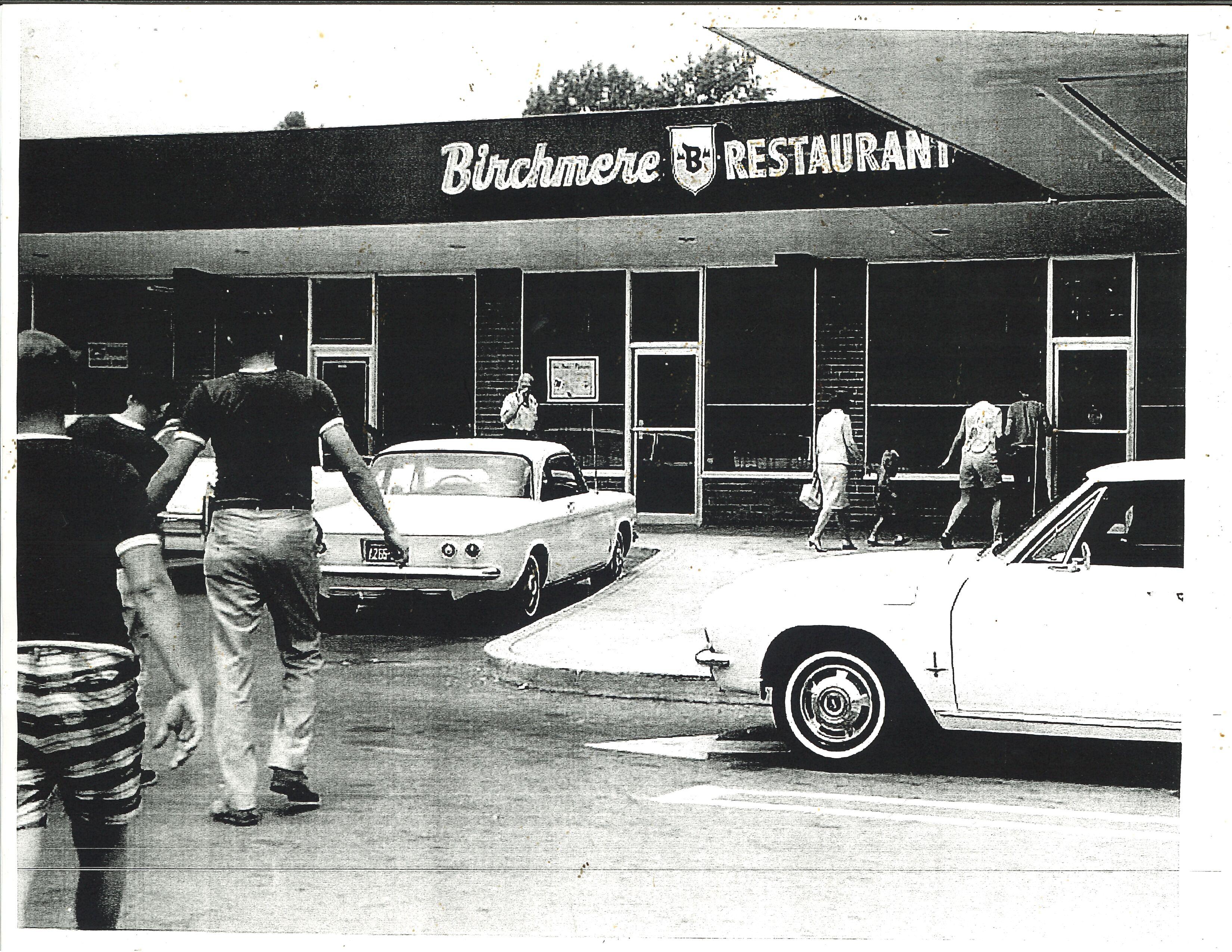

The Birchmere Gets Its Start

In the mid-1960s, when Gary Oelze purchased a restaurant in South Arlington called the Birchmere, he wasn’t thinking about getting into the music business.

“That was the farthest thing from my mind,” he said on a recent afternoon as he sits in the 55,000-square foot venue that now houses the Birchmere, just over the Alexandria line. Today, it’s an internationally renowned music hall that counts among its good friends Linda Ronstadt, Jerry Jeff Walker, Lyle Lovett and Mary Chapin Carpenter.

Oelze first opened the Birchmere, which neighbored the A&P in a Shirlington strip mall, on April 4, 1966. It had a no-frills kind of decor. Oelze, a Kentucky native, would have a piano player or a folk singer a couple nights a week. But at first, the place was a neighborhood bar, not a music hall. In those days, Shirlington didn’t have much going on restaurant-wise, so Oelze did good business around lunchtime off workers at a nearby industrial park. Young government employees who lived in the area would come by for a drink in the evenings.

But the South Arlington neighborhood was changing, as young people were drawn to places like Dale City and Woodbridge and moved further out from the city. “There were all kinds of economics that forced me to try to get people in at night,” Oelze recalled. Around 1974, he started to focus on the music, specifically hiring bluegrass acts.

“I wasn’t what … a champion of the music or anything like that,” Oleze said. But he could count dozens of bluegrass bands in the area and figured they deserved a venue that would take them seriously.

Bluegrass music first gained a following in Washington after World War II, when expats from Appalachia moved to the area for jobs and brought the style of music with them. It didn’t take too long for the Birchmere to cement its reputation as a hub for bluegrass with not only a local following, but a national reputation.

In 1983, the Washington Post wrote that, “Washington is the acknowledged capital of bluegrass, and the Birchmere is the capital’s capitol.”[1]

Oeleze wanted to the Birchmere to be a place that respected bluegrass as a genre. He started putting up little signs that asked the audience to stay quiet during performances, an idea he’ll admit he copied from the old DC club the Cellar Door. And they enforced that rule (Oelze once told the Post about night when he threw out 12 of 24 guests.[2])

“I felt, well why isn’t bluegrass legitimate music. All the other bars had pool tables and juke boxes … or the ball game would be on the TV, and the sound systems were terrible,” Oelze said. The music took a back seat to the other competing sounds and activities.

“I presented [bluegrass] as an honest art form, not just back up music for a hillbilly bar.”

It was this type of environment, one centered on the experience of really listening to music, that distinguished the Birchmere from other bars. Its present location can hold 500 people for a sit-down concert, which is what Oelze really loves. Over the years, as the club has diversified its sound, some acts have even been thrown off by that. As longtime booker Michael Jaworek explained, they were used to having the audience dancing or performing in a space where “the music was part of it but not the focus.”

Vince Gill, a good friend of the Birchmere, said a few years back that it has gotten harder to find a club where you know the audience is really listening.

“I know what it’s like to play a big casino with a crowd that’s fairly indifferent, so it means something to have a place that’s still as reliable as the Birchmere,” he told the Post, “You know the people in the audience are going to be just as passionate about the music as the band on stage.”[3]

In the late 1970s, as the Birchmere found its stride, it also found a partner of sorts in Washington bluegrass band the Seldom Scene. Formed in 1971, the Seldom Scene achieved remarkable acclaim for a band whose every member still had a day job. Their name was, in fact, born from a friend’s quip that the band would be “seldom seen.”

They were a group of people playing music for fun, but as Oelze put it, “they happened … to sound like the best band you’ve ever heard.” Since 1972, the group had been performing at a club in Bethesda called the Red Fox. Oelze would go up there to listen to them play, but soon he tried convincing them to come over to the Birchmere. At first, they agreed to play one Saturday night. That was before presale tickets at the Birchmere, so the line wrapped all the way around the block.

Impressed with the response, Oelze wanted the band at his place on a regular basis, so he offered to double what the group was making at the Red Fox, raising their nightly cut from $400 to $800. Oelze recalls he made the offer to John Duffey, the celebrated mandolin player and founding member of the Seldom Scene who died at 62 in 1996.

“I said to Duffey, ‘You come play for me every Thursday night and I’ll give you $800’ … He said, ‘How are you going to do that?’ And I said, ‘Well, it’s $2 there. It’s going to be $4 here.’” For a little while, the band played the Birchmere every other Thursday while continuing their gig in Bethesda because, according to Oelze, Duffey was “a real loyal kind of guy.” But finally the Seldom Scene became an every-Thursday fixture at the Birchmere and sold out the club for more than 20 years.

“It was a testament to the level of musicianship,” said Jaworek. The Seldom Scene reflected the shifting times—more contemporary and less twangy sound than some of the earlier bluegrass artists.

“The Birchmere and the Seldom Scene both made each other better,” said Tom Gray, a bassist and founding member. As Gray put it, “[Oelze] theorized that if I could get the Seldom Scene here every week, we can build each other’s reputations, and that’s what we did.”

The band’s run at the Red Fox had been successful to a point, but Oelze was more willing to invest in the best sound system. He had a bigger place, and he had a green room for the musicians to use when they weren’t on stage.

“The Birchmere was a serious nightclub, which became our home,” Gray said. As the Seldom Scene gained popularity, all kinds of national acts started coming by the Birchmere to play with them. “You might see Emmylou Harris, Jethroe Burns, Linda Ronstadt, John Prine, Steve Goodman. Everyone wanted to play with them,” according to Oleze.

One of the most famous Birchmere stories, though, is of a performance that wasn’t. Bob Dylan was in the area playing a concert and he called to ask if the Seldom Scene would wait until 10 o’clock to start its last set so he could get over and see it. John Duffey, who is the subject of a new biography, said no, he was going home.

Oelze said that, until he read the Duffey bio, he didn’t realize who answered the phone that night and conveyed the message from Dylan. “It wasn’t me,” he said, “I probably could’ve talked him into staying a little later.”

The Birchmere has moved twice in its history. In 1981, it moved from the original Arlington joint to a site on Mount Vernon Avenue in Alexandria. It has been at the present location, only a few blocks further down Mount Vernon, since 1996. Every space has gotten a little bigger—the first could “legally” hold 200, but they’d stretch that to 250 and only got busted a few times. The second location fit 350.

Today, the Birchmere seats 500 in its main performance space, a listening room that serves sit-down meals. In 2012, the club also introduced a “Flex Space” which allows for a standing crowd of 1,000. Oelze still prefers a sit-down concert, but it’s all part of staying competitive.

Oelze may have gotten its start with bluegrass, but it wasn’t too long before the type of music showcased at the Birchmere evolved to a feature medley of styles including folk, acoustic and singer songwriters.

“This was the capital of bluegrass music. Then of course, that grew into adding folk and acoustic music, and the second generation of bluegrass people came along, like John Prine, Steve Goodman,” Oelze explained, “And then that led to singer songwriters which is my favorite part of the music is the songwriters.”

The club has hosted almost every big name you can think of, Lovett, Rondstadt, Vince Gill, Emmylou Harris and Rosanne Cash to name only a few.

Today, the Birchmere still plays its share of bluegrass. But now it also hosts talented jazz, R&B and pop artists, plus a geographically diverse slate of performers like Latin groups or an Afro-Cuban pop band.

Leading up to the main performance space is a hallway lined with hundreds framed album covers, and Oelze and Jaworek have as many stories about legendary shows and moments from their five decades of history. Ray Charles played one of his last concerts there. There’s the story about how Bill Monroe was playing a bluegrass festival at Wolf Trap and was told he couldn’t play the Birchmere. But, per Oelze, “he wasn’t going to be told what to do.” After the Wolf Trap event wrapped, his bus pulled up to the Birchmere. Monroe and his band got out, walked on stage, played for 40 minutes, walked off and left. “Said nothing to the crowd, to me, nothing!” Oelze laughs.

As Jaworek observed, “A lot of the success that has come later on is because it was a natural growth. It was a natural, organic expansion from the original base without abandoning the base… because we still play folk music, we still play bluegrass as much as we can.”

The growth has brought rewards that go far beyond the bottom line.

“The most rewarding thing is to see how music speaks to, and for, people,” Jaworek reflected, “We have presented music from literally around the world, [and] music is a common … thread wherever you go. The human soul articulates its emotions and its thoughts in music. It always has, and to see that in different music styles and languages is a really … humbling thing.

Footnotes

- ^ Burchard, Hank, “The Birchmere for Bluegrass.” The Washington Post, January 28, 1983: WK14

- ^ Harrington, Richard, “Picking & Choosing: The Birchmere: 20 Years of Bluegrass—& More.” The Washington Post, April 20, 1986: G1

- ^ Ferris, Jedd, “The Birchmere at 50: ‘A Real Deal Music Hall’” The Washington Post, Mach 31, 2016

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)