In Washington, "Taxation Without Representation" is History

It’s been twenty years since Washington’s vehicles underwent a political rebranding.

In May 2000, the D.C. Council announced its plan to change the design of the standard-issue District of Columbia license plates. Some familiar aspects—the lettering, the patriotic color scheme—stayed the same. The big difference was the motto: no longer the neutral and ambiguous “Celebrate and Discover,” but the firm and attention-grabbing “Taxation Without Representation.” It was a stark reference to the District’s lack of representation in Congress and the long struggle for any kind of voting rights at all. Ironically, the Council feared that Congress—which has the power to overturn local legislation in the District—would shut down the proposed redesign. By August, though, an executive order signed by Mayor Anthony A. Williams ensured that residents could obtain their new plates by the end of the year.[1]

The bold change was originally suggested by Sarah Shapiro, a Foggy Bottom resident and local activist, who wanted residents to “confront the rest of the nation with the injustice of our lack of voting rights.”[2] Visitors and tourists, perhaps ignorant of Washington’s unique political circumstance, would be forced to wonder at the motto’s background. “This will make people scratch their heads,” Eleanor Holmes Norton, the District’s non-voting House Representative, told the Washington Post. “They’ll have to ask what it means.”[3]

Most Americans are familiar with the phrase, of course. It brings to mind images of the Revolutionary War—colonists protesting a series of taxes imposed on them by the British Parliament, despite their lack of involvement in its affairs. According to tradition, the battle cry of “taxation without representation is tyranny” originated in Boston, where it featured in such famous displays as the Boston Tea Party. The Declaration of Independence, one of the country’s founding documents, condemns King George III “for imposing Taxes on us without our Consent.”[4] In the popular imagination, the phrase defined the conflict that lead to the creation of our own, more just government.

So how did the phrase come to be associated with Washington, D.C., the center of that government? As it happens, the phrase—and the message it conveys—was part of Washington culture long before it was stamped on our license plates.

Arguments over D.C.’s voting rights are as old as its founding. Facing disagreements over the location of the national capital, the Constitutional Convention of 1787 established a new city which, intentionally, would not be under the jurisdiction of any one state government. James Madison, one of the leading framers, argued that Congress should “exercise exclusive legislation, in all cases whatsoever, over such district,” to avoid any regional disputes amongst the Congressmen.[5] It would have no representatives in Congress, nor any kind of independent local government. The District’s early residents—at least, the white men who actually qualified to vote at the time—would not have the same rights as the residents of states.

The decision was controversial from the very beginning. With the Revolution still fresh in their minds, Washingtonians felt that, once again, they had become subjects of an oppressive government. Their disenfranchisement “does not appear to meet the spirit of the Constitution,” wrote Augustus Woodward, a lawyer practicing in the District. “Nor is it calculated to satisfy…the expectations of those who are locally affected.”[6] Writing in 1801, Woodward was the most outspoken local advocate for the District’s equal representation; his series of newspaper columns called for representatives in both houses of Congress, the right to vote in Presidential elections, and a separate local administration. Some of his efforts paid off: by 1812, Washington had two popularly-elected councils that chose a governing mayor, to conduct local business. But Congress still denied full representation, even while they levied federal taxes.

In 1820, the Supreme Court took up the matter. The decision for Loughborough vs. Blake, written by Chief Justice John Marshall, sought to answer a (supposedly) simple question: “Has Congress a right to impose a direct tax on the District of Columbia?”[7] Washingtonians who believed that “taxation without representation is tyranny” were disappointed. Marshall ruled that it is the duty of all citizens to pay taxes to their government. “Representation is not made the foundation of taxation.”[8]

Though the ruling seemingly settled the question, it didn’t stop residents from campaigning for their voting rights. As the United States expanded and added new territories, the question of D.C. statehood arose again. By the mid nineteenth century, the District was a growing city with a population far greater than many other states—new and old. Washingtonians found an ally in President William Henry Harrison, who supported the creation of a territorial government for the capital. “The people of the District of Columbia are not the subjects of the people of the States, but free American citizens,” he said in his 1841 inaugural address. “If there is anything in the great principle of unalienable rights so emphatically insisted upon in our Declaration of Independence, they could neither make nor the United States accept a surrender of their liberties."[9] Unfortunately, Harrison died of pneumonia shortly after taking office—probably contracted while delivering this lengthy speech in the pouring rain.

The debates continued, but no resolutions seemed solid. Congress implemented various local governments, then revoked or revised them—most famously in 1874, when President Ulysses S. Grant abolished the District’s legislature and territorial governor, replacing them with a three-member commission appointed by the President. Proposals for Congressional representation—and even statehood—appeared every so often. In 1888, New Hampshire’s Senator Henry Blair actually drafted a Constitutional amendment that would give the District full representation without officially becoming a state. It argued that “the people of the District of Columbia are subject to taxation without representation, contrary to fundamental principles of all free government.”[10] Blair believed his proposed amendment would succeed, since “its provisions are based on common fairness and justice,” but it did not pass the Senate.[11] However, it sparked renewed local interest in the cause. When the Evening Star, in an 1895 issue, asked its readers to submit their opinions on District representation, the vast majority were passionately in favor. “Taxation without representation caused the Revolutionary War in 1776,” A.N. Debson wrote them. “What will it cause…in the District of Columbia?”[12]

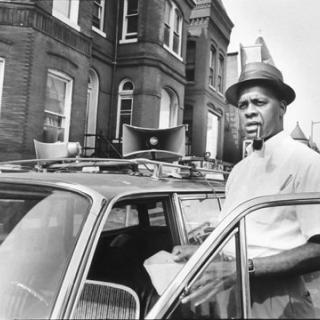

The protests for voting rights certainly became more visible and creative in the twentieth century, with rallying cries still invoking the spirit of 1776. “Taxation without representation is tyranny today as in ’76,” asserted one letter to the Post editor.[13] Clifford Berryman, the political cartoonist whose drawing of Theodore Roosevelt inspired the “teddy bear,” used the slogan in a number of works throughout his sixty-year career in Washington. His recurring character “Mr. D.C.” appeared in Star cartoons from 1907-1949, enduring repeated cases of Congressional abuse and exposing the injustice of Washington’s situation. When Uncle Sam praises freedom and democracy, or reminds citizens of their civic duties, Mr. D.C. watches quietly from the corner of the panel.

Meanwhile, demonstrators took more literal inspiration from the Boston Tea Party. On Tax Day in 1953, some Washingtonians visited Capitol Hill and delivered individual tea bags to Congressional offices. Attached, members of Congress could read a friendly but firm note:

“Dear Congressman: Have a cup of tea with our compliments—and be respectfully reminded that 180 years ago the citizens of Boston rebelled against taxation without representation with their historic ‘Boston Tea Party.’ On March 15, we the voteless Americans of Washington, the capital of world democracy, pay into the U.S. Treasury more Federal income taxes than the people of each of 24 states. In addition, we will this year be taxed 120 million dollars to pay 92 percent of the cost of running the capital city. We believe, like those early Americans of Boston, that ‘taxation without representation is tyranny.’ We earnestly seek your support for home rule. Grant us that right to prove our capacity for local self government, which once was ours (and which was taken from us), as the first step toward representation in the Congress, and full citizenship.”[14]

Twelve years later, the League of Women Voters brought “history up to date” by organizing tea parties all over the city.[15] Attendees, who gathered to discuss local politics, were encouraged to bring an out-of-town guest to raise awareness of the issue. In the 1960s and 1970s, as the prospect of home rule became a reasonable hope, activist groups paraded around the city in old-fashioned buggies, dressed up in colonial costumes. And then, the obvious: in 1973, the two-hundredth anniversary of the Boston Tea Party, members of Self Determination for D.C. threw crates of tea into the Potomac River.

As the protests escalated and residents became more vocal, things did start to change. Campaigns for home rule and Congressional representation received more official support, including from Presidents John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon. In 1964, Washingtonians voted in their first presidential election. In 1970, they elected a non-voting delegate to the House of Representatives. In 1973, the D.C. government as we know it—a locally-elected mayor and council, still subject to Congressional influence—was established. It was progress, but not everything. To many, D.C. was still the “last colony”—represented in Congress, but still without a vote. So the battle cry endured, still invoking the patriotism of the 1770s. “And what was the major complaint of that day? ‘Taxation without representation’ they called it then,” wrote Margaret Aylward in a 1980 letter to the Post editor. Her goal for the future was simple: “Let us complete the revolution.”[16]

When the motto appeared on license plates, it certainly came as a surprise to some people. Some members of Congress thought it a bit harsh and confrontational. Senator Kay Bailey Hutchinson of Texas, the chair of the Senate’s Subcommittee on District of Columbia, thought that Washingtonians “should pride themselves on being the nation’s capital city and have a positive slogan that would be more welcoming."[17] Certain public vehicles drew attention for sporting (or not sporting) the new plates. The Presidential limousine even became a newsmaker when Bill Clinton announced his support for the plates—George W. Bush later removed them, but Barack Obama brought them back. Shapiro, who suggested the new motto, argued that the change is not inherently political, but an important element of D.C.’s identity. For residents, “’Taxation Without Representation’ is not political speech. It’s a fact. People can read it and make up their own minds.”[18]

So, really, it shouldn’t have come as a surprise. Though the phrase came to define revolutionary Boston, “taxation without representation” is just as important to the history and culture of Washington—not as the seat of government, but as a city. Residents and activist groups have been using the phrase since the capital’s founding, supporting a common cause that spans two centuries. They have appropriated it, but made it entirely their own. With the prospect of D.C. statehood back on the table, expect to start seeing it a lot more—maybe we’ll all start drinking more tea, too.

Footnotes

- ^ David Montgomery, “Mayor Signs Order for DC Democracy Plates,” The Washington Post, August 17, 2000

- ^ Mark Fisher, “A Fine Line Makes a Case for District,” The Washington Post, May 16, 2000

- ^ “DC Council Hopes to Use License Plates to Plead for Representation in Congress,” The Washington Post, May 7, 2000

- ^ “The Declaration of Independence,” The National Archives, https://www.archives.gov/founding-docs/declaration-transcript

- ^ James Madison, “The Federalist Papers: No. 43,” The Avalon Project, https://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/fed43.asp

- ^ Augustus B. Woodward, Considerations on the Government of the Territory of Columbia: As They Recently Appeared in the National Intelligencer, under the signature of Epaminondas (Washington: Samuel Harrison, 1801), 3.

- ^ “Loughborough v. Blake, 18 U.S. 317 (1820),” Justia: US Supreme Court, https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/18/317/

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “Inaugural Address of William Henry Harrison,” The Avalon Project, https://avalon.law.yale.edu/19th_century/harrison.asp

- ^ “The District in Congress—Senator Blair’s Plan for Suffrage in the District,” The Washington Post, April 4, 1888.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ The Evening Star, March 16, 1895.

- ^ Mrs. T.B. Young, “Taxation Without Representation” (letter to the editor), The Washington Post, February 4, 1925.

- ^ “Tea Tyranny is Protested by Voteless in Tea Party,” The Washington Post, March 16, 1953.

- ^ “Boston Set the Fashion,” The Washington Post, June 6, 1965.

- ^ “Let Us Complete the Revolution” (letter to the editor), The Washington Post, July 4, 1980.

- ^ Dan Eggen, “States’ Plates Say It: With New Slogan, DC Breaks Mold by Going Negative,” The Washington Post, July 23, 2000.

- ^ Mark Fisher, “A Fine Line Makes a Case for District.”

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)