The Empty House that Saved the Heart of America

“You had better remove the records,” read the postscript of a letter from James Monroe to then President James Madison in 1814.1 The letter arrived at the White House as the British were marching on the city with the intent of burning it down and crushing the American spirit.2 Early on, it was clear to the people of Washington that the Army would not be able to stop the British for long. So, they started packing their wagons with whatever belongings they could fit and fled the city.

As more and more left the city, the White House and Capitol remained occupied, with government officials scrambling to prepare. In the White House first lady Dolley Madison wanted to stand her ground and stay as she had maintained she would do since the start of the war.3 With the British just outside of the District, she went as far as throwing a dinner party to show her belief that D.C. would withstand the attack, though records show that she was the only one who attended.4 Close by, less optimistic clerks of different government departments were desperately trying to get wagons and bags so they could pack up anything they could.5

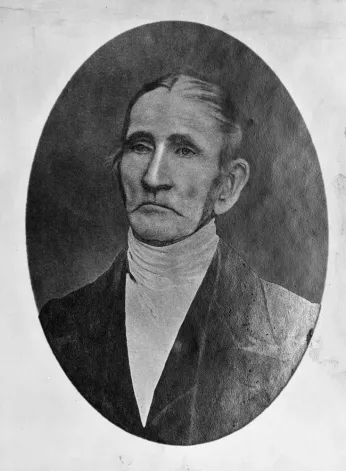

These wagons were not solely for the clerks to escape the doomed city, but to save the important documents of the Federal Government, which at the time were stored in the various locations around the city.6 As the clerks of different departments ran around D.C., failing to impound carts and grabbing what they could, John Graham, Josias King, and Stephen Pleasonton – three clerks from the State Department – set their sights on their department's archive, which housed some of the nation’s most precious records, including the Declaration of Independence, Constitution, and Bill of Rights.7 Buying up linen to make bags, the trio packed up what they could and prepared to take the records… well… somewhere.

The three documents vital to the American identity were taken out with bags of other papers and loaded onto a wagon caravan getting ready to leave the city before the British got any closer. As Stephen Pleasonton was carrying a load out, he ran into Secretary of War, John Armstrong, an encounter which Pleasonton recounted years later:

“He [Armstrong] did not think the British were serious in their intentions of coming to Washington. I replied that we were under a different belief, and let their intentions be what they might, it was the part of prudence to preserve the valuable papers of the Revolutionary Government.”8

The caravan set off to where it was initially ordered to go, an old mill near Georgetown. The mill was outside of the city and generally unassuming, a perfect place to hide the important documents. Within a few hours, the caravan had arrived at the Mill and the documents were unloaded and placed inside. With this done, the group quickly realized there was a flaw with the plan. Across the Potomac was a foundry that was supplying the Army and was a potential target for the British. The mill was just close enough that, as Pleasanton later recounted, soldiers could be “led by some evil disposed person to destroy the Mill and the papers.”9

So just as fast as they unloaded them, the clerks packed up the documents again and decided to continue west.10 As Pleasonton recalled later, “I proceeded with them to the town of Leesburg, a distance of 35 miles, at which place an empty house was procured, in which the papers were safely placed, the doors locked, and the keys given to the Rev. Mr. Littlejohn.”11 Littlejohn was a leader of the local Methodist church and had become a trusted and well liked figure.12 One of his friends, a senator, described him as someone who could “finish a saddle, preside on the bench as a magistrate, preach a funeral sermon, baptize a child, and perform a marriage ceremony, all on the same day.”13

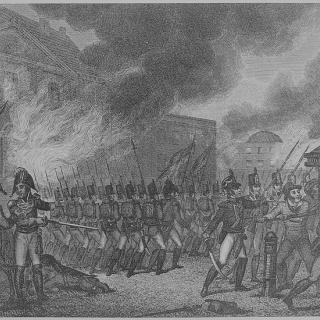

When the group finished securing the documents they retired to a nearby hotel, where some other travelers mentioned seeing D.C. in flames.14 At the Capitol, clerks of the House and Senate attempted to save what they could, but couldn’t save it all as the British lit their torches.15 Dolley Madison famously saved the portrait of George Washington, after a friend convinced her to leave.

So where, exactly, was this empty house that stored America’s founding documents? Well, a long held tradition is that the home was the Rokeby estate, which sits about three miles outside of Leesburg.16 Built in the 1760s by the first clerk of the Circuit Court of Loudoun County, Charles Binn, Sr., the Georgian home was owned by Binn’s son, William, in 1814.17 Supposedly, the documents were locked in the arched cellar of the house and, over the next several weeks, Pleasonton returned occasionally to retrieve items that the State Department needed.18 In September of 1814 the documents were retrieved from the cellar and returned to D.C., where they remain to this day.19

The Rokeby story was certainly compelling – an arched cellar on a country estate owned by a prominent local family and guarded by a do-it-all pastor has a certain appeal. So, it’s no wonder that the tale found its way into the local lore – and some published histories – of Loudoun County. For its role in protecting the most important documents in America, Rokeby has gained some recognition. In the modern day the house is privately owned and not open to the public, but one of the neighborhoods that was built on its old farmland is named after it.20

But, as local mapmaker and historian Eugene Scheel, detailed for the Washington Post in 2002, there are some reasons to doubt that the place where the documents were stored was actually Rokeby. For one, Stephen Pleasonton, despite being incredibly detailed in other parts of his account, never mentioned the Binns connection to the house, which would have been its most identifying feature at the time.21 For another, there was another likely-vacant house located much closer to Rev. Littlejohn’s parsonage in the town of Leesburg.

Regardless, Rokeby’s connection to the event seems secure in public memory. On the main road leading to the house a historic marker has been placed denoting its role in history, and it has even earned a spot on the National Register of Historic Places based at least partly on its supposed connection to America’s founding documents. But who knows? Maybe a random building in the heart of Leesburg silently holds the actual title of the house that saved the foundation of the American dream.

Footnotes

- 1

The White House Historical Association. "James Monroes Message to James Madison (White House History 35)." Accessed July 24, 2025. https://www.whitehousehistory.org/photos/photo-1-16

- 2

Kratz, Jessie. “Rescue of the Papers of the State During the Burning of Washington.” The White House Historical Association. https://www.whitehousehistory.org/rescue-of-the-papers-of-state-during-the-burning-of-washington

- 3

Fleming, Thomas. “When Dolley Madison Took Command of the White House.” Smithsonian Magazine, March 2010. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/how-dolley-madison-saved-the-day-7465218/

- 4

Fleming, Thomas. “When Dolley Madison Took Command of the White House.” Smithsonian Magazine, March 2010. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/how-dolley-madison-saved-the-day-7465218/

- 5

Kratz, Jessie. “P.S.: You Had Better Remove the Records.” National Archives. https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2014/summer/war-of-1812-save-records

- 6

Kratz, Jessie. “P.S.: You Had Better Remove the Records.” National Archives. https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2014/summer/war-of-1812-save-records

- 7

Kratz, Jessie. “Rescue of the Papers of the State During the Burning of Washington.” The White House Historical Association. https://www.whitehousehistory.org/rescue-of-the-papers-of-state-during-the-burning-of-washington

- 8

“Stephen Pleasonton Saves the State Papers.” The White House Historical Association. https://www.whitehousehistory.org/stephen-pleasonton-saves-the-state-papers

- 9

Kratz, Jessie. “Rescue of the Papers of the State During the Burning of Washington.” The White House Historical Association. https://www.whitehousehistory.org/rescue-of-the-papers-of-state-during-the-burning-of-washington

- 10

“Save the Documents!” National Park Service, May 19, 2020. https://www.nps.gov/stsp/learn/historyculture/save-the-documents.htm

- 11

Ingraham, Edward D., A sketch of the events which preceded the capture of Washington, by the British, on the twenty-fourth of August, 1814, Carey and Hart: Philadelphia, 1849: 49.

- 12

Scheel, Eugene. “In Debate About Documents’ Hiding Place, a Loudoun Legend Lives On.” The Washington Post, August 17, 2002. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/local/2002/08/18/in-debate-about-documents-hiding-place-a-loudoun-legend-lives-on/d39e399b-816c-48b7-9627-4480e4c98e73/

- 13

Scheel, Eugene. “In Debate About Documents’ Hiding Place, a Loudoun Legend Lives On.” The Washington Post, August 17, 2002. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/local/2002/08/18/in-debate-about-documents-hiding-place-a-loudoun-legend-lives-on/d39e399b-816c-48b7-9627-4480e4c98e73/

- 14

Scheel, Eugene. “In Debate About Documents’ Hiding Place, a Loudoun Legend Lives On.” The Washington Post, August 17, 2002. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/local/2002/08/18/in-debate-about-documents-hiding-place-a-loudoun-legend-lives-on/d39e399b-816c-48b7-9627-4480e4c98e73/

- 15

Kratz, Jessie. “Rescue of the Papers of the State During the Burning of Washington.” The White House Historical Association. https://www.whitehousehistory.org/rescue-of-the-papers-of-state-during-the-burning-of-washington

- 16

Scheel, Eugene. “In Debate About Documents’ Hiding Place, a Loudoun Legend Lives On.” The Washington Post, August 17, 2002. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/local/2002/08/18/in-debate-about-documents-hiding-place-a-loudoun-legend-lives-on/d39e399b-816c-48b7-9627-4480e4c98e73/

- 17

Virginia Landmark Historic Commission Staff. “Rokeby.” National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. Virginia, May 30, 1976. https://www.dhr.virginia.gov/VLR_to_transfer/PDFNoms/053-0097_Rokeby_1976_Final_Nomination.pdf

- 18

Virginia Landmark Historic Commission Staff. “Rokeby.” National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. Virginia, May 30, 1976. https://www.dhr.virginia.gov/VLR_to_transfer/PDFNoms/053-0097_Rokeby_1976_Final_Nomination.pdf

- 19

“The Declaration of Independence:A History.” National Archives. https://www.archives.gov/founding-docs/declaration-history

- 20

“About.” The Reserve at Rokeby Farm. https://rokebyfarmhoa.org/

- 21

The name Rokeby would not be given to the house until 15 years later.

Coughlan, Kathryn. "Rokeby: A Page in History." Woodbine: K&D Limited, 1992.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)