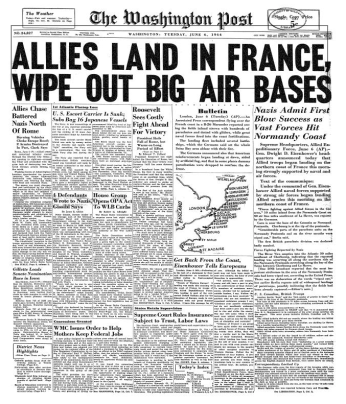

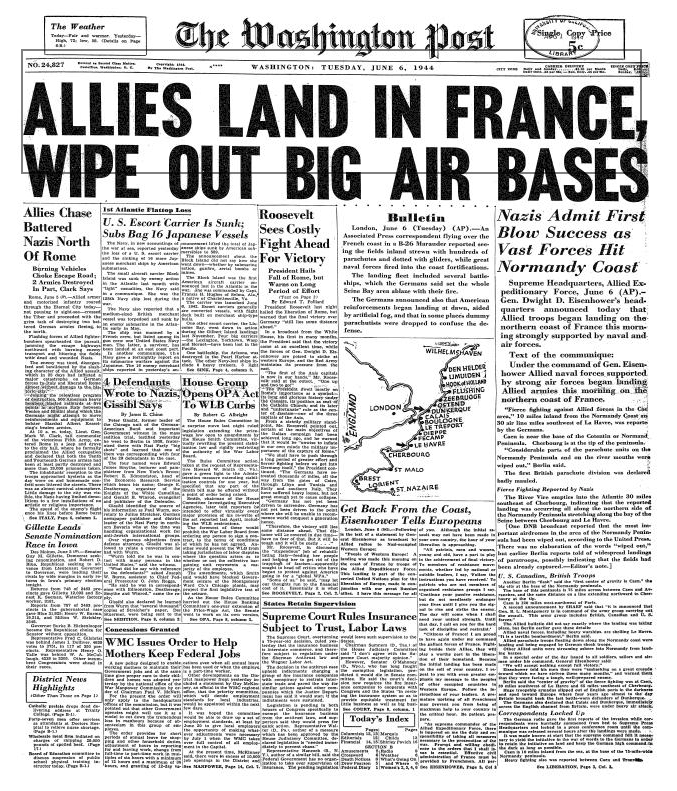

'Simply and literally stunning': Washington Reacts to the D-Day Invasion

The much-anticipated news that Allied forces had invaded France reached Washington in the early hours of June 6, 1944. Word came over a trans-Atlantic radio telephone hookup.[1]

Shortly after 3am, Washington time, officials advised all American news services and broadcasting networks to be prepared for an important announcement in 15 minutes. At 3:32am, Col. R. Ernest Dupuy, General Dwight Eisenhower’s press officer, delivered the news.[2]

Later that day, the Associated Press recounted the highly anticipated announcement in the Washington Evening Star:

A dramatic 10-second interval preceded the official announcement today that the invasion had begun.

[…]

“This is Supreme Headquarters. Allied Expeditionary Force,” Col. Dupuy said. “The text of communique No. l will be released to the press and radio of the United Nations in 10 seconds.

Then the seconds were counted off—one, two three … and finally 10.

“Under the command of Gen. Eisenhower,” slowly read Col. Dupuy, Allied naval forces, supported by strong air forces, began landing Allied armies this morning on the northern coast of France.”

Thus, officially, the world was told the news which it had been awaiting for months.[3]

Americans may have been aware that such an invasion was coming soon, but news that troops had officially stormed the beaches called for block-letter headlines in local papers. It was a major turning point in the war efforts in the European theater, the beginning of the end.

News of D-Day was “simply and literally stunning,” according to Washington Post reporter David Karr. His words captured the city’s emotional reaction:

On the beaches of the Channel coast and on the battlefields behind the lines, our fine, brave lads were dying. More of them will die today, but those who lived and fought must have gained strength and courage from the prayers that were said for them in hundreds of churches and synagogues as people of all walks of life from the President to the lowliest messenger in Government building corridors joined in a plea to the Almighty for speedy victory and a minimum of bloodshed.[4]

From the early morning hours to the late evening, Washingtonians filed into places of worship. A group of Catholic, Protestant and Jewish leaders called Washingtonians to prayer during a Liberation Day program on the radio station WMAL.[5]

“The American and Allied armies return (to the Continent) on this eventful day to liberate the enslaved populations and rescue the soul of humanity,” said one of the faith leaders, the Rev. Edmund A. Walsh, S.J., vice president of Georgetown University.[6]

Washingtonians, alongside Americans around the country, paused to absorb the enormity of what was happening across the Atlantic Ocean. But here in the nation’s capital, they stopped only for a moment to react, before returning to the task of supporting the troops from the Homefront.

D-Day set off a wave of local efforts to support the war. Hundreds of District residents rushed to donate blood at the American Red Cross after hearing about the invasion. The donor center in the Acacia Life Insurance Building quickly reached its daily capacity of 500, according to a report in the Star.[7]

“Mrs. Loretta J. Blackford, director of the center, said that where one telephone had been ringing at intervals yesterday [June 5], volunteer workers were taking calls on four telephones today [June 6] as fast as they could be accepted. Mrs. Blackford counseled citizens to be patient if their appointments had to be scheduled two or three days ahead.”[8]

One group of 40 women employed at a D.C. insurance office made it to a blood bank by 11 a.m. They were able to donate and get back to their desks within the hour.[9]

D-Day’s arrival also sparked a 30 percent jump in the number of Washington residents who inquired about joining the Women’s Army Corps.[10] War bond salesmen used D-Day to ramp up sales of bonds – The invasion closely preceded the launching of the Fifth War Loan Drive, an aggressive campaign to sell bonds which was soon dubbed “Civilian D-Day.”

It Baltimore, too, people experienced the mixed emotions of “jubilance” at the Allies’ advancement and fear for the loved ones fighting abroad.[11] An Assistant State’s Attorney, John C. Weiss, summed up how many felt when he stated in the Baltimore Sun, “I’m tickled to death in one way and scared to death in another.”[12]

Washingtonians could certainly relate. Federal workers reacted to news of the invasion in personal ways. Some stopped by their own churches to pray, others gathered for a brief service in their office buildings.

Staff at the Commerce Department, for instance, bowed their heads for a moment of silence. Workers at the Department of Agriculture gathered for prayer, with Undersecretary Grover Hill presiding. Employees were eager for more news and they wondered about progress of the liberation efforts. But, as the Post reported, they still “put in a full day’s work.”[13]

The employees at Veterans Administration held a quick two-minute prayer service before promising to “redouble their efforts to see that servicemen received their just compensations for the sacrifices they are even now making.”[14] At the Pentagon, D-Day was largely “taken in stride,” as the hundreds of officers who had worked to ensure the troops were fully prepared for H-Hour, “leaned back in their chairs and awaited developments.”[15]

When the initial news reports arrived that June morning, Americans knew the D-Day invasion was a critical achievement for the Allied forces. But for civilians, relying on news bulletins culled from German radio and military communiques, it was hard to know exactly what transpired on the beaches in France, or to know the extent of casualties and injuries.

Harriette Brice, a typist for the Office of the Provost Marshal General, found herself in this position. She was in her office when news of the invasion reached her.

Brice said a prayer for the man who would later become her husband, Frank Leimbach—then a private in the First Infantry Division.[16] Brice, like many, knew her loved one was fighting abroad, but as of June 6, she had no idea whether he was participating in the invasion. It was weeks before Leimbach’s mother, Anna, received a letter from her son.[17]

The 22-year-old from Northeast D.C. was wounded storming Omaha Beach.[18]

“Hello Momer, by the time you receive this you’ll probably know I’m in a hospital somewhere in England due to wounds received on the invasion,” he wrote. As it turns out, Anna Leimbach had not yet heard about her son’s injuries. The letter beat Western Union’s official telegram by at least two weeks.[19]

The Washington Post printed a copy of this letter on the front page of its early edition on June 23, 1944, under the headline, “1st D.C. Boy Wounded on D-Day Writes Home.”[20] It is unclear whether Leimbach’s was truly the first letter received from a local solider, but at the time—when much of Washington was gripped with the same sort of apprehension—it was surely a powerful note to read in the newspaper.

Leimbach would go on to fight in the Battle of the Bulge, come home, marry Brice and have children. That all came later. In the summer of 1944, he was recuperating in the hospital and sending letters home. In one, he reflected on the quiet in the hospital and the terror of war:

Solitude -- quiet, unbroken, sometimes fearful, other times comforting; the kind that only comes from the mixture of the living hell of war and the heavenly, almost forgotten, bliss of peace; the startling comparison of the two, and the sudden realization of how near everything you loved and hated, worshipped and despised, was to vanishing forever. A reverie -- so brutal, yet at times so tender.[21]

Footnotes

- ^ The Associated Press. “’Communique 1’ Gives First News of Invasion: Eisenhower Aide Reads Message to Press and Radio.” The Washington Evening Star, 6 June 1944, p. 3

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Karr, David. “District is Outwardly Calm at Report of Allied Landings.” The Washington Post, 7 June 1944, p. 1

- ^ Allan, Robert Tate. “D.C. Prayers Accompany U.S. Attack.” The Washington Post, 7 June 1944, p. 25

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “Blood Donor Center Flooded With Offers, Red Cross Reports.” The Washington Evening Star, 6 June 1944, p. 4

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Karr, David. “District is Outwardly Calm at Report of Allied Landings.” The Washington Post, 7 June 1944, p. 1

- ^ “Wac Recruit Exhibit Draws Huge Crowd.” The Washington Post, 9 June 1944

- ^ “Invasion News Taken Calmly by Baltimore: People Turn to Prayer, Taverns Close, Amusement Places Empty.” The Baltimore Sun, 7 June 1944, p. 26

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Kluttz, Jerry. “Prayers Mark D-Day in Federal Agencies.” The Washington Post, 7 June 1944, p. 25

- ^ Karr, David. “District is Outwardly Calm at Report of Allied Landings.”

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Brisbane, Arthur S. “Romance, D-Day Agony Recalled: Couple Recall Wartime Washington, Romance, Agony of D-Day.” The Washington Post, 6 June 1984, p. A1

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid. This 1984 Washington Post article references the 1944 printing of Leimbach's letter to his mother.

- ^ Langer, Emily. “War turned solider into a prolific writer; D-Day veteran showered family with letters, which were shared in the hometown paper.” The Washington Post, 1 August 2010, p. C1

- ^ Ibid. This quote comes from Leimbach's obituary in the Washington Post, referencing materials in its archives.

![Small Arms Practice Six OSS recruits watch an instructor shoot a small arm during training at Chopawamsic's Area C. [Source: National Park Service]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2A8CB9F8-1DD8-B71C-070E22100840145DOriginal.jpg?itok=xboGo_08)

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)