Thrice Uprooted: The U.S. Botanic Garden

In 1842, Captain Charles Wilkes returned from an expedition at sea that was marked by major gains and losses. He returned two ships poorer, had witnessed the deaths of nearly 20 men, cost the U.S. government $928,183.62, and clocked 87,000 miles on his personal odometer.[1]

That said, he also came to Washington, D.C. with the first definitive proof that Antarctica was a mass of land rather than a series of islands, with thousands of cultural artifacts from around the world, and with 10,000 plant specimens and hundreds of living plants that would become the founding collection for the United States’ oldest continuously-operating garden: The U.S. Botanic Garden.[2]

The U.S. Botanic Garden—located adjacent to the Capitol in a triangle between Maryland Ave SW, Washington Ave SW, and First Street—is rooted in the earliest planning of the capital city. Many of the Founding Fathers believed that a living repository for plants would have countless benefits, from the production of food and medicine to the scientific study of international specimens to the enjoyment of aesthetic beauty. George Washington himself wrote an impassioned letter in 1796 about how a botanic garden should be included in the city plan, even suggesting a few feasible locations.[3]

The concept gained momentum with support from the Columbian Institute for the Promotion of Arts and Sciences. One founding member, Dr. Edward Catbush, gave an address to Congress on January 11, 1817, saying: “By establishing a botanical garden, we may not only receive instruction ourselves, but excite a spirit of inquiry in the minds of the rising generation.”[4]

In 1820, the first Botanic Garden was established in Washington, D.C., located on the National Mall where the reflecting pool sits today. The swampy land was drained, and members of the Columbian Institute set out to collect plants and seeds for the garden.[5]

Unfortunately, in the following years, interest in the garden waned, funding for the project dried up, and it was abandoned in 1837. The site was left untended to be invariably overtaken by weeds.[6]

It was not until the Wilkes Expedition that the vision of a botanic garden was resurrected. In an effort to “extend the bounds of science and to promote the acquisition of knowledge,” Wilkes and his crew used cutting-edge technology to collect and record botanical materials.[7] One such device was the Wardian Case, which was a portable terrarium, that acted as a miniature protective greenhouse for plants on the go. Another was the camera lucida, which was a projection device that allowed artists to make quick renderings of objects.[8]

When Wilkes’ crew returned with a literal boatload of material—both living, pressed, and artistic—the city had to mobilize to accommodate it all. Temporarily, the collections resided in and outside of the Great Hall of the U.S. Patent Office, where the National Portrait Gallery is located today.[9] A small Gothic greenhouse was constructed, and the plants flourished under the care of the horticulturist William Brackenridge, who had accompanied Wilkes on his maritime journeys.

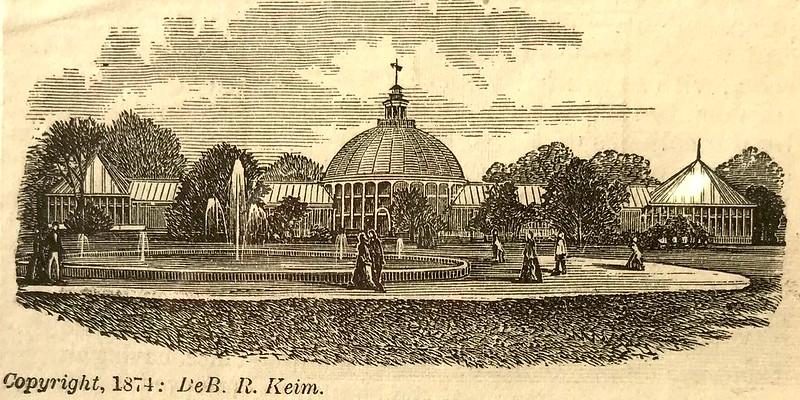

Eight years later, the garden received funding to be relocated to the foot of the Capitol; with that, the U.S. Botanic Garden was reestablished at its original site. Over the next decade, several renovations transformed the greenhouse into a Conservatory complex measuring three hundred feet long, composed of a central circular building connected to two smaller octagonal buildings.[10]

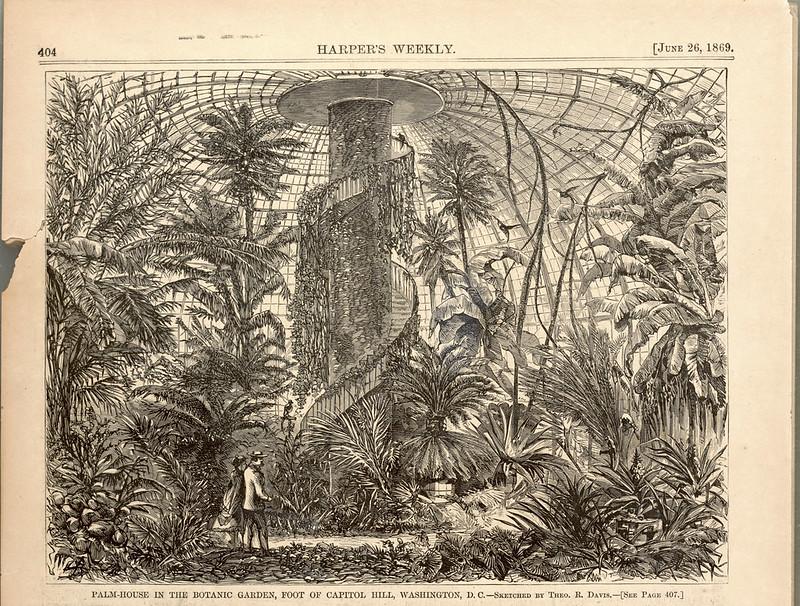

During this period, the garden was a compelling attraction in Washington, D.C., making headlines in various publications. For example, in the nationally-popular Harper’s Weekly, the Botanic Garden was featured prominently in a half-page illustration. The author made the bold statement that “There are few places in Washington city more interesting to visitors than the Botanic Garden at the foot of Capitol Hill.”[11]

In an 1891 spread in the local newspaper, The Evening Star, the author highlighted “Freaks in Plants: Wonders That May be Seen in the National Botanic Garden.”

In describing the carnivorous pitcher plant, the article paints a vivid picture, drawing an extended metaphor between the predatory plant and an alcoholic’s dependence on a “whisky shop.” As such, it frames horticulture as a topic of intrigue and wonder:

A new species of vegetable whisky shop has been added to the collection of plant curiosities at the Botanical Garden. The liquor it distills in the pitcher-shaped receptacles that hang from its stems is especially liked by frogs, which hop into these traps for the purpose of drinking it. Although the sweetish fluid is a powerful intoxicant the batrachian customer, however wildly overstimulated, would certainly jump out again were it not that two very sharp dagger-like thorns project downward from the lop of the vessel in such a manner that Mr. Frog in trying to escape is thrust through the body by them at every leap until presently he falls dead in the “liquid refreshment”—an appropriate object lesson to all intemperate creatures—whereupon the plant absorbs his substance, as the ordinary whisky shop consumes that of its frequenter, and is thus supported.[12]

The U.S. Botanic Garden relocated one final time. In 1902, the McMillan Plan was written by the Senate Park Commission, which suggested removing all of the Victorian landscaping from the National Mall, so that there would be an unobstructed view between the Capitol and the Washington Monument.[13] In 1924, the Botanic Garden was the last entity to be moved off of the National Mall. Though, it wouldn’t move far: the conservatory, plants and gardens were shifted a mere few hundred feet to the south. In 1933, it reopened to the public at the location where it has been entertaining locals and visitors ever since.

If plants could talk, what would they tell us? Staff at the Botanic Garden contend that four living plants actually trace directly back to the Wilkes Expedition: a Ferocious Blue Cycad (Encelphalartos horridus), a Queen Sago (Cycas rumphii), a Vessel Fern (Angiopteris evecta), and a Jujube (Ziziphus jujuba).[14] Would these plants agree with the human accounts that Captain Wilkes had a “complex personality,” and that he rode a fine line between being a genius and being an erratic, aloof, hot-tempered, harsh disciplinarian?[15] How does the weather compare in the U.S. capital, compared to the homelands that they left 180 years ago in Africa, New Zealand, and Asia? Was it exasperating to be uprooted a third time to be moved a block away? Regardless, the majesty of the U.S. Botanic Garden speaks for itself, and these plants have the honor of being the oldest living immigrants in Washington, D.C.

Footnotes

- ^ Karen D. Solit, “History of the United States Botanic Garden 1816-1991.” Prepared by the Architect of the Captiol under the direction of the Joint Committee on the Library of Congress. Washington, DC. https://www.usbg.gov/sites/default/files/historyoftheunitedstatesbotanicgarden1816-1991.pdf.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “The United States Botanic Garden: Establishing a Plant Collection.” United States Botanic Garden. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GPO-CDOC-109sdoc19/pdf/GPO-CDOC-109sdoc19-1-4.pdf.

- ^ “USBG at 200 (Part 1): Deeply Rooted.” United States Botanic Garden. Youtube. May 26, 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ePMb7OEaiaU.

- ^ “The United States Botanic Garden.” United States Botanic Garden.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ undefined

- ^ “The United States Botanic Garden.” United States Botanic Garden.

- ^ “Palm House Botanic Garden, Washington.” Harper’s Weekly. June 26, 1869. Internet Archive. https://archive.org/details/harpersweeklyv13bonn/page/401/mode/2up.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “Freaks in Plants,” Evening Star (Washington (DC), District of Columbia), June 27, 1891: 8. NewsBank: Access World News – Historical and Current. https://infoweb-newsbank-com.dclibrary.idm.oclc.org/apps/news/document-view?p=WORLDNEWS&docref=image/v2%3A13D5DA85AE05A305%40EANX-13EAEB84C14F7AD0%402411911-13EA4DE8C70F7AD8%407.

- ^ “USBG at 200 (Part 1): Deeply Rooted.” United States Botanic Garden. Youtube. May 26, 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ePMb7OEaiaU.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Solit, “History of the United States Botanic Garden” https://www.usbg.gov/sites/default/files/historyoftheunitedstatesbotanicgarden1816-1991.pdf.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)