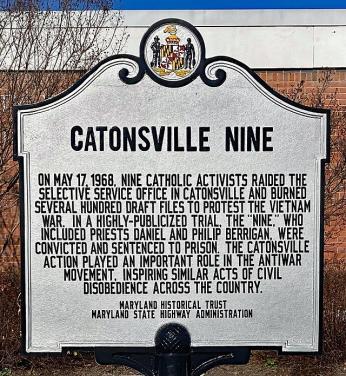

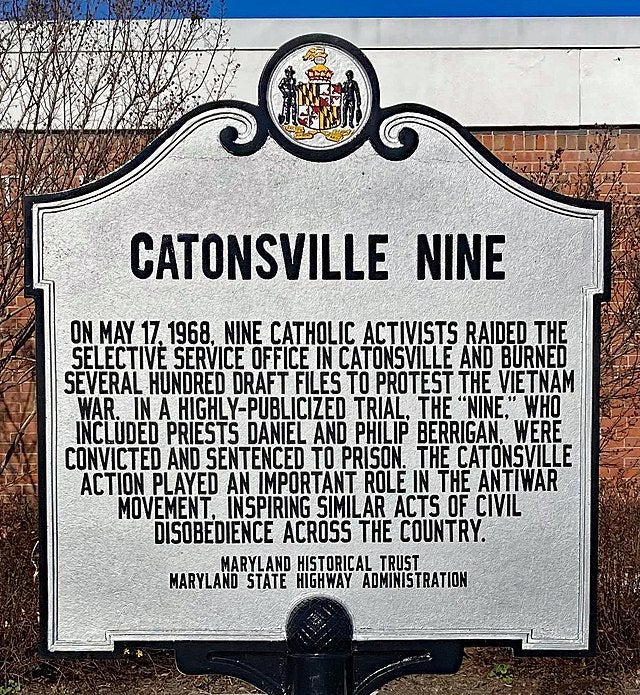

The Burning of Paper, Not Children: A Look at the Catonsville Nine

On October 17, 1967, four men entered the Baltimore Selective Service Offices, hiding Mr. Clean bottles filled with blood beneath their coats. They strolled by employees who were none the wiser to what was going to happen next. In an instant, the visitors began grabbing draft files from shelves and defacing them with blood. They were quickly arrested, but not before they succeeded in damaging hundreds of records.[1]

In a press statement, the men – two Catholics and two Protestants who became known as the Baltimore Four – revealed that they were driven by their faith to protest the Vietnam War. “We shed our blood willingly and gratefully…We pour it upon these files to illustrate that with them and with these offices begins the pitiful waste of American and Vietnamese blood ten thousand miles away.”[2]

It would not be the last such action. And, in fact, the subsequent trial provided a important detail that would shape future protests. When asked why the marring of the draft files was so devastating, the government revealed that there were no duplicates–if the files were destroyed, that person would no longer exist in the eyes of the government.[3] George Mische, peace movement organizer and US army veteran, remembered turning to his wife Helene Mische while sitting in the gallery at the trial of the Baltimore Four and saying: “We’re going to burn the goddamn things.”[4]

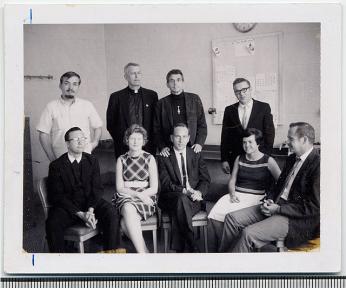

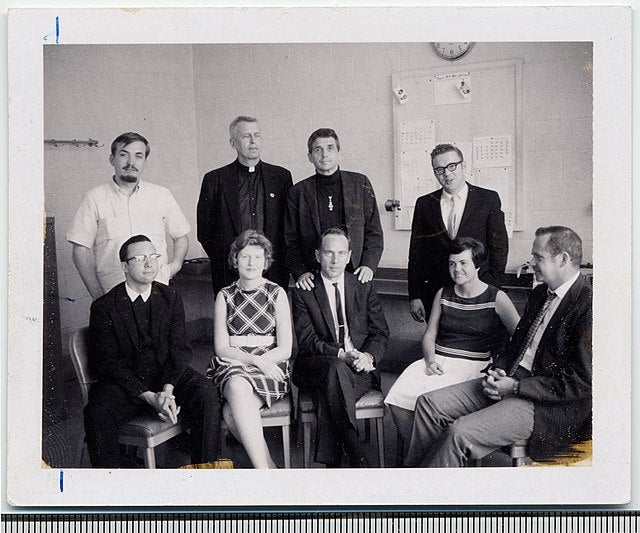

Mische, along with Father Philip Berrigan and artist Tom Lewis (two of the men from the Baltimore Four action) gathered in a peace action house in Washington D.C. soon after the conclusion of the Baltimore Four trial. The house was opened by the Misches soon after they married in 1967.[5] They were joined by:

- Marjorie “Margarita” Melville, former nun inspired by her experiences as a Maryknoll missionary in Guatemala

- Her husband, Tom Melville, former priest, and Maryknoll missionary in Guatemala

- John Hogan, another former Maryknoll missionary in Guatemala

- Brother David Darst, who volunteered after the Baltimore Four action and later said: “I wanted to do a tiny bit to stop the machine of death I saw moving.”[6]

- Registered nurse and civil rights activist Mary Moylan, who Mische described as wanting: “…to show that women should be on equal footing as men.”[7]

Berrigan, who had been a priest at Baltimore’s St. Peter Claver’s Church since 1965, knew the area quite well as did Baltimore native Moylan and Maryland-born Lewis. The eight of them, along with other volunteers, cased every draft board in the Baltimore area. They ended up choosing Catonsville, a small, sleepy suburb of Baltimore. They chose it for its sleepiness, as it decreased the possibility of anyone getting hurt, and there were no armed guards outside of the office.[8] Furthermore, the Selective Services Office in Catonsville was housed in a Knights of Columbus building.

The Knights of Columbus are a global Catholic fraternal service order, with membership limited to practicing Catholic men. During the 1960s, the Knights of Columbus were supportive of the Vietnam War, a norm amongst Catholic organizations.[9] Mische explained: “Our being Catholic was important because at that time, only five of more than 400 U.S. bishops were speaking out against the war…As Catholics, we needed to show that we didn't agree with the hierarchy of the church.”[10]

In the basement of Mische’s house in D.C., support team members Bill O’Connors and Dean Pappas concocted homemade napalm using Ivory soap flakes and gasoline, a recipe that came straight from the US Special Forces handbook.[11] “We use napalm on these draft records because napalm has burned people to death in Vietnam,” the group would explain later.[12]

With the location chosen and the napalm made, the eight of them selected May 17 as the day of action. The day before, Philip Berrigan traveled to Cornell University where his brother, Jesuit priest Daniel Berrigan, worked and informed him of the plan.[13] Daniel, who had previously traveled to North Vietnam with historian Dr. Howard Zinn to escort three American prisoners of war home, was inspired to join his brother as the final member of the group.[14] Soon the world would know them as the Catonsville Nine.

On the day of the action activist Brendan Walsh, who would later go on to found soup kitchen Viva House in Baltimore, drove the nine to the draft board office in St. Peter Claver’s parish van.[15] Both Berrigan brothers wore clerical robes, and the rest of the nine were dressed nicely as well. It was all part of the plan as Baltimore Sun reporter Christina Tkacik noted later: “While antiwar protesters of the 1960s were dismissed as "longhairs" and hippies, the Catonsville Nine wanted to present an image that wouldn't be written off so easily. They were all clean-cut.”[16] Mische added: “We figured the media would really be more apt to take a look at this if we weren't in the same mold of the protesters of the campus world.”[17]

After exiting the van, the nine of them marched into the office where two female clerks, Mary E. Murphy and Phyllis S. Morsberger worked, unaware of what was about to happen. While Moylan and Margarita Melville kept the two clerks from calling for help, the others gathered up 378 1-A draft files. Those files represented the lives of young men most likely to be sent to fight in Vietnam. Darst stood at the door, operating as the lookout.[18]

“I was beside myself. I didn’t know what to do,” recalled Murphy, one of the clerks, in a later interview.[19]

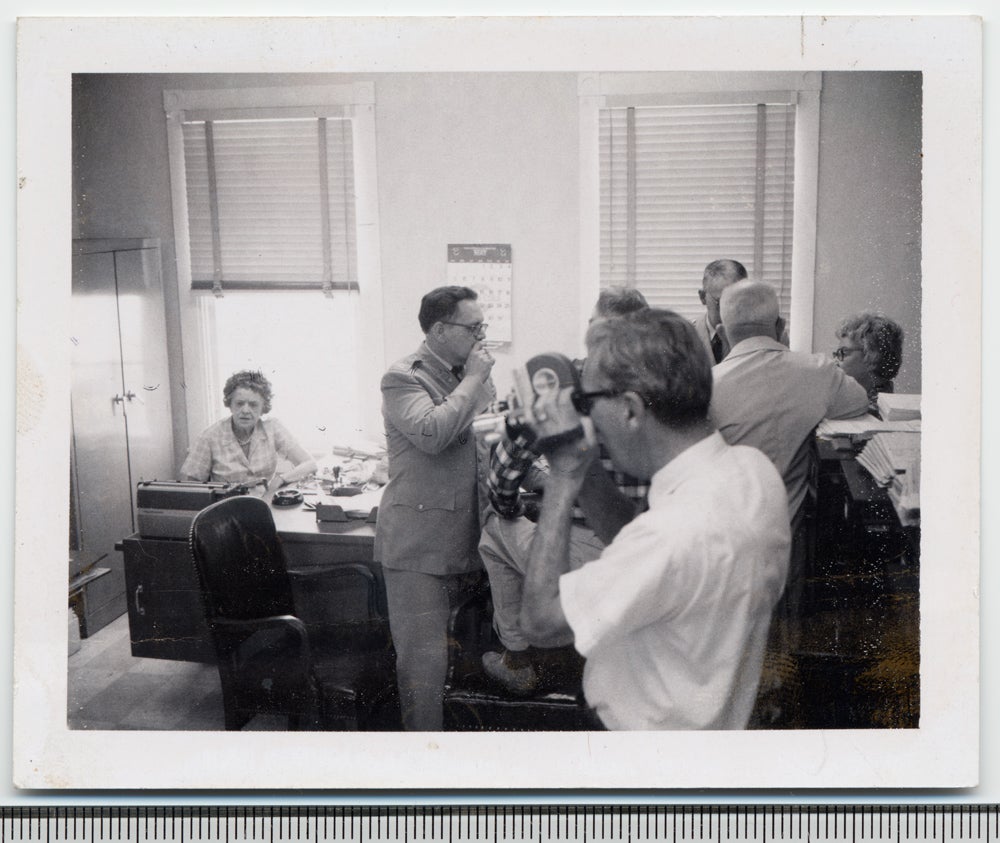

Boxes in hand, the nine left the office, walking down to the parking lot below the building, where they dumped the files on the ground. WBAL-TV reporter Pat McGrath, along with cameraman Bob Boyer and soundman Ed Smith arrived on the scene just as the draft files were doused with the homemade napalm.[20] The nine all carried matches with them, and starting with Hogan, lit draft files aflame. It was a powerful image, the nine of them standing in a semi-circle, saying the Lord’s Prayer as the documents holding the lives of hundreds of young men burned before them.[21]

“We have chosen to be powerless criminals in a time of criminal power. We have chosen to be branded as peace criminals by war criminals.” Daniel Berrigan said as he and the rest of the Nine stood, watching the files turn to ash.[22]

While they waited for the police to arrive, Tom Melville spoke about the group’s motivations. “Our church has failed to act officially, and we feel that as individuals we are going to have to speak out in the name of Catholicism and Christianity and we hope by our action to inspire other people who have Christian principles or a faith similar to Christianity will act accordingly to stop the terrible destruction that America is wrecking on the whole world.”[23]

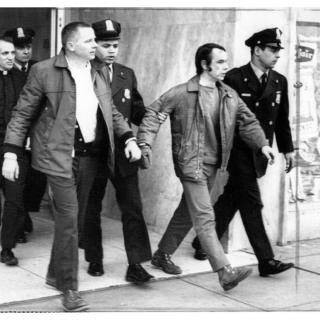

After firefighters and police arrived on the scene, the nine climbed into the back of the police wagon and rode to the station. Word of the action spread, with the public latching onto the Berrigan brothers.[24] The idea of two Catholic priests burning draft files to protest the Vietnam War captivated audiences around the world. Suddenly, the sleepy town of Catonsville was the center of the antiwar movement.

On Monday, October 5, 1968, the group stood trial on charges of conspiracy, damaging government records, illegally removing records and hindering the work of government employees. Outside the courthouse, which was housed inside the post office in downtown Baltimore, thousands of people gathered.[25]

Two supporters, Christian Brothers Timothy Diugos and Peter McKeon wrote in an open letter to the Baltimore Sun: “As citizens and as Christians, we fully support the Catonsville Nine, both in the sentiments they expressed and the methods they used.”[26] Though a minority in the Christian community, which largely denounced the actions of the Nine, their words reflected the thoughts of many of the supporters who showed up during the four-day trial. “Five months ago, nine Catholic Christians stood up in the midst of the tide of violence and death and bravely chose life.”[27]

Inside the courtroom, 150 people squished into the seats, while 60 more people milled about the lobby trying to get into the courtroom. When the defendants entered, the audience gave them a minute-long ovation. In a surprising move, the nine chose not to participate in the selection of a jury.[28] The attorney heading their defense, activist William Kunstler, explained: “The defendants say that they do not have faith in the judicial process. They want nothing to do with the selection of the jury because they do not recognize this court as a forum in which the matter can be solved.”[29]

That night, around 1,000 people gathered in the hall of St. Ignatius Roman Catholic Church for a rally organized by local peace movements. Many came from out of town and several national leaders spoke in support of the nine, including founder of the Catholic Workers Movement Dorothy Day, Reverend James A. Pike, philosopher Noam Chomsky, and theologian Harvey Cox.[30]

Over the next three days, the defense presented no witnesses, instead letting each of the Nine speak to their motivations. One after the other, they addressed the court, often invoking their faith. Father Daniel Berrigan’s testimony stood out. “Our apologies, dear friends, for the fracture of good order, the burning of paper instead of children, the anger of the orderlies in the front parlor of the charnel house. We could not, so help us God, do otherwise.”[31]

In his testimony, Mische detailed: “This society is getting all up tight about burning 378 pieces of paper or whatever it was. Every day they’re putting napalm on people and burning them to death.”[32] The prosecution brought forth the two female officer workers, who both testified that they had been “manhandled” by Moylan and Margarita Melville.[33]

On October 10, the final day of the trial, a remarkable scene unfolded. Father Daniel Berrigan stood up and asked presiding Judge Roszel Thomsen if the court could stand for the Lord’s Prayer. Thomsen responded that government prosecutors would have to agree, but he had no issue with it.[34]

When federal prosecutor Steven M. Sachs informed the court that the government approved the request, each person stood up and said the Lord’s Prayer in unison. Clerk Donald K. Joseph described what he witnessed: “The scene, unprecedented before or after, just before the rendering of the obvious verdict of guilty, of an entire courtroom standing to say the Lord’s Prayer.”[35] After that, the jury convened for an hour and 20 minutes before returning with a guilty verdict.

The night before the sentencing a few weeks later, 150 supporters held an all-night vigil in hopes of a light sentence.[36] Though the case had been decided, Kunstler continued to argue that the jury should have been instructed in the rare concept known as jury nullification. “Juries can nullify those laws that affront their consciences,” he told the court as an aide distributed copies of Kunstler’s whole argument to the press.[37]

In another unusual move, Judge Thomsen directed his assistant to follow suit.[38] A section of Thomsen’s argument stated: “No matter how important you believe peace to be, none of us can have the freedom guaranteed to us by our Constitution unless the people who disagree with the policy of our Government express their disagreement by legal means rather than by violation of the law.”[39]

Though Thomsen repeatedly emphasized his respect for the sincerity of the Nine’s motives, his belief in the law held firm. Each of Nine faced up to 3 ½ years in prison depending on their role in the Catonsville draft office action. The ruling determined that Philip Berrigan and Tom Lewis, who already had 6-year sentences due to their involvement in the Baltimore Four action, would serve their sentences concurrently. It was among the longest terms handed to clergymen for protest activities in the US.[40]

The defense for the Catonsville Nine and the Baltimore Four appealed the verdicts in 1969. They argued that the protest motive had been ‘muzzled’ by an improper court ruling. Again, the issue of jury nullification took center stage. Kunstler and Fred E. Weisgal, primary attorney for the Baltimore Four, argued that the juries had been prevented from seeing the “higher purpose of the protest” because the court had failed to provide proper instruction.[41] Paraphrasing Kunstler’s argument, Baltimore Sun reporter Theodore Hendricks summarized the issue for readers: “The jury should be told that it can consider whether the defendants ‘did the right thing,’…. In such cases, the jury becomes an ‘escape valve’ and a barometer of public sentiment. If someone is found innocent in such a case, the jury would thus agree that his motives were good but the law bad.”[42] Despite their best efforts, the appeal failed.

Moylan, both Berrigans, and Mische chose to go underground instead of facing their time. The Melvilles, Lewis, and Hogan went to jail. Tragically, Darst died in a car accident before he was set to serve his time.[43] Though the Berrigans and Mische were all caught relatively quickly, Moylan stayed underground for nine years. She surrendered by choice in June 1979, when she surfaced in Baltimore and contacted defense attorney Harold Buchanan to negotiate the terms of her surrender.[44]

Despite the fact that their legal defense was unsuccessful, the Catonsville Nine helped inspire hundreds of subsequent protest actions, which targeted draft boards and other sites such as the Dow Chemical Offices in downtown DC. By the time the draft ended in 1973, Mische estimated that 3-4 million draft files were destroyed, each representing the life of a man.[45]

As he reflected later, “Despite what people may think, we were ordinary people who wanted to prove that even small numbers of people could make a difference.”[46]

Footnotes

- ^ Digital Maryland, “Resistance,” Fire and Faith: The Catonsville Nine File, Enoch Pratt Free Library, accessed May 24, 2022, http://c9.digitalmaryland.org/page.php?ID=3.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Francis X. Clines, “Catonsville Journal; Keeping Alive the Spirit of Vietnam War Protest,” The New York Times, published May 3, 2001, https://www.nytimes.com/2001/05/03/us/catonsville-journal-keeping-alive….

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ George Mische, “Inattention to accuracy about 'Catonsville Nine' distorts history,” National Catholic Reporter, The National Catholic Reporter Publishing Company, published May 17, 2013, https://www.ncronline.org/news/justice/inattention-accuracy-about-caton….

- ^ Hendricks, Theodore W. 1968. One of Catonsville 'nine' admits he was lookout: James Darst says he wanted to raise outcry on war. The Sun (1837-), Oct 09, 1968. http://proxygw.wrlc.org/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/historical-n… (accessed June 1, 2022).

- ^ Mische, “Inattention to accuracy about 'Catonsville Nine' distorts history.”

- ^ John Lingan, “'SICK AT HEART': THE LONELY RADICALISM OF THE CATONSVILLE NINE,” Pacific Standard, The Arena Group, last updated May 3, 2017, https://psmag.com/news/radical-patriotism-the-catonville-nine.

- ^ Mische, “Inattention to accuracy about ‘Catonsville Nine’ distorts history.”

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Digital Maryland, “The Action,” Fire and Faith: The Catonsville Nine File, Enoch Pratt Free Library, accessed May 24, 2022, http://c9.digitalmaryland.org/page.php?ID=2.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Digital Maryland, “Profiles,” Fire and Faith: The Catonsville Nine File, Enoch Pratt Free Library, accessed May 24, 2022, http://c9.digitalmaryland.org/page.php?ID=36.

- ^ Christina Tkacik, “Fifty Years Later, Catonsville Nine draft protest inspires activists, angers opponents,” Baltimore Sun, Baltimore Sun, published May 19, 2018, https://www.baltimoresun.com/maryland/baltimore-county/bs-md-catonsvill….

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Digital Maryland, “Action.”

- ^ Mary E. Murphy, “Burning of draft board records by Philip and Daniel Berrigan and others, May 17, 1968: an interview with Mary E. Murphy given on November 2, 1972,” interview by Jean Walsh, accessed May 24, 2022, http://c9.digitalmaryland.org/artifact.php?ID=CLCN100.

- ^ Jake Olzen, “How the Catonsville Nine survived on film,” Waging Nonviolence, Waging Nonviolence, Published May 17, 2013, https://wagingnonviolence.org/2013/05/how-the-catonsville-nine-survived….

- ^ Wagingnonviolence, “The Catonsville Nine original 5/17/68 footage,” YouTube Video, 9:17, May 17, 2013, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d3NM3xaNuLk.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Fern Shen, “A fiery act of civil disobedience in Catonsville still resonates, 45 years later,” Baltimore Brew, published May 1, 2013, https://www.baltimorebrew.com/2013/05/01/a-fiery-act-of-civil-disobedie….

- ^ Digital Maryland, “The Street,” Fire and Faith: The Catonsville Nine File, Enoch Pratt Free Library, Accessed May 24, 2022, http://c9.digitalmaryland.org/page.php?ID=22.

- ^ Timothy, Diugos and Peter McKeon. 1968. “Support for the 'Catonsville nine'.” The Sun (1837-), Oct 16, 1968. http://proxygw.wrlc.org/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/historical-n… (accessed June 10, 2022).

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ DEIRDRE CARMODY Special to The New York Times. 1968. “9 WAR FOES BEGIN BALTIMORE TRIAL: 1,500 SUPPORTERS HECKLED AS THEY STAGE A MARCH.” New York Times (1923-), Oct 08, 1968. http://proxygw.wrlc.org/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/historical-n… (accessed June 10, 2022).

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Digital Maryland, “The Courtroom,” Fire and Faith: The Catonsville Nine File, Enoch Pratt Free Library, accessed May 24, 2022, http://c9.digitalmaryland.org/page.php?ID=23.

- ^ Bart Barnes Washington Post, Staff Writer. 1968. “Catonsville 9 defend burning draft files.” The Washington Post, Times Herald (1959-1973), Oct 10, 1968. http://proxygw.wrlc.org/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.proxygw.wrlc… (accessed June 10, 2022).

- ^ Hendricks, “Lookout.”

- ^ ZION, SIDNEY E. 1968. “Law: Another 'no' to a challenge on the Vietnam war.” New York Times (1923-), Oct 13, 1968. http://proxygw.wrlc.org/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.proxygw.wrlc… (accessed June 10, 2022).

- ^ Robert A Erlandson, Staff Writer. 1993. “Moral passion still burns among 'Catonsville nine': 6 to mark protest's 25th anniversary”. The Sun (1837-), May 17, 1993. http://proxygw.wrlc.org/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/historical-n… (accessed June 1, 2022).

- ^ Bart Barnes Washington Post, Staff Writer. 1968. “Nine jailed for burning draft files: Catonsville nine get terms for burning draft records.” The Washington Post, Times Herald (1959-1973), Nov 09, 1968. http://proxygw.wrlc.org/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.proxygw.wrlc… (accessed June 22, 2022).

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Hendricks, Theodore W. 1969. “DRAFT FILE BURNERS ASK FOR RETRIAL: CATONSVILLE NINE CLAIM COURT STIFLED THEIR PROTEST MOTIVE.” The Sun (1837-), Jun 11, 1969. http://proxygw.wrlc.org/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/historical-n… (accessed June 10, 2022).

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Digital Maryland, “The Verdict,” Fire and Faith: The Catonsville Nine Files, Enoch Pratt Free Library, accessed May 24, 2022, http://c9.digitalmaryland.org/page.php?ID=25

- ^ Lyons, Sheridan. 1979. “Catonsville 9 fugitive ends 9-year run.” The Sun (1837-), Jun 20, 1979. http://proxygw.wrlc.org/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/historical-n… (accessed June 10, 2022).

- ^ Shen, “Civil disobedience.”

- ^ Mische, “Inattention to accuracy about ‘Catonsville Nine’ distorts history.”

![Hundreds of draft protestors stand outside the courthouse where the trial of the Catonsville Nine takes place, peace signs up in support of the Nine. (Source: William Morgenstern, [War and draft protest], 1968. Gelatin silver print. University Archives, University of Maryland, Baltimore County, UARC Photos-09-01-0025.)](/sites/default/files/styles/embed/public/street-rally-s_0.jpg?itok=7GSdtlKF)

![Hundreds of draft protestors stand outside the courthouse where the trial of the Catonsville Nine takes place, peace signs up in support of the Nine. (Source: William Morgenstern, [War and draft protest], 1968. Gelatin silver print. University Archives, University of Maryland, Baltimore County, UARC Photos-09-01-0025.)](/sites/default/files/street-rally-s_0.jpg)

![Protestors march in support of the Catonsville Nine during the trial. The photo focuses on a young woman who leads the march. (William Morgenstern, [War and draft protest], 1968. Gelatin silver print. University Archives, University of Maryland, Baltimore County, UARC Photos-09-01-0030.)](/sites/default/files/styles/embed/public/protesters-female-lead-s.jpg?itok=mb19OvZZ)

![Protestors march in support of the Catonsville Nine during the trial. The photo focuses on a young woman who leads the march. (William Morgenstern, [War and draft protest], 1968. Gelatin silver print. University Archives, University of Maryland, Baltimore County, UARC Photos-09-01-0030.)](/sites/default/files/protesters-female-lead-s.jpg)

![Protests outside of the Baltimore courthouse, focusing in on a sign that says "Berrigan a black sheep in the priesthood." (William Morgenstern, [War and draft protest], 1968. Gelatin silver print. University Archives, University of Maryland, Baltimore County, UARC Photos-09-01-0034.)](/sites/default/files/styles/embed/public/berrigan-a-blacksheep-s.jpg?itok=LlzpCvmY)

![Protests outside of the Baltimore courthouse, focusing in on a sign that says "Berrigan a black sheep in the priesthood." (William Morgenstern, [War and draft protest], 1968. Gelatin silver print. University Archives, University of Maryland, Baltimore County, UARC Photos-09-01-0034.)](/sites/default/files/berrigan-a-blacksheep-s.jpg)

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)