The Washington Post Celebrates Young Authors With One of the Most Famous Pieces of Music in History

“Around the world and back again the name of The Washington Post has been carried to the rhythmic beat of countless millions of marching men. The rolling drum has awakened the silences of the remotest corners of the earth with the echoes of its fame.”

The Washington Post, December 6, 1927

On a beautiful June day in 1889, adorned with a “fresh breeze and occasional light clouds to temper the sun’s heat,” 25,000 people covered nearly six acres of the Smithsonian grounds for a glorious awards ceremony.[1] Of these 25,000 people, at least 22,000 of them were children, who ranged in age from small toddler to last year of high school, and were the first members of the new Washington Post Amateur Authors’ Association.[2]

This Association, started by The Washington Post itself, was meant to encourage students to further excel in their studies—especially English composition.[3] The incentive to join the Association? The opportunity to enter the essay writing competition for the chance to win a stunning solid gold medal. June 15, 1889 was the day that those shiny medals were to be handed out to the eleven student winners—one from each grade level of the D.C. public schools.

The Washington Post Amateur Authors’ Association awards ceremony, held right out in front of the National Museum, was quite the sight to see. The Post remarked:

“Never before were so many children seen together in one gathering. Not even on ‘egg-rolling’ day, when the hill sides of the White [House] lot are covered with young ones, was there ever such a swarm of boys and girls, almost full grown, half grown, and just begun to grow, as congregated on the Smithsonian grounds.” [4]

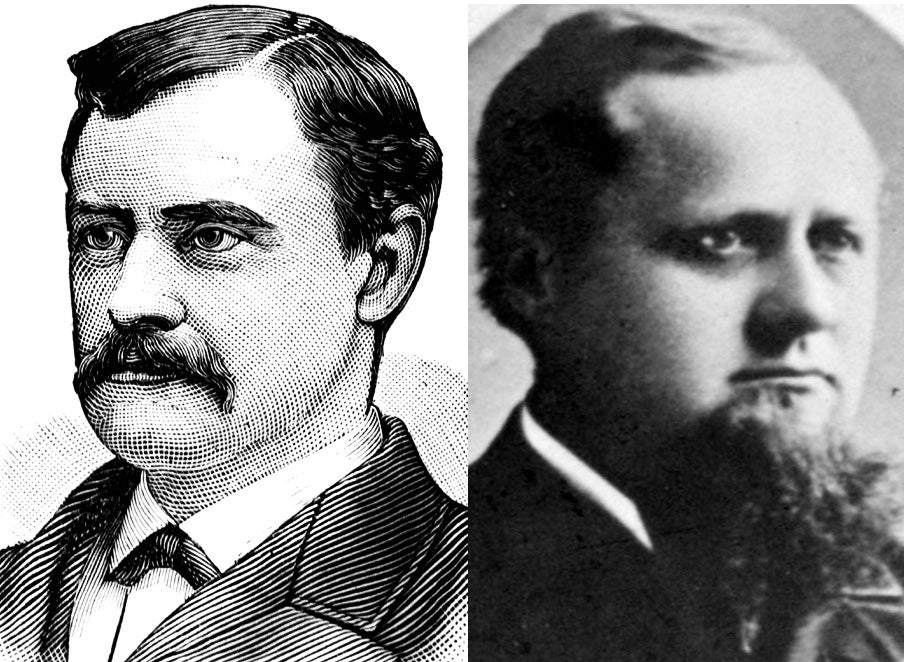

The audience members surrounding the acre of land around the presentation platform were “packed like sardines,” and the platform itself held chairs for all of the distinguished guests, prize recipients, judges, and the Marine Band.[5] Distinguished guests at the event included Superintendent W.B. Powell representing the D.C. public schools, owner of The Washington Post, Beriah Wilkins, Willis B. Hawkins, President of the Amateur Authors’ Association, and Supreme Court Justice Samuel Freeman Miller to present the medals. President Benjamin Harrison was expected to be at the event, but was not able to make it, as he had accepted a trip down the river on the Postmaster General’s yacht. He did however send his private secretary, Mr. Halford, and the Superintendent of Public Buildings and Grounds, Col. John M. Wilson in his place.[6]

At promptly 4 p.m., the Marine Band started to play, marking the beginning of the ceremony. In Hawkins’s opening remarks, he noted with excitement, that eight of the eleven contest winners were girls, and that he believed that girls being intellectually ahead meant good things for the future.[7] Following Hawkins, Powell and Miller both made speeches expressing the importance of acquiring and furthering education, and how this essay writing competition played a role in those goals.[8] Afterward, Miller presented the medals. These solid gold medals, hand-crafted by local jewelers Messrs. M. W. Galt, Bro. & Co., each featured unique designs and had custom engravings for each winner.

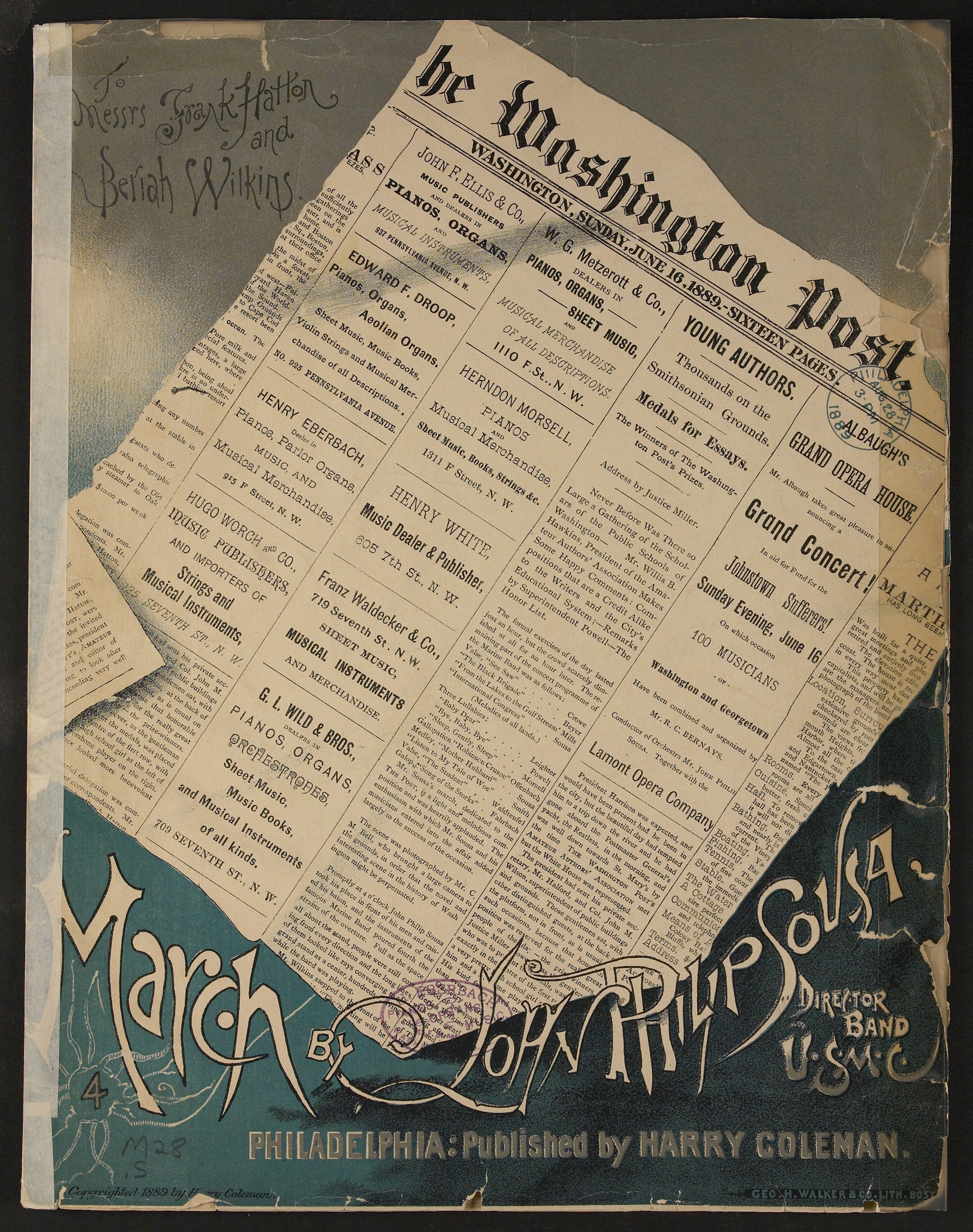

Although it might seem like these handsome gold medals would be the main highlight of this event, the jewelry actually wasn’t the only gem to come out of the ceremony…it just so happens that the 25,000 people present at the Smithsonian grounds were also witnesses to the premiere of what would become one of the most famous pieces of music in history.

Months before the ceremony was to take place, General Frank Hatton, an owner of The Washington Post, ran into Washington native and beloved Marine Band conductor, John Philip Sousa. Sousa wrote of the encounter:

“One morning in 1889 I met Gen. Frank Hatton, one of the proprietors of The Washington Post, on the street, and he told me that a contest they were having for the best essays among the public school children had assumed such great proportions that they had requested the Government to give them Smithsonian grounds as the place to confer prizes on the successful ones, and he said, or course, it would be a great thing if The Post could have the Marine Band. I suggested that he request the Secretary of the Navy to order the band to appear and give a concert during the ceremonies, and we received an order from the Secretary to that effect. A few days later I met Gen. Hatton and Beriah Wilkins, another owner of The Post, and they confirmed the order of the Secretary that I would appear, and one of them said it would be a great think if I would write a special march for that occasion, to which I immediately agreed, and the first performance of “The Washington Post March” was at this event at Smithsonian grounds.” [9]

As Sousa said, Wilkins of The Post, introduced the Marine Band’s premiere of “The Washington Post March” at the Smithsonian grounds that day. The performance was met with generous applause.[10] The March, now widely-known, helped thrust a largely unknown Sousa into fame from the day of its premiere. Knowing little about financial matters in his younger years, Sousa sold the piece to his publisher for $35, who submitted the work for copyright in August 1889, and quickly published arrangements for band, piano, and orchestra.[11] Sousa further recounted of the piece:

“A little while after [the March] appeared it was taken up by the dancing masters as the most appropriate music for a two-step, and its popularity increased by bounds until it was strongly identified with the two-step that when I went to Germany touring with my band in 1900 I found that they called the two-step, not a two-step, but 'The Washington Post,' using the name just as they would waltz, polka, &c. Perhaps it is as well known as any piece of music in the world.

A soldier of the late war told me when they were going through a French village they stopped at a little house to get a drink of water and an old peasant came to the door, who invited them in, and when he realized they were American soldiers, he called his little girl of 13 or 14 years and told her to play some American music for the Americans. She sat at her little piano and played 'The Washington Post.' I was told that at the dedication of the monument to Richard Wagner, the German band played as a typical American piece, 'The Washington Post.'” [12]

On that day of the ceremony, eleven student authors took home stunning gold medals for their achievements in writing, and the world gained a lasting, stately March. Reflecting on the piece in 1927, Sousa said: “[The Washington Post March] still retains its popularity and I have every reason to believe it will continue to do so.”[13]

Watch and Listen

Watch the U.S. Marine Band perform The Washington Post March below!

Listen to a 1904 recording of the Sousa Band playing The Washington Post March on the Library of Congress website.

Footnotes

- ^ The Washington Post (1877-1922); Washington, D.C. 1889. “YOUNG AUTHORS: Thousands on the Smithsonian Grounds. MEDALS FOR ESSAYS,” June 16, 1889, sec. General. https://search-proquest-com.library.access.arlingtonva.us/hnpwashington….

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Sousa, John Philip. 2010. Six Marches. Edited by Patrick Warfield. A-R Editions, Inc.

- ^ The Washington Post (1877-1922); Washington, D.C. 1889. “YOUNG AUTHORS: Thousands on the Smithsonian Grounds. MEDALS FOR ESSAYS,” June 16, 1889, sec. General. https://search-proquest-com.library.access.arlingtonva.us/hnpwashington….

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ The Washington Post (1877-1922); Washington, D.C. 1927. “Sousa Tells of March’s World-Wide Popularity,” December 6, 1927, sec. General. https://search-proquest-com.library.access.arlingtonva.us/hnpwashington….

- ^ The Washington Post (1877-1922); Washington, D.C. 1889. “YOUNG AUTHORS: Thousands on the Smithsonian Grounds. MEDALS FOR ESSAYS,” June 16, 1889, sec. General. https://search-proquest-com.library.access.arlingtonva.us/hnpwashington….

- ^ Sousa, John Philip. 2010. Six Marches. Edited by Patrick Warfield. A-R Editions, Inc.

- ^ The Washington Post (1877-1922); Washington, D.C. 1927. “Sousa Tells of March’s World-Wide Popularity,” December 6, 1927, sec. General. https://search-proquest-com.library.access.arlingtonva.us/hnpwashington….

- ^ The Washington Post (1877-1922); Washington, D.C. 1927. “Sousa Tells of March’s World-Wide Popularity,” December 6, 1927, sec. General. https://search-proquest-com.library.access.arlingtonva.us/hnpwashington….

![“Wash., D.C. view of Smithsonian buildings across mass.” (Photo Source: Library of Congress) Wash., D.C. view of Smithsonian buildings across mass. [Ca.188*] Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2016647622/. View of Smithsonian buildings](/sites/default/files/styles/embed/public/3a39396r.jpg?itok=Iz0h3kE1)

![“Wash., D.C. view of Smithsonian buildings across mass.” (Photo Source: Library of Congress) Wash., D.C. view of Smithsonian buildings across mass. [Ca.188*] Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2016647622/. View of Smithsonian buildings](/sites/default/files/3a39396r.jpg)

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)