The District's Own Asian Gatsby: Koreagate & the "Tongsun Park Problem"

Depending on how you look at it, the 1976 Koreagate scandal didn’t really start with Tongsun Park. But when the media caught wind of “the most sweeping allegations of congressional corruption ever investigated by the foreign government,”[1] Tongsun Park’s charm and personality made him an entertaining antagonist.

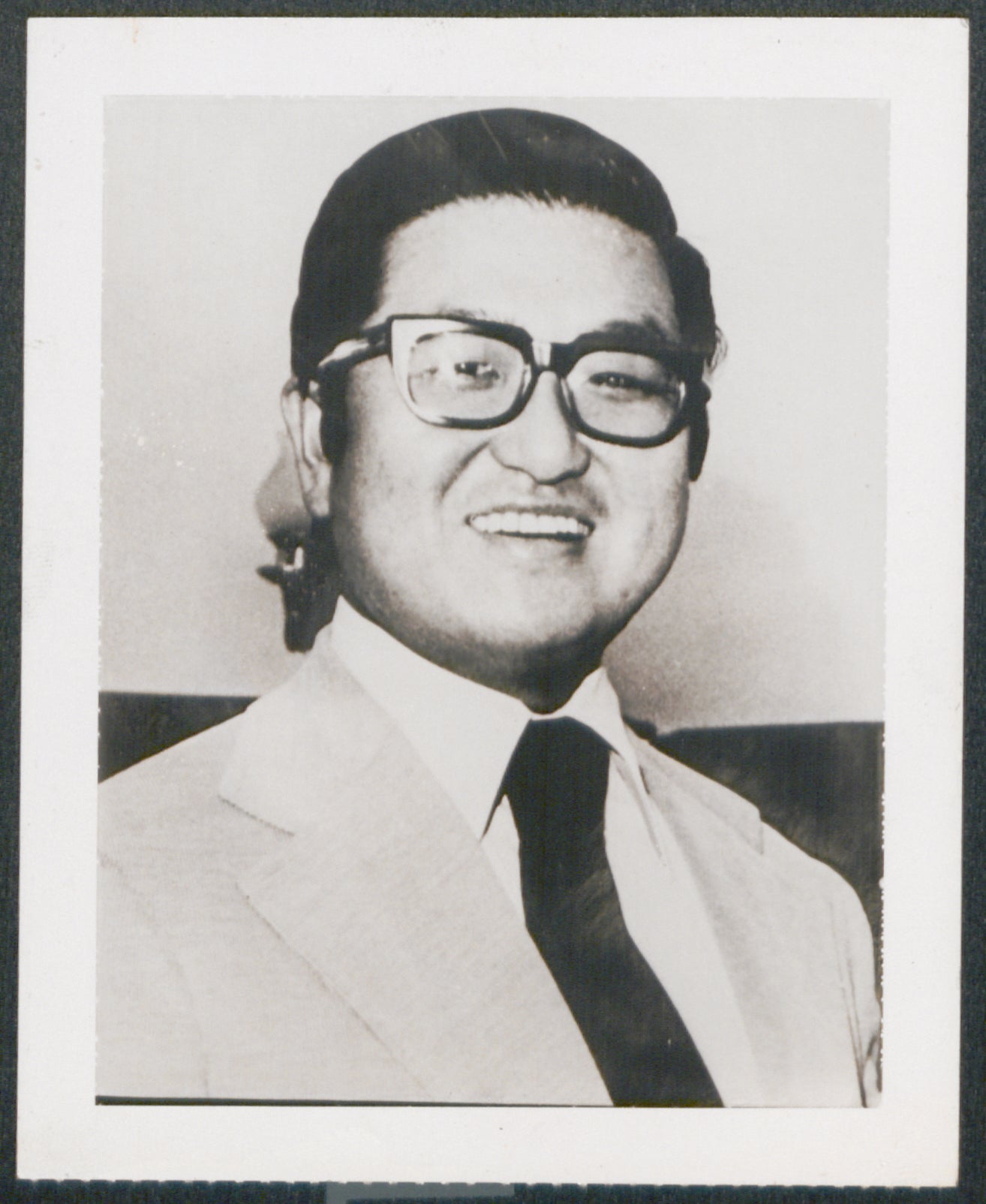

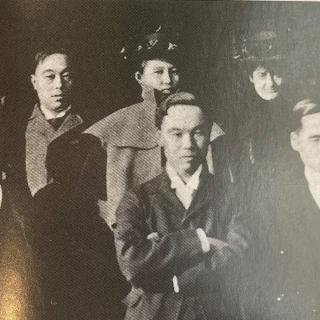

Part of the intrigue was that Park’s story didn’t conform to the stereotypical immigrant narrative. Park, born in 1935, grew up with wealth; his family was in oil, and some even referred to him as ‘the Onassis of the Far East.’[2] When he left Korea for the U.S. in the late 1950s to attend Georgetown University, he leveraged that privilege to his gain. He threw elaborate parties,[3] and soon, he was president of his freshman class. Parties led to popularity; popularity led to influence. It was hardly a revolutionary technique, but it was successful - so much so that Park founded the ‘Georgetown Club’ in 1966 to continue the festivities.[4]

Park purchased 1530 Wisconsin Ave. NW to serve as club premises, and it didn’t take long before the Georgetown Club became a regular gathering spot for D.C.’s most influential.[5] Club goers included Gerald Ford, then House Speaker Carl Albert, then Democratic Majority Leader Thomas P. O’Neill, and “scores of other representatives, senators, and administrators.”[5] The club even hosted Luci Johnson’s (daughter of then President Lyndon B. Johnson) wedding rehearsal dinner.[5]

Nearly everyone who encountered Tongsun Park got along with him. He was charming, amiable, and generous. “Lots of people in this city liked him a great deal. You would see Jerry Ford or former Attorney General William Saxbe at his house, and I wasn’t surprised. He could make friends in a very wide circle,” remembered Representative John Brademas.[6] By the 1970s, Park’s opulence – “expensive homes, lavish Embassy Row parties, worldwide jet travel and purchase of his own downtown office building”[7] – made him a Washington celebrity.

But while Park was assimilated enough to effortlessly navigate Washington’s most elite circles, his perceived ‘foreignness’ allowed him to retain a necessary level of mystery. As a former guest of the Georgetown Club recalled, “Whenever I asked what he did for a living, he would mumble that he was some kind of businessman, had something to do with rice, mumble, mumble.”[8] “Many who came [to Park’s club] will admit they found Tongsun different, exotic, perhaps enigmatic. Americans have always found the oriental different. Remember the immigration laws, the Japanese camps,” commented The Washington Dossier.[9] With both money and mystery, Park became known as the District’s “Asian Gatsby.”[1]

What club-goers didn’t know was that before Tongsun Park founded The Georgetown Club, he returned to South Korea. As in D.C., Park made friends with the nation’s most powerful, including those in President Park Chung Hee’s administration and those involved with the Korean Central Intelligence Agency (KCIA).[1] In 1965, a year before he founded his club, Park offered to work with the KCIA, saying he’d use his congressional connections to help South Korean interests provided they’d help him become “the sole agent” for South Korean rice purchases from the U.S.[3] Not long after this, President Park named Tongsun Park the chief intermediary between Korean rice-buyers and U.S. suppliers.[3] As was later revealed in the Department of Justice’s 1976 investigation, Park primarily worked with congressman Richard T. Hanna (D-CA), using rice sale commissions to provide financial “gifts” and campaign contributions to members of Congress.[3]

When the news of Tongsun Park’s involvement with the KCIA first broke, the District found itself in a frenzy. Corruption on Capitol Hill, the KCIA, and a Korean “Gatsby?” The articles seemed to write themselves. Journalists named the scandal “Koreagate” and promised the juiciest story of congressional corruption yet. But despite all the build-up, it didn’t take much for the case to fizzle out. The Washington Post reported early on that at least 100 members of Congress had “come into contact with the Koreans and their sometimes smothering intentions.”[10] As it turned out, though, many who received contributions from Park protested that they hardly knew him, let alone his ulterior motives.[11]

When the Department of Justice indicted Park with thirty-six felony accounts, he had already left for South Korea, and there was no extradition treaty that could secure Park’s return.[12] Park finally testified in exchange for his immunity in spring 1978. In a disappointing conclusion, fewer than 10 members of Congress were implicated by his testimony, and most of them had already left Congress.[13] As The Post admitted, the press had blown the story “way out of proportion, in a post-Watergate race to be the first with gory details.”[13] “Nothing we could have done would have met the expectations raised by the press,” remarked a House investigator.[13]

One of the problems investigators and prosecutors identified in retrospect was an over-focus on Tongsun Park.[13] Though Park was a key player and may even seem to be the instigator, the story really begins with the South Korean government and the KCIA. South Korea was worried about its dependence on American aid, American disapproval of President Park Chung Hee’s rule, and Nixon’s withdrawal of American troops in South Korea; Tongsun Park provided an opportunity they were likely already searching for.[3] Nevertheless, he was an easy character to build a scandal around, and it was Park’s name that resonated in the minds of Americans, especially those in the D.C. metropolitan area.

By the 1970s, the Korean-American population numbered 35,000, making them one of the largest ethnic groups in the DMV. They worked hard to adjust to American life, often “holding two jobs, working long hours, and living frugally.”[14] The Koreagate scandal threatened their stability and produced what they called “the Tongsun Problem.”[14] As Doyung Lee, president of the Korean Association of Greater Washington, explained, “Koreans try to be good citizens, but when Tongsun Park was in the news it hurt all of us.” Lee was quick to differentiate Park from most Korean-Americans, stating that “[Park] spent a lot of money, but he never did anything for us. We had trouble getting jobs after that, our children were teased at school. It was all very upsetting.”[14]

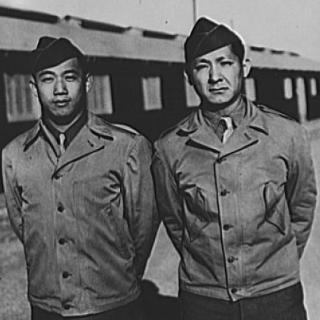

Karate studio owner Jhoon Rhee also fell victim to ‘the Tongsun Problem.’ Rhee had worked tirelessly to establish his studio on Capitol Hill, and his school boasted Redskins’ football coach George Allen, Muhammad Ali, Bruce Lee, then House Speaker Carl Albert, and other congressmen as patrons; but his business “dried up” after Koreagate publicity.[15] To make matters worse, Rhee was subpoenaed by the Justice Department on the mere grounds that congressmen frequented his studio.[15]

Even those with zero connections to Congress were hurt by the scandal. “When people go look for a job, they have been told ‘Oh, you need money too? Why don’t you ask Tongsun Park?’”[16] recounted Reverend Sun, pastor of the Korean United Methodist Church. Sun explained that Tongsun Park was the exception rather than the rule; most Korean immigrants weren’t wealthy, and they were more concerned with building a new life than they were government. As Sun remarked, “Many Korean-Americans are Americans first."[16]

Diplomatically, Koreagate didn’t result in any lasting damage to U.S. and South Korean relations, so it seems ironic that Korean-Americans were the ones who suffered most from the effects of Park’s legacy. But perhaps it’s also not too surprising. As even this article testifies, it’s easier to tell the story of a villain than it is to explain a geopolitical relationship. Most Americans today have long forgotten about Koreagate. As we remember the story, though, the words of one Washington Post journalist still resonate: despite the “dishonest actions” of people in power, “may we see Koreans as they are – friends and allies.”[17]

Footnotes

- a, b, c “Korean Ties to Congress are Probed,” Scott Armstrong and Maxine Cheshire, The Washington Post (1974-Current file); Oct 15, 1976.

- ^ “Tongsun Park's Club How the Korean Built His Georgetown Base,” Phil McCombs The Washington Post (1974-Current file); Oct 16, 1977

- a, b, c, d, e The Party’s Over: Sex, Gender, and Orientalism in the Koreagate Scandal of the 1970sShelley Sang-Hee Leehttps://muse.jhu.edu/article/706772/pdf

- ^ “Tongsun Park's Club How the Korean Built His Georgetown Base,” Phil McCombs The Washington Post (1974-Current file); Oct 16, 1977

- a, b, c “Knauer Feted,” June 24, 1971, Evening Star, Washington (DC), District of Columbia, p. 41

- ^ “Tongsun Park's Touch: Brademas Couldn't Say No to Korean The 'Charming' Touch of Tongsun Park,” T. R. Reid, The Washington Post (1974-Current file); Aug 10, 1977.

- ^ Tongsun Park's Club How the Korean Built His Georgetown Base,” Phil McCombs The Washington Post (1974-Current file); Oct 16, 1977

- ^ Shaw, “Stakes Are Global in Korea Lobby Probe,” 28.

- ^ Warren Adler, “Tandy Meem Dickenson: A Washington Story,” Washington Dossier, September 1977, 58

- ^ “Koreans Lavished Largess On an Incurious Congress: Heavy-Handed,” Charles R. Babcock and T. R. Reid The Washington Post (1974-Current file); Jul 31, 1977.

- ^ “Many Deny Knowing Tongsun Park,” Warren Brown,The Washington Post (1974-Current file); Sep 7, 1977;

- ^ “Tongsun Park Indicted by U.S. Jury,” Charles R. Babcock, The Washington Post (1974-Current file); Sep 1, 1977.

- a, b, c, d Koreagate: Bringing Forth a Mouse, But an Honest One,” Charles R. Babcock, The Washington Post (1974-Current file); Oct 9, 1978.

- a, b, c “Korean-Americans: Pursuing Economic Success,” Sandra G. Boodman, The Washington Post (1974-Current file); Jul 13, 1978.

- a, b “Koreans in DC Affected by Bribery Scandal,” Pacific Citizen, February 4, 1977, 2.

- a, b 6. “Koreagate Spurs Anti- Korean Bias, Says Cleric,” Pacific Citizen, October 27, 1978, 1

- ^ “Tarnishing the Image of an Entire Nation,” Raymond F. Howard, The Washington Post (1984-Current file); Oct 27, 1978

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)