Anne Royall and the President's Clothes

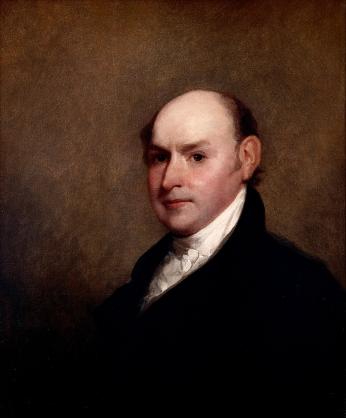

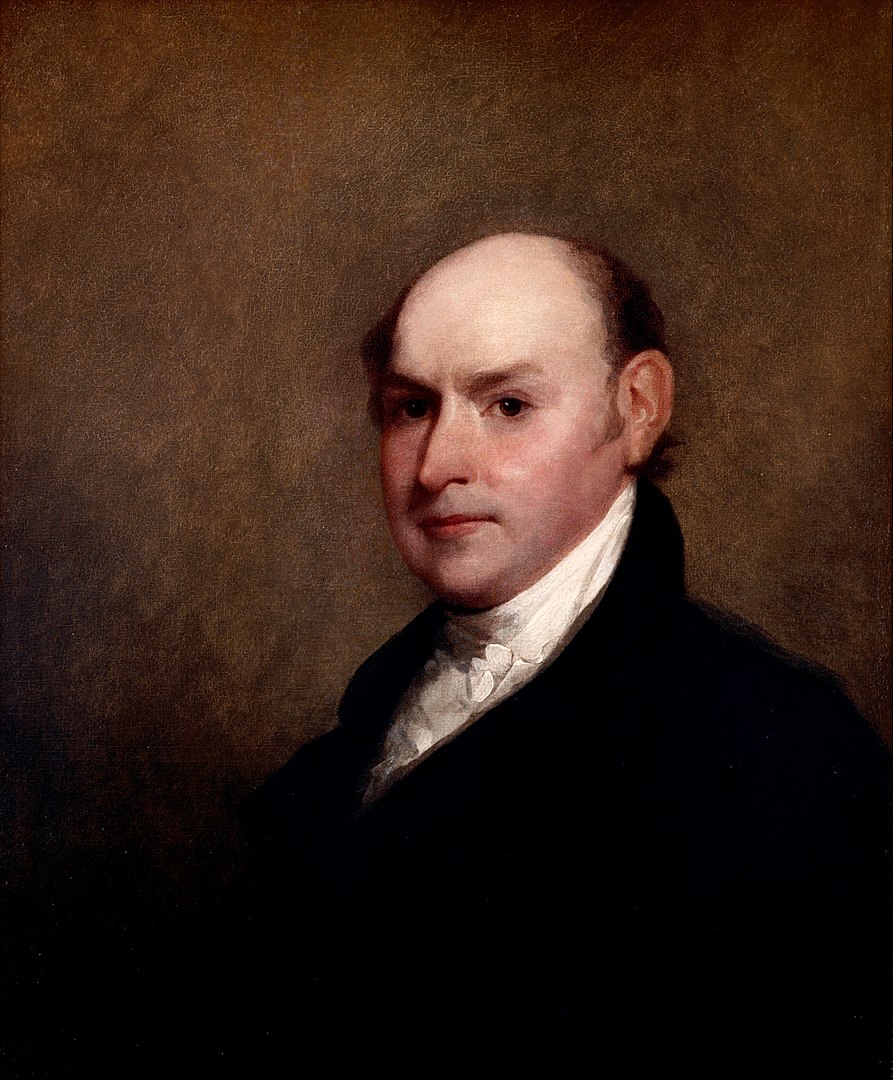

When the stresses of life in Washington became too much, John Quincy Adams—the President, Secretary of State, Congressman, ambassador, and President’s son—calmed his nerves by taking early-morning swims in the Potomac River. In a move that might be considered questionable by today’s standards, he especially liked to soak in the brisk, cold water wearing nothing but his own skin. According to local lore, it once got him into a bit of trouble.

Anne Royall, a travel writer and investigative journalist based in the District, wanted to score an interview with Adams. Though she had interviewed several other politicians for her weekly newspaper, The Huntress, he proved elusive. When she found out that the President usually spent his mornings swimming in the Potomac River, she saw her chance. One morning, Royall went down to the Tiber Creek—a tributary of the Potomac now hidden underneath Constitution Avenue NW—and spotted a little pile of clothes on the shore. Sure enough, they belonged to the President. She sat on them and refused to give them back until Adams, now trapped in the river, agreed to answer her questions.[1]

It’s a funny story and an amazing insight into the early days of Washington, when you might casually stumble upon your country’s leader skinny dipping in the river. But how true is it? Did Anne Royall steal the President’s clothes? As ever, the truth is slightly more complicated.

John Quincy Adams really did love to swim in the Potomac River. When he moved to Washington in 1817, taking up the position of Secretary of State under President James Monroe, he began the routine of rising early and taking some kind of exercise. As the summers grew unbearably hot, he found relief in the river’s cold water. A diary entry from 1819 describes his daily swims:

“The range of my rising hour is from four to six. The average is five, which if I could observe it the year round, would be approaching as near to regularity as the imperfection of my nature will admit. At the times when the tides in the river serve, I bathe in the Potowmac near the Bridge. The walk to the spot is a mile and a half, and with half an hour in bathing, it takes from an hour and a half to two hours…I find it, as always, conducive to health, cleanliness, and comfort.”[2]

Clearly Adams loved routine and regularity, so the swims continued even after he was elected President. Sometimes he brought his manservant, Antoine, with him—most times, he seems to have preferred the quiet solitude. As he became more confident in the water, he even challenged himself to swim longer distances, sometimes staying in the water for three hours. On August 25, 1824, he decided to swim across the river, accompanied by his son, John:

“Swam across the Potowmack with John—Antoine crossing at the same time in a boat, close at hand to take us in, had we met any insuperable difficulty. I was exactly an hour and a half from shore to shore. John was ten minutes less.”[3]

Though his doctors and wife warned Adams that this level of physical exertion was dangerous for a man approaching sixty, colleagues praised the President’s dedication and trim figure. “Mr. Adams ascribes his uninterrupted health during the several sickly seasons he has lived in Washington to swimming,” reported the Congressman Charles Jared Ingersoll. “I have no doubt that it is an excellent system—he is extremely thin.”[4] Adams seems to have ignored all the warnings, because he was still taking occasional swims in 1846, after his seventy-ninth birthday.

But were President Adams’s swims…clothed? Probably not. As it turns out, bathing suits—especially for men—weren’t really a thing in the early nineteenth century. Men could swim in their underwear or breeches, but it was more common for them to just ditch the clothes altogether. However awkward it must have been to stumble across the President on one his morning swims, it wasn’t as if Adams was a complete social deviant. In fact, he did accessorize a bit: Stratford Canning, the British Ambassador, saw Adams “one morning, at an early hour, floating down the Potomac, with a black cap on his head and a pair of green goggles on his eyes.”[5]

Given the regularity of the swims, it makes sense that, in 1829, a local newspaper reported an amusing story about President Adams’s morning exercise. The source was Edward Everett, a Congressman from Massachusetts, who described a strange encounter with Washington’s most notorious journalist, Anne Royall:

“Mr. Everett was standing alone one morning on the Washington side of the bridge built across the Potomac, as early as four o’clock, when he was suddenly accosted by Anne Royal, with a request that he would favor her with an introduction to the President, the executive chair being at that time filled by his friend John Quincy Adams. ‘Would you wish to see him now ma’am,’ replied Everett…As was perhaps expected, the lady at once replied in the affirmative, when Everett immediately took her towards the railing of the bridge and told her to look over. She did so, and in a few moments the chief of the Republic appeared in the waters of the Potomac, kicking and plunging from under the arch, where he was quietly enjoying the comforts of a cold bath, a refreshment of which he is said to be very fond. This was Mrs. Royal’s first formal introduction to President Adams.”[6]

This little blurb is probably the origin of our local legend. The later version of the story, which sees the gutsy Royall take more control over the situation, didn’t appear in print until 1886. The writer Seaton Donoho, reminiscing on his childhood for an edition of The Brooklyn Magazine, described the incident and almost painted himself as a witness. And his goal wasn't to relate a fun, amusing local story, either—to Donoho, this was a mortifying moment for the President. Royall, the “vengeful madam,” is the clear villain of the story.[7] He perpetuated the stereotype that, in early Washington, Royall was trouble.

Just as the story suggests, Royall was a journalist with a reputation...both good and bad. At fifty-seven, she decided to support herself by embarking on a career in writing, traveling all over the country and publishing accounts of her adventures. But these weren’t simple travel books—Royall’s accounts of the people, places, and ideas she encountered were often scathingly honest and critical. By the time she moved to Washington, in 1829, she was already well-known as a woman who voiced her opinions, no matter how offensive. Her weekly newspapers—which she wrote, edited, and distributed independently—unapologetically criticized corrupt, hypocritical politicians. A lot of people in the District didn’t take kindly to her, especially after she instigated some drama in her Capitol Hill neighborhood. In a now-notorious and very public trial, she was accused of being a "common scold."

But trouble with the law aside, Royall seemed to revel in her notoriety. Even after she gained a bad reputation amongst Washington journalists, she continued to publish her newspapers and expose alleged corruption in the government. This attracted the scorn of many of her contemporaries—not only was she performing a typically masculine profession, it was considered unladylike to be bold, aggressive, and critical. So, when the story of her encounter with President Adams began to circulate in Washington, most people readily believed it.

However, Royall’s biographer Elizabeth J. Clapp doubts the story’s authenticity—even the earlier 1829 version.[8] For one thing, the dates don’t match up—Adams’s presidency ended in March 1829, so he probably wasn’t swimming in the river that summer. Royall didn’t even move to Washington until later that same year—she didn’t establish her newspapers until 1831. What’s more, Adams and Royall were actually friends. They first met in 1824, when Royall (a Revolutionary War widow) travelled to Washington to claim her late husband’s pension. Not only did Adams support her appeal to Congress, she visited his home and took tea with his wife. Later that year, after she left Washington, she visited the elderly ex-President John Adams in Massachusetts and assured him that his son and daughter-in-law were in excellent health.[9] It seems unlikely that Royall would need to corner Adams so dramatically just to get an interview.

It’s hard to put all the pieces of this puzzle together, but the evidence does suggest that, contrary to the popular story, Royall didn’t actually confront the President during his morning swim. Some things are certain, at least: Adams did love to swim in the Potomac, while Royall was a fearless journalist who defied society’s boundaries for women. In fact, some sources still claim that she was the first journalist granted an interview with an American President—even if circumstances were less exciting.[10]

And, in all fairness, it’s easy to see how such a funny, strange story took on a life of its own. It’s been a staple of Washington lore since the nineteenth century! Until 1915, there was even a rock—known as “Anne Royall’s Rock”—that marked the supposed spot of the encounter on the banks of the Potomac.[11] But now we know the simpler truth: Adams skinny dipped in the Potomac River every morning, but his clothes were never held hostage.

Footnotes

- ^ Seaton Donoho, “Stories and Memories of Washington,” in The Brooklyn Magazine 5 (1886), 160-161; also see Howard Dorre, "The Skinny on President John Quincy Adams's Skinny Dipping Interview," https://www.ploddingthroughthepresidents.com/2017/02/john-quincy-adams-…

- ^ John Quincy Adams, Diary 31: June 1819, in John Quincy Adams Diary: An Electronic Archive, http://www.masshist.org/jqadiaries/php/

- ^ John Quincy Adams, Diary 35: 25 August 1824, in John Quincy Adams Diary: An Electronic Archive, http://www.masshist.org/jqadiaries/php/

- ^ William M. Meigs, The Life of Charles Jared Ingersoll (Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Company, 1897), 122.

- ^ Stanley Lane-Poole, The Life of the Right Honourable Startford Canning: Viscount Stratford de Redcliffe 1 (London: Spottiswoode and Co., 1888), 321; Shannon Selin, "John Quincy Adams' Swimming Adventures," https://shannonselin.com/2017/07/john-quincy-adams-swimming/.

- ^ Elizabeth J. Clapp, A Notorious Woman: Anne Royall in Jacksonian America (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2016), 11.

- ^ Donoho, 160.

- ^ Clapp, 11.

- ^ Cynthia Earman, “An Uncommon Scold: Treasure-Talk Describes Life of Anne Royall,” The Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/loc/lcib/0001/royall.html

- ^ “7 Fun Facts About John Quincy Adams,” The New England Historical Society, https://www.newenglandhistoricalsociety.com/7-fun-facts-john-quincy-ada…

- ^ Twenty-First Annual Report of the American Scenic and Historic Preservation Society, 1916 (New York: 1916), 358.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)