In 1814, Washington Was Woefully Unprepared to Defend the Young Capital

In the weeks following the attack on the US Capitol building on January 6, 2021, as the nation tried to make sense of the insurrection that it had just collectively witnessed, experts drew comparisons between this modern mutiny and the small yet significant list of past attacks on the Capitol. The clearest comparison was that of the burning of Washington, DC by British troops in 1814. Beyond the symbolic similarities of the attacks on the seat of American democracy, perhaps the most stark parallel between the two events was the lack of proper preparations made to defend the District.

In June 1814, Albert Gallatin, an American diplomat who had been sent to London to secure peace with Great Britain in the ongoing War of 1812, wrote a cautionary letter to Secretary of State James Monroe. “The armament fitted against America will enable the British, besides providing for Canada, to land at least 15 to 20,000 men on the Atlantic coast,” Gallatin wrote, “To use their own language, they mean to inflict on America a chastisement that will teach her that war is not to be declared against Great Britain with impunity.[1]

Great Britain had recently ended a war with Napoleon’s France, signing the Treaty of Fontainebleau, which exiled the French leader to the island of Elba.[2] Gallatin had warned in a previous letter that this peace deal would free up thousands of troops and allow the country to focus its efforts and its ire on the war with America.[3] Gallatin did not specify what the “chastisement” would include but speculated that the British wished to “cripple the naval and commercial resources, as well as the growing manufactures, of the United States.[4]

President James Madison and Secretary of War John Armstrong dismissed the idea that the British would aim to attack the Capital, believing instead they would attack the nearby, wealthy port city of Baltimore. General William Winder was appointed to oversee the defense of the Capital and the surrounding area. When he took command in late June, Winder found only about 500 troops at his disposal.[5]

Madison and Armstrong maintained their belief in the safety of the District up until the British forces were reported to be moving towards the Capital city on August 23rd.[6] Armstrong ignored advice to attack the British early on in a guerrilla-style incursion and suggested to Winder to convert the Capitol building into a makeshift fortress. He recommended to Winder to “fill the upper part of the building and the adjacent buildings with infantry, regulars and militia, amounting to 5,000 men, while my 300 calvary held themselves in reserve for a charge.”[7]

The British forces, led by General Robert Ross and Rear Admiral George Cockburn, numbered only about 4,000-4,500 troops, a much smaller deployment than was anticipated by Gallatin and other British commanders.[8] Winder had assembled a sizable force of men, with historical estimates ranging from 5,500 to 7,000.[9] Despite outnumbering the British, most of the American troops were local militia forces, and only several hundred were regular military troops. The militia units consisted of able-bodied men from Maryland, Virginia, and the District. They had very little training and were ill-equipped to fight the advanced British forces.[10] Essentially the militia’s only qualifications to fight were their strength and their proximity to the battle.

Instead of ordering all of his troops into the Capitol building, Winder amassed his troops at Bladensburg, Maryland, just outside of the District. The British met the American forces--if you can call them that--at Bladensburg at midday on August 24th.[11] Madison and Monroe joined the troops and wandered the battlefield as fighting began. Their presence complicated the already difficult battle. The American President was in the line of fire, and the Secretary of State, far removed from the chain of command, ordered one of the regiments to a different position, disrupting Winder’s strategy.[12] The British quickly overpowered the Americans; some of whom quickly retreated to their homes nearby. Winder, unable to keep his troops together in a defensive position, retreated all the way west to Tenleytown.[13] The British later famously called this retreat the “Bladensburg Races.”[14] After an initial, meager show of force, the invaders now had free reign of the Capital.

The vast majority of District citizens had fled town upon hearing the news of an incoming British invasion, but at least one household stayed behind and fired a volley of shots from their house upon General Ross as he rode down the street.[15]

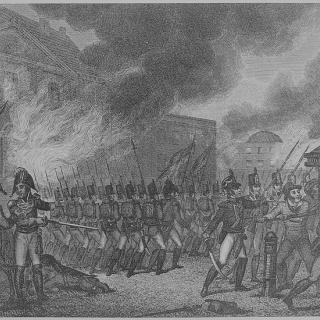

Over the next several hours, the British laid waste to the capital city. Nearly all of the government buildings were torched. Ross commanded his army to spare all private residences and property,[16] and the British carried out this order with almost surgical precision. The only exceptions to this command were the offices of the National Intelligencer, which had supposedly written unfavorable coverage of Ross and Blackburn, and the homes from which the volley of gunshots had come.[17] Notably, these two buildings formed the only two attacks against the British in the city of Washington. One attacked with guns, the other with printing presses.

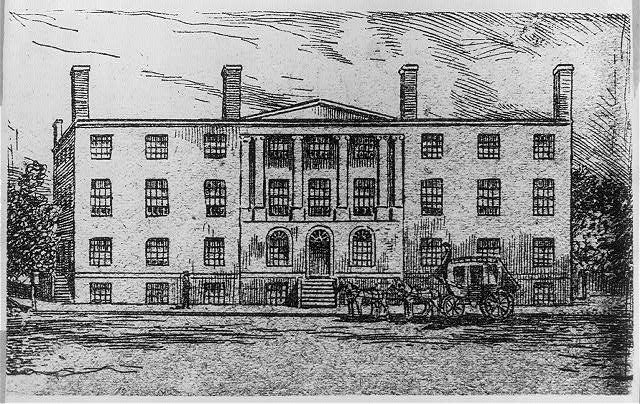

Among the only federal buildings spared from the British torch was the US Patent Office, now the site of the National Portrait Gallery. Dr. William Thornton, the architect of the US Capitol and the Superintendent of the Patent Office, reportedly convinced the invaders that the patents stored inside qualified as the private property of the inventors.[18] The destruction of the files and models would be “vandalism comparable only to the burning of the great library at Alexandria, a crime which has rung through the ages,” as one historian described Thornton’s argument.[19]

Aside from Thornton’s rescue of the Patent Office, there are several other notable anecdotes from the siege of Washington, including the infamous tale of First Lady Dolly Madison saving artifacts from the White House before she fled, but perhaps the most poignant episode in this examination of the first great attack on the US Capitol is in the moments before the seat of the US Congress and American democracy was ignited. Admiral Cockburn reportedly made his way into the House of Representatives chamber and climbed upon the Chair of the Speaker of the House, a gesture symbolic of his triumph over the Capitol. From his perch, he mockingly motioned to the assembly of British soldiers, “Shall this harbor of Yankee democracy be burned? All for it will say aye.”[20]

The British occupation of Washington did not last long. After burning much of the town on the night of the 24th, an intense storm, possibly categorized as a hurricane, in addition to the threat of an American retaliation, drove the British back to their ships in the Chesapeake Bay.[21] From there, they sailed north to attack Baltimore, fulfilling Madison and Armstrong’s prediction that the British would opt for the wealthy port city over the young capital as their target.[22] They chose all of the above.

The Americans meekly returned to their capital city. Weeks later, the House of Representatives crammed into the Patent Office building, the only federal building still standing that was large enough to accommodate the 176-member chamber.[23] A New York congressman introduced a resolution to move the capital to “a place of greater security and less inconvenience than the City of Washington.”[24] Although this attempt to move the capital eventually failed a month later, by a nine-vote margin, the question of the permanency of the District’s status as the nation’s capital wouldn’t be settled for another half century,[25] but for the time being, the Congress turned to rebuilding their city after a devastating attack.

Footnotes

- ^ The Writings of Albert Gallatin, ed. Henry Adams (Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott, 1879). 3 vols. p. 641-642

- ^ “Napoleon I: Downfall and Abdication” Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Napoleon-I/Exile-on-St-Helena

- ^ The Writings of Albert Gallatin, ed. Henry Adams (Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott, 1879). 3 vols. p. 625

- ^ Adams, p. 641-642

- ^ Forbes-Lindsay, C.H. Washington: The City and The Seat of Power. [Philadelphia: The John C. Winston Co. 1908] p. 175-182

- ^ ibid.

- ^ ibid.

- ^ McCavitt, John. “Capital Conflagrator? Major General Robert Ross” The Capitol Dome, Volume 51, no. 3. [Fall 2014]

- ^ Vergun, David. “War of 1812 Chesapeake Campaign: Large-Scale British Feint” Army.mil. September 4, 2014. https://www.army.mil/article/132855/war_of_1812_chesapeake_campaign_lar…

- ^ ibid.

- ^ Achenbach, Joel. “In 1814, British forces burned the U.S. Capitol” Washington Post. January 6, 2021. https://www.washingtonpost.com/history/2021/01/06/british-burned-capito…

- ^ ibid.

- ^ ibid.

- ^ ibid.

- ^ McCavitt, 2014.

- ^ ibid.

- ^ ibid.

- ^ “William Thornton” US Patent and Trademark Office. https://www.uspto.gov/about-us/william-thornton#:~:text=During%20the%20….

- ^ Nicolay, Helen. Our Capital on the Potomac. [New York: The Century Co. 1924] p. 107-111

- ^ McCavitt, 2014.

- ^ Shaw, Benjamin. “Fire and Rain: The Storm That Changed D.C. History” Boundary Stones. July 30, 2015. https://boundarystones.weta.org/2015/07/30/fire-and-rain-storm-changed-…

- ^ McCavitt, 2014.

- ^ “Leave No Forwarding Address: When Congress Almost Abandoned D.C.” Whereas: Stories from the People’s House. October 16, 2014. https://history.house.gov/Blog/2014/October/10-15-capitol-moving/

- ^ ibid.

- ^ ibid.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)