The History & Survival of Washington D.C.’s Chinatown

When walking the streets of downtown D.C. near Penn Quarter, Washington’s Chinatown is difficult to miss. The vibrant Friendship Archway marks the entrance of the neighborhood, and if you look closely, you’ll even be able to spot markers of the Chinese zodiac on the crosswalks. But despite the area’s seemingly thriving shops and restaurants, Chinatown’s Chinese population today is estimated to be as low as 300.[1] Things weren’t always this way, though. In fact, Chinatown was first located in a different D.C. neighborhood altogether. So how did Washington’s Chinese community first develop? What was Chinatown like before, and how and why did that change?

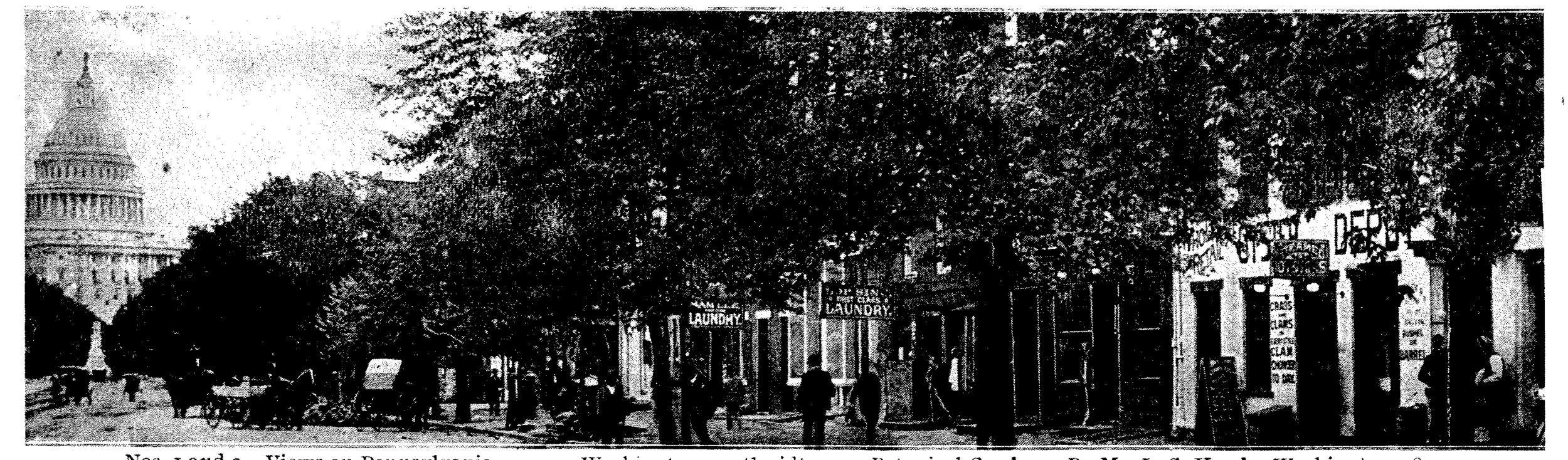

In 1851, the first documented Chinese person registered an address on Pennsylvania avenue, the street that would grow to become D.C.’s first Chinatown.[2] Although the 1890 U.S. Census recorded D.C.’s general Asian population to be just 100 people,[3] the Chinese population was large enough for The Washington Post to observe the “residents of a local Chinatown” in 1893.[4]

By 1898, Washington’s Chinatown warranted a feature in The Evening Star. Although the article, entitled “A Trip to Chinatown,” exoticized Chinese people and described them as “moon-eyed Mongolians,” “orientals,” and “celestials,” it also noted that “not all” of those in Chinatown were merely “Laundrymen,” describing most Chinese people as “successful merchants.”[5]

According to the article, the original Chinatown included “some half dozen buildings on the south side of Pennsylvania avenue between 3rd and 4 ½ streets, together with a row of old brick houses on the west side of 4 ½ street just below the avenue.”[5] This location was closer to Capitol Hill, and today, the East Wing of the National Gallery of Art stands in its place.[6] Though in “limited quarters,” “scores of Chinese” people inhabited this area and could be seen daily sitting and “smok[ing] a pipe with their countrymen.”[5] Most D.C. Chinese maintained stores on the ground level of these buildings and used the upper spaces to live, and many people lived “within a very small compass.”[5]

Laundromats were by far the most widespread and popular businesses, but there were also a few Chinese restaurants, as well as general stores that sold Chinese cups, pots, tea, candy, and produce like lychee and bamboo.[5] Although Chinatown’s businesses were open to all, Chinese immigrants were wary of outsiders. The Evening Star commented that though Chinese immigrants “chat like magpies,” “the moment you step in the company which has just been talking to a beat a women’s sewing circle, [they] will drop into a sphinx-like silence, from which your utmost persuasiveness and amiability will scarcely coax it.”[5] By the 1920s, the census recorded this tight-knit community to be 369 people,[7] though it’s reported that Chinatown in fact housed as many as 700 people.[6]

But just when Washington’s Chinese managed to build a home, construction of the Federal Triangle threatened their community. The Evening Star covered Chinatown’s annual Lunar New Year celebration on Pennsylvania ave. in 1928; but by 1932, the newspaper observed that “much of the former Chinatown environment…disappeared in the destruction of old buildings for the Municipal Center and the Federal Triangle and Mall development.”[8] Although it’s difficult to find first hand perspectives of the displacement from Chinatown residents, the construction projects definitely sparked some controversy. An Evening Star piece from 1935 implored people to “look at old Pennsylvania avenue.”[9] “Remember…Chinatown?” read the article. “Nothing of that is left. What happened to it? The Government almost made a south side clean sweep.”[9]

The Chinese community wasn’t one to give up, though. Led by the On Leong Chinese Merchants’ Association, they regrouped and decided to remake Chinatown on H St. NW between Sixth and Seventh St., where it still stands today.[10] According to the papers, this “new Chinatown…straggl[ed]” initially, since “Government projects forced most of the Chinese merchants off of Pennsylvania avenue” rather quickly; but it was still developed enough to host a Lunar New Year celebration in February of 1934.[10]

Washington’s Chinese demonstrated profound resilience in the face of the city’s rapid changes, and after the repeal of the Chinese Exclusion Act and the Geary Act, their population only grew. According to the census, the population of D.C.’s Chinese rose from 398 to 1,825 between 1930 and 1950.[7] During these years, Chinatown thrived and maintained its place as the center for Chinese community service, cultural celebration, and political organizing.

But in the years leading up to 1970, more and more Chinese immigrants settled outside of the city, and Chinatown’s population started to wane. Where in 1950 a majority of Chinese lived in D.C. compared to Maryland and Virginia, by the 1970s, an overwhelming majority lived in the suburbs rather than in the city.[11] It’s difficult to pinpoint a direct cause of this shift, but there were some notable contributing events.

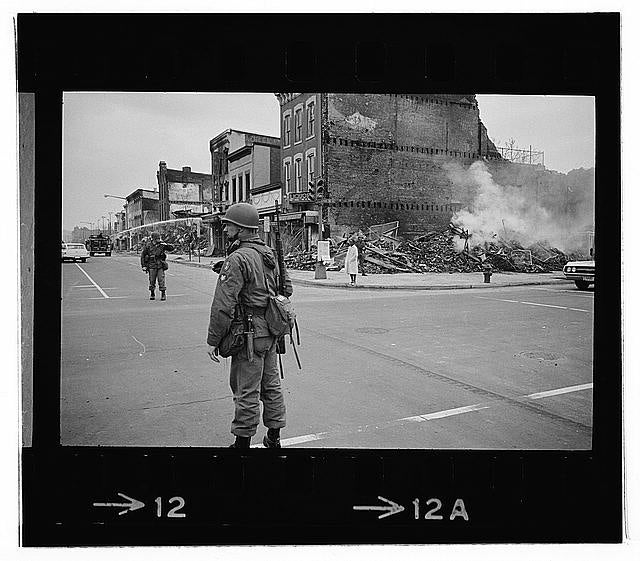

One possible factor was the violence that followed the 1968 assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King. While the unrest primarily involved African-American communities; Chinatown was also impacted, as various long time residents recalled in Through Chinatown’s Eyes, a documentary by Penny Lee, Lisa Mao, and the 1882 Foundation. In the film, Ton Chin, former Chinatown resident, remembers that “There was always tension between blacks and whites.”[2] “I always felt like [Chinese-Americans] were in the middle,” says Chin.[2]

Chin recalls the day of the riot: "My dad had a laundry and so we had a big glass window. And I remember just hearing a crash at night, somebody had thrown a brick through my dad’s window. We were just kids, I was just eighteen... It was frightening. We could look out the window and see fires up and down seventh street, it was terrifying."[2]

Chin’s family’s experience was not the norm -- most Chinese-American businesses and families weren’t directly targeted, and some remember African American neighbors helping prevent looters from ransacking Chinese-owned businesses. Still, Harry Chow explains, “My father was uncomfortable [after the riots]…We didn’t know how to fit in. He didn’t feel safe anymore, so he thought about moving to Maryland.”[2]

He wasn’t the only one, as Meta Yee remembers: “People started moving out to the suburbs. We lost a lot of businesses, we lost a lot of neighbors. And Chinatown throughout the years has gotten smaller and smaller and smaller because we didn’t have the business to sustain it once everyone started moving out to the suburbs.”[2]

After the fires from 1968 were extinguished, development presented the next big challenge. Various building projects soon began to encroach upon Chinatown. In the late 1970s, the city announced plans for a new Convention Center, which would have displaced thirty-eight Chinese-American households and cost hundreds of jobs.[12] In the face of the threat, the Chinese community mobilized and successfully fought to move the center two blocks to the west.[13]

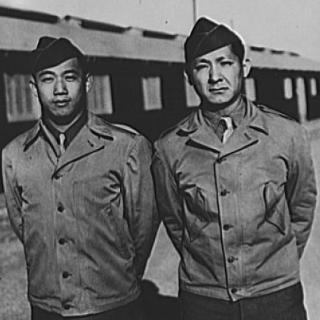

As the area continued to develop, though, it became more difficult for Chinatown residents to fend off construction in their neighborhood. In 1980, Fung Dak Lee lost his laundry business due to the expansion of George Washington University, despite G.W. students lobbying behind him.[14] “I’ve been in this business all my life,” Lee protested in a Washington Post article.[14] “I’m mad and I feel shorted.” Lee’s father had started the business in 1920, and Lee worked at the business from the age of 10 years old. Even after fighting in World War II and gaining citizenship, Lee returned to the laundry business. “I’m an old man,” lamented Lee.[14] “I say to the people at G.W., why not let me stay just a few years, and then you can have the store?”[14]

For many, the opening of MCI Center – now Capital One arena – in 1996 was the final blow. Shirley Woo, now 71, remembers a Chinatown that was more residential. Harry Chow observed, “it became so expensive to live and run shops that the mom-and-pop Chinese grocery stores that used to cater to the Chinese community could no longer afford it. They're gone, and people have moved to the suburbs.”[15]

Though the community is smaller than it used to be, there are still those in Chinatown who are fighting to stay in the city.[15] Several years ago, tenants of the Museum Square apartment building, which houses half of Chinatown’s Chinese residents, were almost evicted.[16] The building’s owner wanted to tear the building down and rebuild to match gentrified buildings in the area. After the Chinese community organized and protested, the D.C. Court of Appeals upheld a ruling in their favor in September of 2016.[16]

As the tenants of Museum Square remind us, Chinatown is far more than just a great photo-op or tourist destination; it’s a historic home. Washington’s Chinese community has a rich and longstanding past, and we shouldn’t forget how hard they’ve fought to maintain their place in the city.

Footnotes

- ^ Yanan Wang. “D.C.’s Chinatown has only 300 Chinese Americans left, and they’re fighting to stay.” The Washington Post, 18 July 2015.

- a, b, c, d, e, f Through Chinatown’s Eyes: 1968. Directed by Penny Lee and Lisa Mao, Tiger Sisters Productions, 2016.

- ^ 196 in Maryland, 100 in D.C., and 71 in Virginia. Campbell Gibson and Kay Jung. “Population Division: HISTORICAL CENSUS STATISTICS ON POPULATION TOTALS BY RACE, 1790 TO 1990, AND BY HISPANIC ORIGIN, 1970 TO 1990, FOR THE UNITED STATES, REGIONS, DIVISIONS, AND STATES.” United States Census Bureau. Working paper series (United States. Bureau of the Census. Population Division), no. 56. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Census Bureau, 2002.

- ^ "HERE AND THERE." The Washington Post (1877-1922), Oct 29 1893, p. 16.

- a, b, c, d, e, f The Evening Star, January 8, 1898 , Washington (DC), District of Columbia, p. 19

- a, b Marc Fisher. "We Sell'." The Washington Post (1974-Current file), Jan 29 1995, p. 11.

- a, b Campbell Gibson and Kay Jung. “Population Division: HISTORICAL CENSUS STATISTICS ON POPULATION TOTALS BY RACE, 1790 TO 1990, AND BY HISPANIC ORIGIN, 1970 TO 1990, FOR THE UNITED STATES, REGIONS, DIVISIONS, AND STATES.” United States Census Bureau. Working paper series (United States. Bureau of the Census. Population Division), no. 56. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Census Bureau, 2002.

- ^ The Evening Star, November 21, 1932 (DC), District of Columbia, Page 17

- a, b The Evening Star, June 10, 1935 (DC), District of Columbia, Page 41

- a, b The Evening Star, February 13, 1934 (DC), District of Columbia, Page 17

- ^ 1950 Census recorded 1,825 in D.C., 795 in MD, and 565 in VA. 1970 Census recorded 2,582 in D.C., 6,520 in MD, and 2,805 in VA. Campbell Gibson and Kay Jung. “Population Division: HISTORICAL CENSUS STATISTICS ON POPULATION TOTALS BY RACE, 1790 TO 1990, AND BY HISPANIC ORIGIN, 1970 TO 1990, FOR THE UNITED STATES, REGIONS, DIVISIONS, AND STATES.” United States Census Bureau. Working paper series (United States. Bureau of the Census. Population Division), no. 56. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Census Bureau, 2002.

- ^ William H. Jones "Chinatown Rejuvenation Urged: Many Favor Trade and Community Center." The Washington Post, Times Herald (1959-1973), Feb 25 1973, p. 2.

- ^ Marc Fisher. "We Sell'." The Washington Post (1974-Current file), Jan 29 1995

- a, b, c, d Jeffrey Adam Baxt. "Chinese Laundry Vanishes After 23 Years as University Expands Medical Center." The Washington Post (1974-Current file), Feb 28 1980, p. 1.

- a, b Yanan Wang. “D.C.’s Chinatown has only 300 Chinese Americans left, and they’re fighting to stay.” The Washington Post, 18 July 2015.

- a, b Perry Stein. “Last remaining Chinese residents in Chinatown score a victory in court.” The Washington Post, Sept 27 2016.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)