Can you hear me now? The Birth of Wireless Communication on L Street

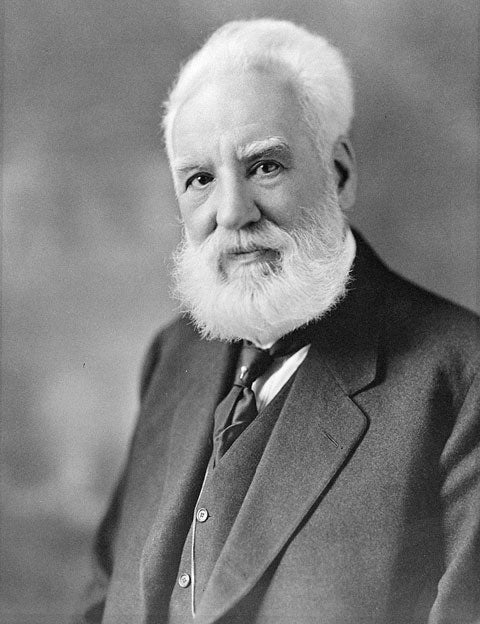

Of all the great minds to inhabit Washington, D.C. through the years, perhaps one of the most consequential yet often overlooked, was Alexander Graham Bell. Though his famous 1876 telephone experiment took place in Boston, Bell moved to the District shortly thereafter and worked on what he considered to be his greatest inventions in several Northwest labs over the next few decades. Of his many D.C.-based achievements, perhaps the most significant occurred at his small lab on L Street and led to the eventual birth of fiberoptic communication.

In 1877, Bell married Mabel Hubbard, a former pupil at his school for the deaf in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Mabel’s father, Gardiner Greene Hubbard, financed Bell’s early work on the “acoustic telegraph,” and served as the first president of the Bell Telephone Company (later AT&T). The Hubbards had recently relocated to Washington and the Bells followed suit shortly after returning from a year-long honeymoon in Europe.

Initially Bell was hesitant to leave Boston, writing to Mabel “I am afraid a quiet life in Washington is too good a thing to be hoped for.”[1] Mabel, however, missed being close to her parents and sisters, and was eventually successful in convincing Bell to make the permanent move in 1879, writing, “Alec has stopped railing at Washington and is beginning to find there are nice and scientific people here.”[2] Gardiner Hubbard purchased a house for the family at 1500 Rhode Island Avenue NW, commonly known today as the Brodhead-Bell-Morton Mansion.[3]

Once settled, Bell established his first D.C. laboratory at 1325 L Street NW “for developing new telephone transmitters and pursuing methods of recording sound and measuring distance by means of sound.”[4] His former assistant, Thomas Watson (of telephone fame), was serving as the Superintendent of Manufacturing at the Bell Telephone Company and was thereby unavailable. So on October 15, 1879, Bell hired Charles Sumner Tainter to be his lab assistant for $15 per week and they started work on Bell’s newest project: the photophone.[5]

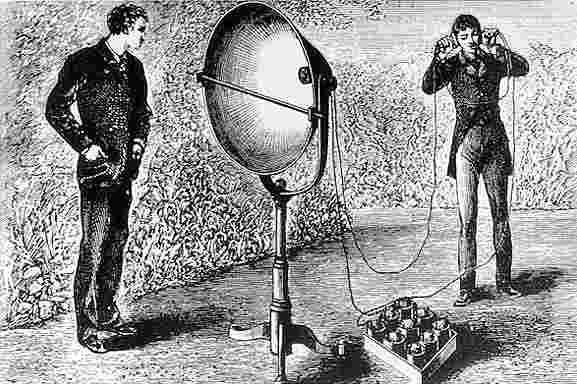

The photophone, created using a “sensitive selenium crystal and a mirror that would vibrate in response to a sound,” was ultimately “a device that enabled sound to be transmitted on a beam of light” and would “act in all things, like an ordinary but indestructible telephone.”[6] The first success of this project came on February 19, 1880 inside the L Street lab when they “interrupted, by means of a rotating perforated disk, a stream of sunlight falling upon a selenium cell. A musical tone was then heard from a telephone receiver connected in series with the selenium and a battery.”[7] To test this further, Tainter stayed with half the apparatus while Bell went to the lab basement with a pair of telephone receivers connected to the selenium cell. On the first trial, Bell clearly heard Tainter say “Hoy, hoy” and sing Auld Lang Syne through the device. They then switched places and replicated those results. Bell was thrilled and wrote to his father on February 26, 1880 saying: “I have heard articulate speech produced by sunlight! I have heard a ray of the sun laugh and cough and sing!”[8]

Over the next few months, Bell and Tainter worked on their invention secretly on L Street (high-level lawsuits over the telephone patent had Bell hesitant to make any premature announcements). On April 1, 1880, they used the apparatus to transmit their voices a distance of 79.62 meters down an alley on Massachusetts Avenue to a back window of their lab.[9] Of this success, Bell wrote: “We have thus at last succeeded in accomplishing the object for which we have been working and have produced the sounds of articulate speech at a distance by the action of light. It is now a question of perfection of apparatus in order to enable us to reproduce at places thousands of meters away the tones and articulation of a speaker’s voice by the action of an undulatory beam of light.”[10]

The Franklin School at 925 13th Street NW (present-day Planet Word Museum), was the site of Bell and Tainter’s crowning moment with the photophone. The school, just two blocks from their L Street lab, served a uniquely historic purpose in and of itself. Completed in 1869 and designed by the renowned D.C.-architect Adolf Cluss, the Franklin School “was the flagship building of a group of seven modern urban public school buildings constructed between 1862 and 1875 to house, for the first time, a comprehensive system of free universal public education in the capital of the Republic.”[11] The Reconstruction-era brought the revelation that access to public education was essential to the survival of a democratic society, and this school was both a prominent first-step in that direction and the first of its kind in D.C.— in fact, the children of Presidents James Garfield, Andrew Johnson, and Chester Arthur all attended the Franklin School.[12]

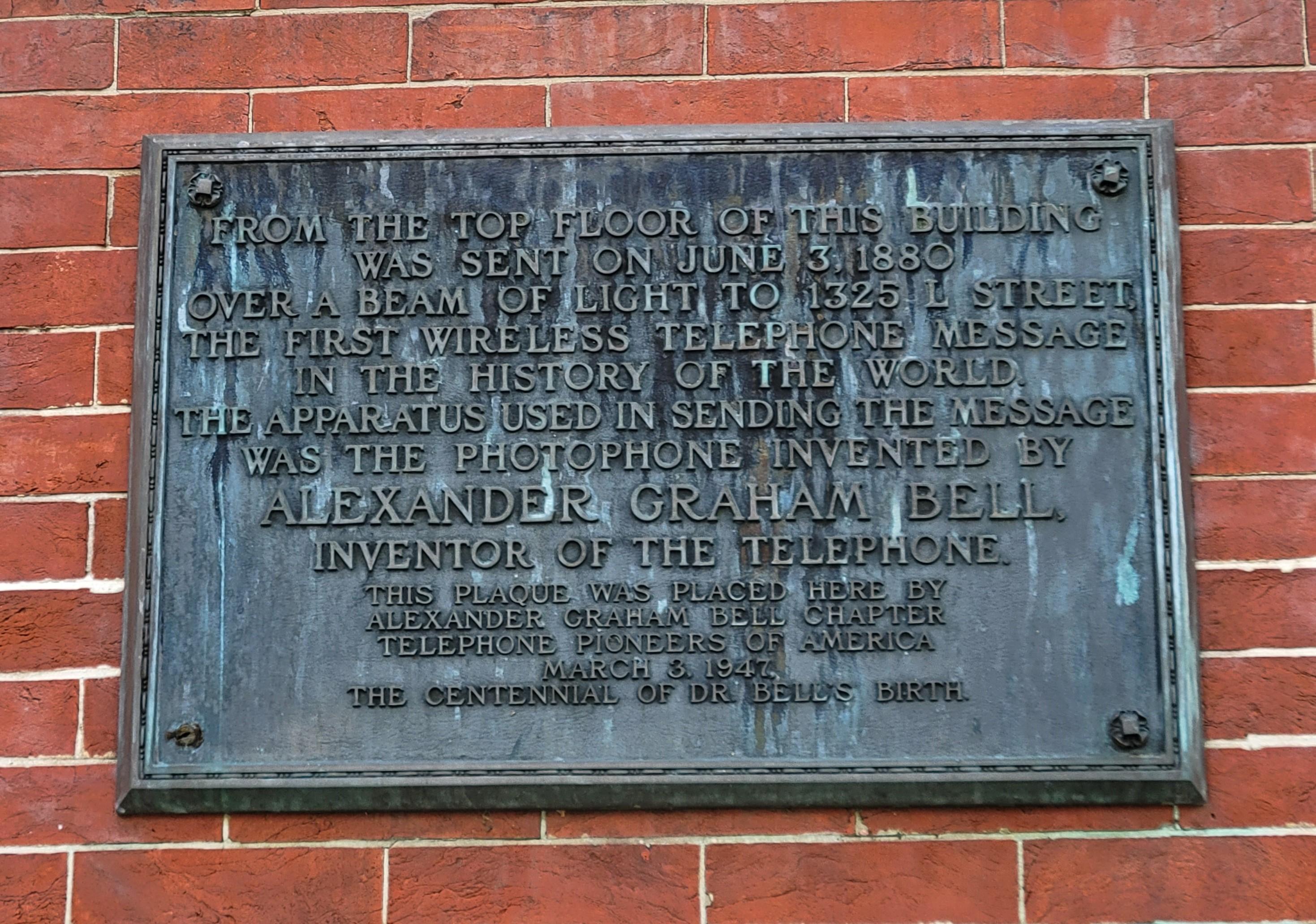

On June 3, 1880, the Franklin School added another historical achievement to its storied past. With a newly developed and perfected photophone apparatus in tote, Tainter went to the roof of the school and attempted to transmit sound 213 meters back to Bell through a window of their L Street lab.[13] It was a resounding success (pun intended), and the first ever instance of long-distance wireless communication— even preceding wireless radio voice communication by nearly 20 years.

In his lab notebook, Bell later wrote, “I distinctly heard the sentence ‘Mr. Bell— if you understand what I say come to the window and wave your hat.’”[14] Years later speaking at Cornell University, he reflected: “It is unnecessary to say that I waved with vigor, with enthusiasm which comes to a man not often in a lifetime…[and such moments] are worth a lifetime to live for.”[15]

On February 19, 1980, exactly 100 years to the day of Bell’s first success with photophone technology, representatives from National Geographic, the Smithsonian, and Bell Laboratories gathered on the street outside the former site of Bell’s L Street lab and paid tribute to Bell with a photophone demonstration on the Massachusetts Ave alley.[16] This celebration was coupled with an exhibit celebrating the photophone at the National Geographic Society’s D.C. headquarters— a society founded and led for many years by close members of Bell’s family. The Smithsonian even lent Bell’s original photophone to National Geographic for the centennial exhibit.

Aside from the photophone, Bell achieved numerous other successes in Washington, mostly at his 1221 Connecticut Avenue lab, aka Volta Laboratory.[17] One of these was a metal detector he invented to locate the bullet which ultimately killed President Garfield in 1881; Bell was not able to accurately find the bullet in Garfield’s body due to interference from metal coils inside the President’s new mattress— the device did however successfully locate bullets lodged in Civil War veterans.[18] Other Washington-born inventions were the gramophone, a novel device that could record and playback sound, as well as the cylinder record, another sound recording medium.[19]

In addition to these groundbreaking inventions, Bell also founded The Volta Bureau in 1887, “an organization for the increase and diffusion of knowledge relating to the deaf.”[20] By 1893, the Bureau had outgrown his father’s small carriage house, and ground was broken on the “neoclassical yellow brick and sandstone building” at 3417 Volta Place NW, just opposite Georgetown University.[21] It was a young Helen Keller who had the honor of turning the first piece of sod at the groundbreaking ceremony on May 8, 1893— she and Bell communicated regularly for many years and in 1903, Keller dedicated her autobiography to him.[22] Bell considered his work in deaf education some of his most meaningful, holding deep familial connections to the deaf community between his wife and mother.

Of all these successes, though, it was the photophone which Bell called “the greatest invention I have ever made; greater than the telephone.”[23] As he predicted, the implications of his Franklin School experiment had long lasting effects on technology— in fact, the photophone “reveals the principle upon which today’s laser and fiber optic communication systems are founded, though it would take the development of several modern technologies to realize it fully.”[24] So, it is thanks to Alexander Graham Bell (and maybe a little nudging from his wife), that nearly all forms of modern communication can be traced back to a few quiet labs in Washington, D.C. And how very lucky we are for that!

Footnotes

- ^ Charlotte Gray, Reluctant Genius: Alexander Graham Bell and the Passion for Invention (Arcade Publishing, 2006), 205.

- ^ Gray, 205.

- ^ “Brodhead-Bell-Morton Residence,” DC Historic Sites, accessed April 11, 2022, https://historicsites.dcpreservation.org/items/show/866.

- ^ Forrest M. Mims III, “The First Century of Lightwave Communications: A History Beginning with Alexander Graham Bell’s ‘Photophone’ in 1880 and Emphasizing Early Atmospheric Transmissions,” Fiber Optics Weekly Update 1 (1982 1981): 6–14. 7.

- ^ Mims III, 7.

- ^ “Another Great Invention.,” The Washington Post (1877-1922), September 26, 1880, https://www.proquest.com/hnpwashingtonpost/docview/137793938/abstract/2… ; “Inventor and Scientist | Articles and Essays | Alexander Graham Bell Family Papers at the Library of Congress | Digital Collections | Library of Congress,” web page, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA, accessed June 15, 2022, https://www.loc.gov/collections/alexander-graham-bell-papers/articles-a….

- ^ Mims III, 10.

- ^ Mims III, 10.

- ^ Mims III, 11.

- ^ Mims III, 11.

- ^ “National Historic Landmark Nomination - Franklin School,” accessed June 15, 2022, https://npgallery.nps.gov/NRHP/GetAsset/80f16cc7-2289-41da-91f7-27c5e85….

- ^ “National Historic Landmark Nomination - Franklin School.”

- ^ Andy Mabbett, Commemorative Plaque on Franklin School, Washington DC., July 15, 2012, Own work, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Franklin_School_-_Alexander_Gra….

- ^ Robert V. Bruce, Bell: Alexander Graham Bell and the Conquest of Solitude (Boston, MA: Little, Brown, 1973), 338.

- ^ Bruce, 338.

- ^ Mims III, 6.

- ^ Carlene E. Stephens, “Part 2: Alexander Graham Bell’s Capital Addresses,” National Museum of American History, July 1, 2015, https://americanhistory.si.edu/blog/part-2-alexander-graham-bells-capit….

- ^ Stephens.

- ^ Stephens.

- ^ J. Barton Miller, “THE TEMPLE OF SOUND: That Is What the Volta Bureau Will Be to the Deaf.,” The Washington Post (1877-1922), June 24, 1894, sec. General, https://www.proquest.com/hnpwashingtonpost/docview/139164235/abstract/6….

- ^ “Volta Bureau (U.S. National Park Service),” accessed April 11, 2022, https://www.nps.gov/places/volta-bureau.htm.

- ^ “WITH UNIQUE CEREMONY.: A Blind and Deaf Girl Breaks Ground for the Volta Bureau Building.,” The Washington Post (1877-1922), May 9, 1893, https://www.proquest.com/hnpwashingtonpost/docview/139010782/abstract/4…. ; Helen Keller, The Story of My Life (Doubleday, Page & Company, 1903).

- ^ “Inventor and Scientist | Articles and Essays | Alexander Graham Bell Family Papers at the Library of Congress | Digital Collections | Library of Congress.”

- ^ Ibid.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)