Reston's Roots: Black Activism in Virginia's New Town

Around the same time that Walt Disney envisioned a futuristic alternative to urban living—EPCOT (The Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow)—a man named Robert E. Simon Jr. dreamed of a better way to live in the suburbs. It was an era of hope when many were asking: “Through careful planning, innovate design, and high ideals, can we manufacture a better way to live?”

Disney’s issues with urban environments were informed by his life in Los Angeles. He complained of noisy garbage trucks shattering the serenity of his mornings and was disillusioned with the city’s dirtiness.[1] In 1966, he released a video proposing a “City of Tomorrow,” a climate-controlled, pedestrian-oriented working community for people employed by the Walt Disney Company in Florida. “I believe we can build a community that more people will talk about and come to look at than any other area of the world,” said Disney.[2] However, his dreams went to bed when he died a few months after the release of the video. Epcot (no longer an acronym) opened its doors in October of 1982—a theme park rather than a whole new world.

Simon’s disappointments were centered around New York City suburbs. Simon was a native New Yorker, the son of Jewish immigrants from Germany, and the heir to a multi-million-dollar real estate investment business with clients like Carnegie Hall.[3] After serving in the Second World War, he left Manhattan with his wife and two children to live in Syosset, Long Island. The post-war Baby Boom saw many families making a similar decision, fleeing cities for suburbia. Homogenous tract houses promised more room for families to grow. The problem was, Simon hated suburban living. Suburbia lacked entertainment, and sprawl demanded an inconvenient reliance on cars.[4]

So, my dear Boundary Stones reader, what does a Northeastern millionaire have to do with the D.C. metropolitan area? Hold your horses, local history enthusiasts!

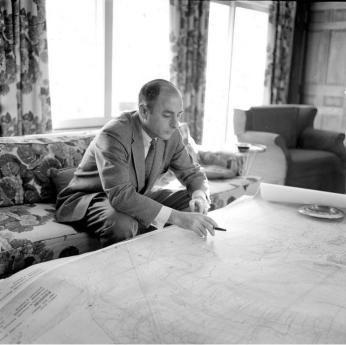

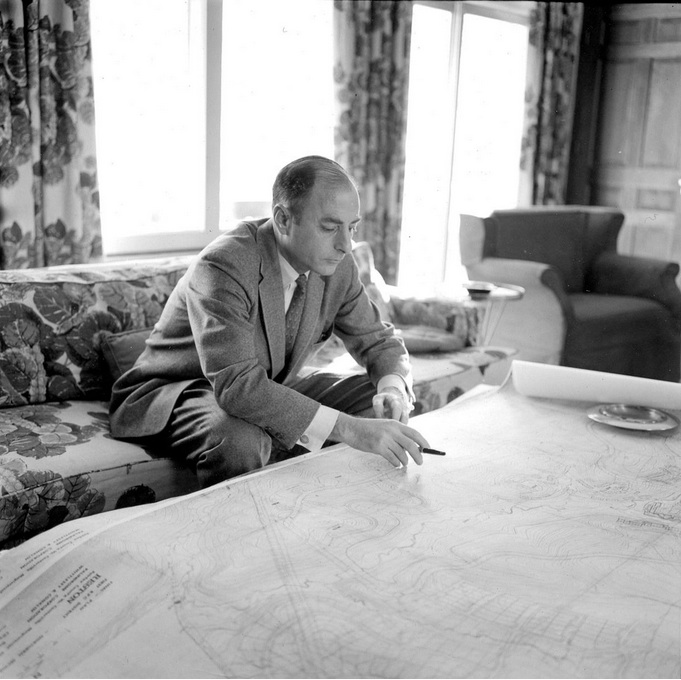

In 1961, a broker approached Simon with an opportunity: nearly 7,000 acres of land for sale in Northern Virginia’s Fairfax County.[5] What Simon lacked in city planning expertise, he compensated with vision, ideals, and seed funding. Simon dreamed of “a humanistic alternative to the isolation and anonymity of conventional suburbia, a triumph over the doldrums of cookie-cutter tract homes.”[6]

Simon bought the land, and the seeds of a new city took root. Its name would draw upon his own initials “R. E. S.”—Reston, Virginia.

Over the following years, Reston would be the subject of much careful thought and planning. The Reston Master Plan was finished in 1962, written by Simon and the architectural firm, Whittlesey & Conklin. The plan outlined lofty ideals that hoped to address “the human requirements of our civilization.”[7] It envisioned 75,000 Restonians by 1980, who would reap the benefits of the following seven principles:[8]

- Reston would have housing for all.

- Reston would allow residents to “Live, Work & Play” in the same community.

- Reston would put the importance and dignity of each individual as the focal point of planning.

- Reston would be beautiful–nature would be fostered.

- Reston would accommodate leisure time.

- Reston would have amenities from the outset including a library, golf courses, art, and more.

- Reston would be financially successful.[9]

On December 4, 1965, the new town celebrated its grand opening. An article was published on the front page of the New York Times, describing “a brave and deliberate design to create a community out of whole cloth” that “looks like an attractive cross between an updated Georgetown and an Italian harbor town like Portofino.”[10]

Reston was not the only new city from this time period, but one feature made it distinctly American: unlike examples in Europe—like Vällingby, Sweden and Tapiola, Finland—Reston did not enjoy any government sponsorship.[11] It was completely privately funded. An experiment in free enterprise.

And for many, Reston was a tough sell. One reporter found that more than 70 prospective funders declined Simon’s proposal due to insurmountable “deviations from the norm.”[12]

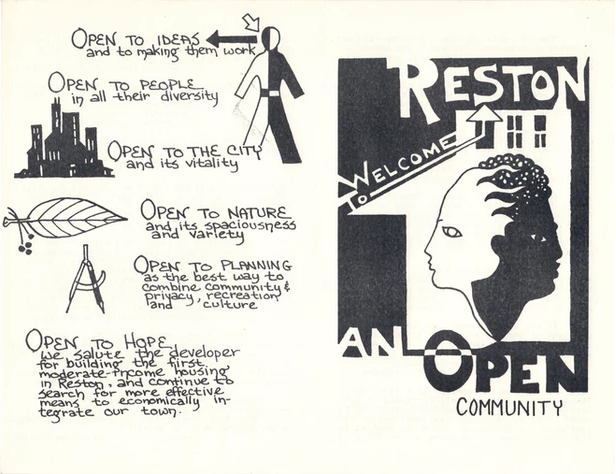

One of the most crucial deviations centered around race—call it “open,” “integrated” or “desegregated,” Reston would not ban Black homeowners from moving in. Three years prior to the Civil Rights Act, and located in the South, this was out of the ordinary.

Simon did not want his new town to reflect the racially homogenous suburbs that were created by the era White Flight in response to the Great Migration. Between 1910-1970, millions of Black Americans headed northward to escape the Jim Crow South. The majority settled in cities in the North and West. As one study put it: “for every Black person to arrive in the city, a White family left.”[13]

In his biography, Simon explains his dream for Reston: a town that accepted people of all races and socioeconomic backgrounds.

“The idea of community means people of all incomes and races living happily together … We were turned down by 50 banks for normal construction loans. The backers we did have were shocked and considered walking away from this thing. We publicized that it was an open community.”[14]

Simon made an official commitment to racial diversity when he sold a plot of land to Edward E. Mitchell, a retired Army colonel working in Defense Secretary Robert McNamara’s office.[15]

One year after the first families moved into Reston, an article in Ebony Magazine reflected on how the new, integrated city was faring. It reported that of the 1,100 people living in Reston, there were only five Black families by December 1966.[16] However, there was some room for optimism that Reston could eventually grow into the diverse community that Simon had promoted. As Taylor Williams, a high school principal who was one of Reston’s first African American residents, remarked: “You don’t identify in racial terms out here. You’re just an individual. You’re either a gentleman or a lady and that’s it. They make you feel a part, like you’re in a democracy or something.”[17]

The reporter cited the majority liberal population for the apparent lack of racial prejudice in Reston, but still noted that cost was a major barrier to entry for most Black Americans.

The fate of Reston’s ideals was cast into question when the town shifted from one man’s dream to a corporate subsidiary. In 1967, Simon signed an agreement with one of Reston’s primary investors, the Gulf Oil Corporation, to create Gulf-Reston, Inc.[18] Over the following years, Gulf Oil took more and more control of the town’s direction, and by 1969, the town’s namesake was fired for conflicting interests.[19] During these years, journalists and residents kept a watchful eye on the city, curious to evaluate whether the town’s corporate owner would uphold the social philosophies envisioned by Simon.

By 1969, there were approximately 70 Black families in Reston—roughly 3% of the population.[20] That same year, a group of community members banded together to form Reston Black Focus, a committee dedicated to advocating for Black rights and culture in Reston.[21]

The Reston Black Focus Goals Document outlined why a new city posed a special opportunity to address issues deeper than the general malaise of suburbia:

A new town is special to a Black man. We support the Reston concept: a diverse integrated community where men can comfortably and meaningfully live, work and raise families … Black people must be able to look to ‘new towns’ for housing, schooling and recreational facilities unencumbered by the built in racism prevalent in ‘old’ urban and suburban systems.[22]

In an article published in the Reston Times, entitled “New Town: Black Man’s Hope,” the research engineer Edward G. Sharp outlined specific measures that Reston must take if its ideals were to serve residents of every race. Just like Simon outlined the key philosophical points that would make Reston unique, Sharp added the following points to the conversation:

“An integrated, vital community cannot exist unless the basic humanness and intrinsic worth of each individual in the community is implicit in all the community’s institutions. Black families in comfortable housing are not enough if:

- The community accepts only Black individuals who have “White” attitudes, tastes, and values

- Construction projects use Black men only for certain kinds of jobs

- The advertising and sales promotion accent plantation living

- The schools and libraries present only “White” history, music, art and literature

- Low and moderate income Blacks don’t fit into the scheme of things.”[23]

Journalist Wolf Von Eckardt explored the issues of “Real Life” facing Reston in a 1969 Washington Post article. He highlighted some of the practical requests of Reston Black Focus, such as representation in the city’s marketing materials, and the hiring of Black realtors to encourage sales to Black homeowners.

Glenn W. Saunders, VP of Gulf Oil, pushed back against the requests of Black Restonians, claiming that such measures would be “impractical” because they already employed too many salesmen. When asked, Simon also admitted that he would not prioritize racial integration in Reston’s marketing.[24]

Von Eckardt remarked: “But the question is not, it would seem, Glenn Saunders’ or Bob Simon’s personal views or integrity. It is whether free enterprise alone can be relied upon to set America straight.”[25]

So, did free enterprise set America straight?

History suggests not, though Reston continued to have a non-zero Black population. By 1985, 10% of the 41,000 residents were Black.[26] Today, with a population of 61,000 the Black population has flatlined at 10%, with White residents making up 72%, an Asian population of 10%, and roughly 5% identifying as two or more races. A 2019 Washingtonian article deemed Reston as “whiter, older, and richer than its founder ever intended.”[27]

In the mid-1960s, Robert E. Simon said: “The planners of Reston were neither arrogant nor presumptuous enough to conceive of their task as the building of a utopia, [but] it was and is hoped that something a little closer to the heart’s desire than is now available for most people would be made possible.”[28]

In many ways, Reston did achieve this humble goal. Nevertheless, local Black activists were quick to point out that urban planners must take more novel, radical procedures if the city was to approach anywhere near a utopia.

Footnotes

- ^ Matty Merritt. “A brief history of EPCOT: Walt Disney’s failed city of tomorrow.” October 1, 2021. https://www.morningbrew.com/daily/stories/2021/10/01/a-brief-history-of….

- ^ “Walt Disney’s E.P.C.O.T. film (1966) – The Project.” Youtube. May 8, 2014. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r9d2FEAR2t4.

- ^ “A Brief History of Reston Virginia.” Reston Museum. https://www.restonmuseum.org/restonhistory

- ^ Tom Grubisich. “Reston, Virginia.” Encyclopedia Virginia. https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/reston-virginia/#:~:text=Found….

- ^ “A Brief History of Reston Virginia.” Reston Museum.

- ^ Special to the New York Times. "RESTON, VA., AT 20: IDEALS AND DANGER?" New York Times, May 21, 1985, Late Edition (East Coast). https://www.proquest.com/newspapers/reston-va-at-20-ideals-danger/docvi….

- ^ Simon Enterprises, Whittlesey & Conklin. “Reston Master Plan.” May 1962. https://www.restonmuseum.org/_files/ugd/e7f463_fce86581f6e44faeb107eb16….

- ^ “The Reston Story” https://www.restonmuseum.org/_files/ugd/e7f463_beaf8da4e9064565a2872631…;

- ^ “A Brief History of Reston Virginia.” Reston Museum.

- ^ Ada Louise Huxtable. Special to The New York Times. 1965. "Fully Planned Town Opens in Virginia: The Totally Planned Community of Reston, Va., is Dedicated with 'Salute to Arts' TOWN IS CALLED 'A BRAVE DESIGN' Heckscher Notes it was the Dream of One Developer -- Striking Features seen." New York Times (1923-), Dec 05, 1. https://www-proquest-com.dclibrary.idm.oclc.org/historical-newspapers/f….

- ^ Ada Louise Huxtable. "A Crucial Test for American Town Planning." New York Times (1923-), Sep 25, 1967. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/crucial-test-american-to….

- ^ Ada Louise Huxtable. Special to The New York Times. 1965. "Fully Planned Town Opens in Virginia.”

- ^ Christopher Muscato. “Impact of White Flight on the Civil Rights Movement.” Study.com. https://study.com/academy/lesson/impact-of-white-flight-on-the-civil-ri…

- ^ Alcorn, Kristina S. In His Own Words: Stories From the Extraordinary Life of Robert E. Simon Jr. Great Owl Books. (2016). P 83.

- ^ Ebony Magazine, “Reston, VA: New Design for an Ideal City.” December 1966. https://books.google.com/books?id=_5q3AoSbTGAC&printsec=frontcover&sour….

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ada Louise Huxtable. "A Crucial Test for American Town Planning." New York Times.

- ^ “A Brief History of Reston Virginia.” Reston Museum.

- ^ Thomas Grubisich. "Focus on Black Culture: Black Culture." The Washington Post, Times Herald (1959-1973), Sep 01, 1969. https://www-proquest-com.dclibrary.idm.oclc.org/historical-newspapers/f….

- ^ Eil and Mona Blake; Ed and Beverly Sharp; Rodney Smith. “Reston Black Focus: Goals Document.” George Mason University Libraries. April 25, 1969. http://mars.gmu.edu/bitstream/handle/1920/9294/C0137B01F048.pdf?sequenc….

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Edward G. Sharp, “Reston-Special To Black Men.” George Mason University Libraries. 1969. http://mars.gmu.edu/handle/1920/9594.

- ^ Wolf, Von Eckardt. "The 'Real Life' Takes Over in Secluded Reston: Cityscape." The Washington Post, Times Herald (1959-1973), Jul 20, 1969. https://www-proquest-com.dclibrary.idm.oclc.org/historical-newspapers/r….

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Special to the New York Times. "RESTON, VA., AT 20: IDEALS AND DANGER?"

- ^ Benjamin Wofford. “The Very Uncivil War Going Down in America’s Most Civil Suburb.” Washingtonian. Dec 15, 2019. https://www.washingtonian.com/2019/12/15/very-uncivil-war-reston-americ….

- ^ Tom Grubisich. “Reston, Virginia.” Encyclopedia Virginia.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)