The First Electric Census, Brought to You by the Hollerith Tabulator

In 1888, the Census Bureau was facing a problem of literally continental proportions. It had only just closed the books on the 1880 census, giving them barely two years before the new one was scheduled to begin. The Bureau seemed to be approaching the limit of what it could process by hand, and the 1890 census promised to be even more labor-intensive than its predecessor. America’s population was on the upswing, and soon millions of responses on age, race, occupation, literacy, and education would descend upon the Bureau (not yet its own institution but smushed awkwardly into the Department of the Interior). How would the census clerks tackle the coming decade when the 1880 count had “overwhelmed [them] with material”?1

The problem lay in the time-consuming and error-filled process of recording and processing millions of census forms individually by hand. If the data process could be simplified or mechanized, they could condense the whole timeline. The Census Bureau put out a call to the American people in 1889: any machine that could record and tabulate population data was welcome. Whoever could tabulate sample data the fastest would be awarded a contract to furnish the count for 1890.

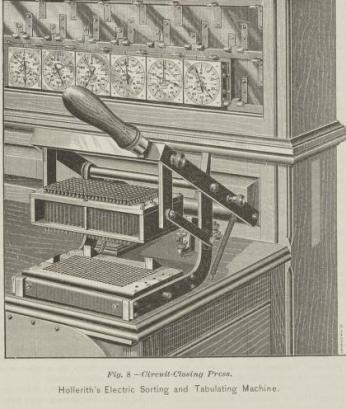

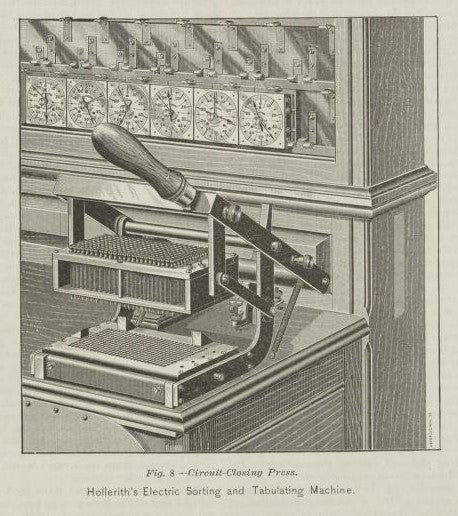

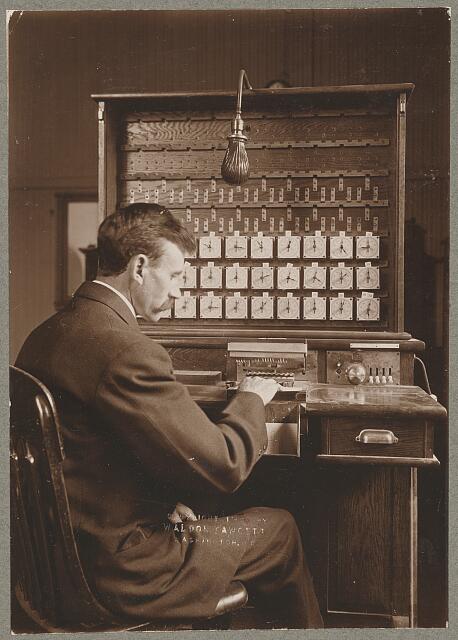

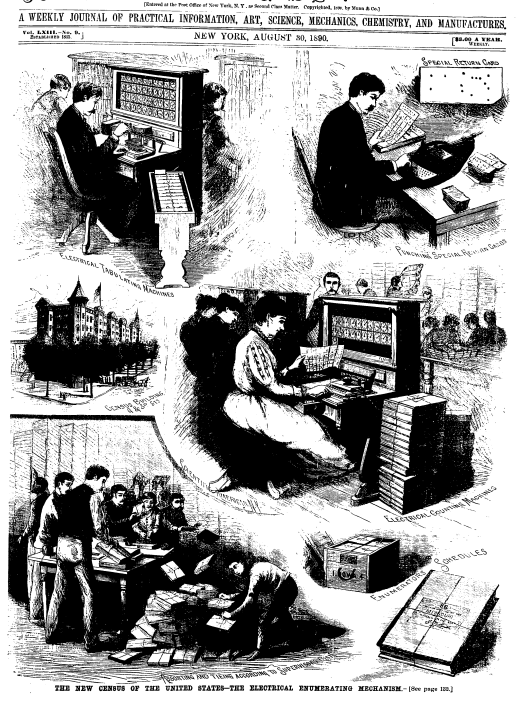

One of the men to respond was Herman Hollerith, the New York-born son of German immigrants and a teacher of mechanical engineering at MIT. He approached the Bureau with a machine about the size of an upright piano inside of a “handsome oak case."2 Its face was covered with dials and on its front was a box that looked like a sandwich press full of needles. As odd as it looked, the machine blew its competition out of the water. Each applicant had to capture and prepare sample data from St. Louis: Hollerith’s machine captured data in 72 hours compared to 100 and 144 hours from its competitors. It could prepare data even faster: the other machines took 55 and 44 hours, while Hollerith’s tabulator was finished in just five.3

The Bureau superintendent must have breathed a sigh of relief handing Hollerith the contract! As the clerks prepared to operate their new machines, the Bureau happily predicted each operator could capture around 500 census forms every day.

Hollerith was actually not a new face in the Bureau. He had worked as a statistician in the Population Division during the 1880 count and saw firsthand how slow and inefficient it was to have clerks record data by hand. He met the director of the Vital Statistics Division, John Shaw Billings, who told Hollerith there must be ““some mechanical way of doing this job” if only someone developed “a machine for doing the purely mechanical work of… population and similar statistics.”4 He encouraged Hollerith to tinker with the problem, and he applied for his first patent in 1884 to store data in hole-punched paper strips (much like a player piano).5

Realizing that rolls were impractical for such large amounts of data, Hollerith switched to cards in the patent for his tabulator, filed in 1887. According to Hollerith’s daughter, he came up with the idea of cards on a trip West. On a train, he was handed a “punch photograph”: a space on a ticket where a conductor punched out data points describing the traveler like “light hair, dark eyes, large nose, etc.” The machine with which he won the contract for the 1890 census ran on the same principle, taking “punch portraits” of each American.6

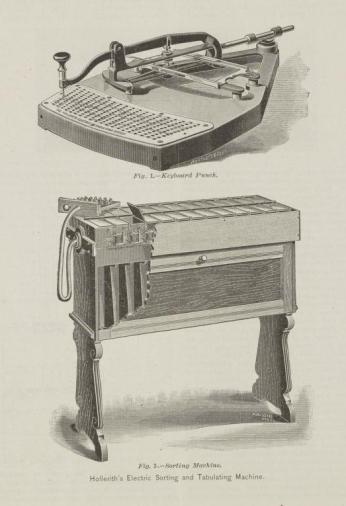

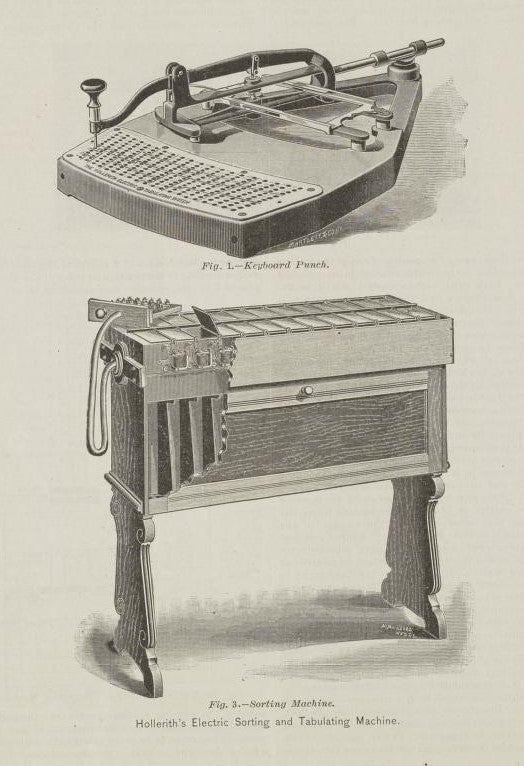

The Hollerith Tabulator consisted of four main parts and could be operated by two clerks. The first clerk punched the data cards using a pantograph. This machine had a template with holes that corresponded to data points (for example, a punched fourth hole might mean the respondent is married). When the stylus over the template was lowered, a corresponding punch was made in the tabulator card, “storing” that data there. A clerk could prepare 500 of these cards a day, though that average went up over time.

Next the cards would pass to the clerk operating the freestanding machine. Clerks opened the card reader (the bit that looked like a metal sandwich press) and slotted one punch card in at a time. When they closed it, an array of pins would fall, passing through any holes in the card into a tray of mercury beneath and completing a circuit. This current would send a tiny electric current to the dials above.

Each of the forty dials represented a different data point and would tick forward only when its corresponding pin fell through a hole-punch into the mercury. Since these punches were basically on-off switches, Hollerith’s machine employed the first computing form of binary. The dials could even be programmed to process “and” statements (for example, a card belonging to a person who was baker and from Tennessee), a level of sophistication unheard of in the 1890s.7 When the machine had processed a set of cards, the clerk would record the values of each dial, reset them, and begin again.

Later, Hollerith added an electric sorting table which was attached to the tabulator by a cable. Each of the 24 drawers could be programmed to collect a different data point. When the clerk removed a card from the tabulator, a drawer would automatically open on the table for the corresponding data tag. An experienced clerk could process 80 cards through the tabulator and sorting table in a single minute!8

The Census Bureau paid Hollerith $3 a day for the use of each machine. If a machine was not up and running, it didn’t earn its pay.9 Their rollout wasn’t completely smooth sailing, either: the original paper cards fell apart and clogged the mercury trays. The clerks also would mistakenly flip the blank cards upside down or backwards, skewing the data. The Bureau began cutting the top left corners of cards to keep them in the right orientation for tabulation.10

Each card, once it had been processed twice to made sure the clerks’ counts were accurate,11 went into one of 25,000 tin cans, each twenty by seven inches, that would store the 1890 records (though they perished almost completely in a 1921 fire).12 Overall the machines processed more than sixty million cards, each one fed manually into the readers—but still much faster than counting by hand!

The 1890 Census discovered 25.5% increase in the US population, tallying almost 63 million people. The count collected so much data that stacking each schedule on top of each other would have made “a pile of sheets taller than the Washington Monument.”13 Each of the female clerks averaged 9,590 families and 47,000 individuals each.14 The 1890 census also officially closed the American frontier; the Bureau announced the West was populated enough to make the concept irrelevant.

How much time Hollerith’s tabulators saved the Bureau is debated. Sources propose anywhere from a month and a half to three years, but the general count was nearing completion by August of 1891. By December 1891, the Bureau had published ten times as much information as it had at the same time a decade ago.15 The cost of processing the census went down by $5 million.16 The Hollerith tabulating machine had been a roaring triumph for the 1890 Census.

After well-deserved success in the United States, Hollerith made a tour de force with his machine. He was awarded the Elliott Cresson medal by the Franklin Institute and won medals at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair and 1889 Paris Exposition. Countries as distant as Austria and the Philippines requested Hollerith tabulators for their own counts. Russia’s very first census was completed on Hollerith machines.17 Orders rolled in from private businesses and state agencies who used them for data processing, accounting, and sales analysis.

Hollerith tabulators were used for the Census in evolving forms until the 1950s, when computers replaced them. Hollerith retained his leasing rights for his original tabulators until 1910, after his main patents expired and the Bureau, seeking to cut costs, set about developing in-house machines.

But the Hollerith tabulator has perhaps a more interesting legacy. After his census contract had boosted him to fame, Hollerith founded his own company in 1896 to market and produce his machines. In 1911, he sold it to financier Charles Flint for $2.3 million ($74 million in 2024). At the new Computer Tabulating Recording Company, Hollerith stayed on as a consulting engineer, tinkering with improvements like a verificator machine: “by… hitching up a lot of relays you get a machine which will handle cards at the rate of four hundred per minute and… throw out all inconsistent cards, such as widows [who are] five years old.”18

In 1924, the CTR Company was renamed the International Business Machines Corporation—or IBM, now better known for its hyperintelligent computers that dominate on Jeopardy! and help doctors treat cancer patients. You heard it here first: Watson’s great-grandfather was once a humble, clunky machine on the floor of an 1890 Census Bureau office whose sole task was to dutifully punch away a portrait of every man, woman, and child in America.

Footnotes

- 1

Connecticut western news. [volume] (Salisbury, Litchfield Co., Conn.), 29 Feb. 1888. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- 2

The Sully County watchman. (Clifton, Dakota [S.D.]), 06 Sept. 1890. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- 3

US Census Bureau. “The Hollerith Machine - History.” U.S. Census Bureau. Accessed February 20, 2024.

- 4

Emmanuel, Lauren. “Count Me In.” US Patent Office. Accessed February 20, 2024.

- 5

IBM. “The Punched Card Tabulator.” Accessed February 20, 2024.

- 6

Hollerith, Virginia, and Herman Hollerith. “Biographical Sketch of Herman Hollerith.” Isis 62, no. 1 (1971): 69–78.

- 7 Parker, Matt (Stand-Up Maths). “The 1890 US Census and the History of Punchcard Computing [Feat. Grant of 3blue1brown Fame].” Video. YouTube, April 28, 2020.

- 8

US Census Bureau. “The Hollerith Machine - History.” U.S. Census Bureau. Accessed February 20, 2024.

- 9

The Salt Lake herald. [volume] (Salt Lake City [Utah]), 19 April 1891. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- 10

Hollerith, Virginia, and Herman Hollerith. “Biographical Sketch of Herman Hollerith.” Isis 62, no. 1 (1971): 69–78.

- 11

The Salt Lake herald. [volume] (Salt Lake City [Utah]), 19 April 1891. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- 12

The Sully County watchman. (Clifton, Dakota [S.D.]), 06 Sept. 1890. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- 13

The Salt Lake herald. [volume] (Salt Lake City [Utah]), 19 April 1891. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- 14

Fort Worth weekly gazette. [volume] (Fort Worth, Tex.), 28 Aug. 1890. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- 15

Cruz, Frank da. “Herman Hollerith.” Columbia University, November 2001.

- 16

IBM. “The Punched Card Tabulator.” Accessed February 20, 2024.

- 17

“Electric Tabulation Machine.” The Franklin Institute, March 8, 2014.

- 18

Hollerith, Virginia, and Herman Hollerith. “Biographical Sketch of Herman Hollerith.” Isis 62, no. 1 (1971): 69–78.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)