Sep 14, 1971, B8.

- ^ West, Hollie. “Jazz Discord: Issue in Black and White: Jazz Consultant Discord: Should Willis Conover Stay?” The Washington Post, Sep 19, 1971, G1.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Dobson, Gwen. “Non-Playing Mr. Jazz: World Is His Audience.” The Evening Star, Sept 24, 1971, E1.

- ^ West, Hollie. “Black Music: Paled in the White Tradition.” The Washington Post, Sept 19, 1971, G2.

- ^ West, Hollie. “Count Basie’s Bash.” The Washington Post, Sep 25, 1971, B7.

- ^ West, Hollie. “‘House of Sounds’.” The Washington Post, Sep 27, 1971, B1.

- ^ Barrett, Larry. “R.I.P. (and About Time) for ‘House of Sounds’.” The Evening Star, Sep 27, 1971, B6.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ West, Hollie. “Clarifying the Conover Question.” The Washington Post, Oct 10, 1971, L2.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Barrett, Larry. “Jazz in an Alien Setting: Let’s Try to Make the Best of It.” The Evening Star, Oct 10, 1971, J10.

- ^ Delaney, Paul. “Conover, Voice of Jazz, Is Challenged as a ‘Czar’.” New York Times, Oct 18, 1971, 48.

- ^ Barrett, Larry. “A Surreal Jazzfest of Little Note.” The Evening Star, Nov 8, 1971, 24.

- ^ West, Hollie. “Festival: No Rock, No Jazz.” The Washington Post, Sep 7, 1972, D1.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Schudel, Matt. “Billy Taylor, revered musician, broadcaster and spokesman for jazz, dies at 89.” Dec 30, 2010, http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2010/12/29/AR20101…

- ^ Thomas, Robert McG, Jr. “Willis Conover Is Dead at 75; Aimed Jazz at the Soviet Bloc” The New York Times, May 19, 1996, 35.

- ^ Lees, Gene. “In Memoriam: Willis Conover.” Jazzletter Vol. 21 No. 1, Jan 2002.

- ^ Chernov, Sergey. “Russian Jazz Lovers Pay Tribute To Voice of America Radio Host.” The Moscow Times, Jun 18, 1998, http://old.themoscowtimes.com/sitemap/free/1998/6/article/russian-jazz-…

- ^ Lees, Gene. “In Memoriam: Willis Conover.” Jazzletter Vol. 21 No. 1, Jan 2002.

- ^ Lees, Gene. “A word for Willis.” Jazzletter Vol. 12 No. 5, May 1993.

- ^ Lees, Gene. “In Memoriam: Willis Conover.” Jazzletter Vol. 21 No. 1, Jan 2002.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)