The Cost of Urban Renewal in Southwest DC

At the end of World War II, Washington, DC was the shining city on a hill. In contrast to the endless bombings and shellings experienced by other Allied capitals— London, Paris, and Moscow— Washington was physically unharmed; its buildings, monuments, and sites which makes up America’s illustrious past and bright future as a global power were no worse for wear.

According to popular lore among longtime residents of the Southwest quadrant of DC, though, one rival world leader was delighted to see the District saved from the perils of the world’s most deadly and destructive conflict: Nikita Khrushchev, the leader of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964.[1] As Europe struggled to pick up the pieces of the Second World War, the United States was in the midst of an economic boom but, as Khrushchev was quick to point out, not all Americans shared in that prosperity – just look at the American capital city.

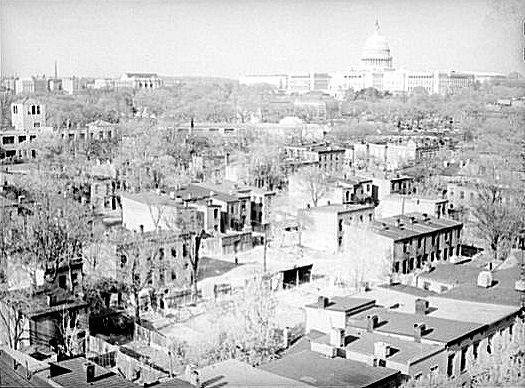

As the story goes, the Soviet leader got his hands on images of Washington that pictured the blighted neighborhood of Southwest DC.[2] Overcrowded, poor, and largely African American, the ramshackle homes in the foreground poignantly clashed with the looming view of the Capitol building— just a mere eight blocks away— in the background.[3] To Khrushchev, this highlighted the massive disparity which existed between America’s most vulnerable population and the wealth and comfort experienced by those who ran the government. To make his point, he supposedly went around to various European leaders and used the photographs as propaganda – a warning of the supposed dangers of capitalism.

While such a move should not be a surprise given the fact that the United States and the Soviet Union were in the midst of the Cold War in which they vied for global influence, the optics of the situation were not ideal for the United States. Large-scale poverty in view of the capital of the free world was a ready-made talking point for the Soviets. In essence: the U.S. clearly could not take care of their own people so why should rebuilding and developing nations follow in its footsteps on a path to democracy and free market capitalism?

Supposedly, when the U.S. government got wind of Khrushchev’s propaganda campaign, there was an urgent response to rewrite the narrative. The federal government promptly seized the most land it had ever taken (up to this point) through eminent domain.[4] It proceeded to raze almost all of Southwest, and build it up to something more fitting for a world capital. Ultimately, this project would be the most comprehensive bout of urban renewal in D.C. history.[5]

In reality, the story detailed above is probably more lore than fact. It’s unlikely that Krushchev spurred the redevelopment of Southwest Washington – the wheels had been turning years before he came to power in Moscow. However, while the actual story may lack the intrigue of Cold War politics, the actions taken by the United States government are an all too real part of the city’s history – and that history is marked by the removal, displacement, and false promises made to the predominantly African American residents who once made up this historic neighborhood.[6]

Going back decades, Southwest Washington had been the home of a large, if also largely poor, African American population. Following the population boom of the War years, the area was immensely overcrowded.[7] Homes intended for single families were partitioned into multiple-family units and residences were built in every nook and cranny available.[8] More often than not, these buildings were constructed in the alleys between other homes.[9] These alley dwellings (as they were known) frequently lacked ventilation, making them incredibly unsafe to inhabit.[10] A vast majority of the buildings were shoddily built of wood, meaning they were prone to fires and many were falling apart by the early 1950s.[11]

On top of being an overly populated area, Southwest fell short in providing its residents with basic accommodations we take for granted. Indoor plumbing was a luxury in this part of town.[12] For example, a staggering 43% of people in Southwest still used outdoor toilets.[13] A whopping 24% had no electricity, and another 70% lacked central heating.[14] The problem was that few residents could not afford anything beyond these meager offerings. Landlords knew this and neglected their properties, realizing that they would make a profit even by ignoring essential maintenance and upkeep.[15]

Despite the substandard living conditions, the community was tightly knit and filled with history. In the nineteenth century, Southwest was a haven for formerly enslaved individuals. With such a demographic and its proximity to states where chattel slavery was legal, it is no surprise that the neighborhood was a majorly important stop along the Underground Railroad.[16] Unlike other poorer sections of contemporaneous American cities, Southwest’s residents— for the most part— lived in the area for long periods. Statistics from the point right before urban renewal found that 65% of the citizenry lived in Southwest for over ten years, while less than 1% had recently moved over the course of the previous year.[17]

Furthermore, although the neighborhood’s racial makeup was primarily African American in the years leading up to urban renewal (80% of a population of 23,500), other marginalized groups of the day— like Irish and Jewish people— found homes, livelihoods, and communities in this part of the city.[18] Those who resided in Southwest may not have had much money, but they were close to one another. In the mid-20th century those bonds – to each other and their neighborhood – would be tested.

In post-World War II America, a phenomenon known as “urban renewal” swept the nation, marketed as a way to upgrade substandard and outdated housing and public works with large scale redevelopment.[19] In 1945, Congress passed the Redevelopment Act, which authorized the creation of the Redevelopment Land Agency (RLA).[20] (The District did not have Home Rule during this period, so all decisions pertaining to the city were made by Congress.)[21] Congress enabled the RLA the use eminent domain to seize all property it found unsuitable for sanitation or beautification reasons.[22] Though the act was challenged in court, it was upheld by the Supreme Court in the 1954 case Berman v. Parker. With its power now codified, the RLA set its sights on its first major project: the revitalization of Southwest Washington.

The RLA’s plan for Southwest was sweeping in scope and, ultimately, execution. The proposal called for the overhaul of 552 acres (basically the entirety of the quadrant.)[23] The project was broken up into three sections (called B, C, and C1) and set into motion in 1954. Acquisition of homes, buildings, and businesses by the RLA commenced.[24] When everything was said and done, the RLA had 99% of Southwest under its control.[25] Of the property bought through eminent domain, nearly all was torn down.[26] Only a select handful of culturally significant structures, such as St. Dominic’s Catholic Church and the Fifth Baptist Church, were saved from the wrecking ball.[27] Even the Municipal Fish Market on Maine Avenue (whose claim to fame as the oldest continuously operating fish market in the nation) was under threat of removal without the option for replacement.[28] It took the owners of the stalls at the Fish Market to fight tooth and nail to have Congress grant their businesses a particular priority, instituted by an Act of Congress for the historic building to be spared from the demolition crews.[29]

As their neighborhood was being transformed before their eyes, Southwest residents tried to figure out how they fit into the new, modernized Southwest – and had mixed feelings. As Ezekiah Cunningham, a displaced eighty-four-year-old African American corner grocery store owner, told The Evening Star, in 1954 “Well, it seems like they’re handin’ out a passel o’ joy and a passel o’ sorrow.”[30]

By law, the RLA had to aid in finding each family a new place to live and the government promised an affordable home for any resident who was evicted.[31] Due to accompanying programs that helped furnish new apartments, provided medical services, and gave $200 to aid in moving costs, there were measures in place to ease the transition for displaced residents. In 1954, Friendship Baptist Church pastor Rev. Benjamin H. Whiting, who ministered to many who faced removal in Southwest, characterized the attitude as follows:

On the whole, they are satisfied. They don’t want to leave the Southwest because they love it. But they know this is a good thing and that they will be getting better homes. Many of them also feel it is just temporary—they want to come back when it is rebuilt. They know rents will be higher. But they also know a lot of people have been paying $10 a week for just one room in the way it is now.[32]

Unfortunately, however, most of those who held out hope of returning would end up disappointed. While some subsidized housing options were made available for those in less affluent circumstances, the supply was not nearly enough for the number of individuals who needed the assistance.[33] The government allowed some developers to renege on their promises when it came to affordable units. For example, at the outset of the project, the developers for project area B had said a third of their proposed housing would be subsidized for low income families.[34] However, when construction was complete, the developers claimed that the number of low-income units was too expensive and received permission to charge market price instead.

So, by the 1970s when the final hammer was put down in the name of Southwest DC urban renewal, what was the result? A community makeup that looked very little like the original neighborhood. For every three families forced to leave due to the project, only one would return to live in the shiny new mid-century modern Southwest.[35] 1,500 businesses and 23,000 mostly black residents were removed.[36] Some 43% of the former residents moved to Southeast, 21% to Northeast, 15% to Northwest, and 6% moved out of the city all together.[37] At the end of the day, only 13% of the original Southwest population returned to the neighborhood.[38] The majority of those who came to live in the new Southwest were white and middle-class.[39]

The neighborhood was not only emotionally separated from its original look and feel, but it was also separated physically from the rest of the city with the creation of I-395.[40] Just another part of the RLA’s urban renewal plan, the elevated nine-lane highway made Southwest feel as if it was removed from the rest of DC because in many ways, it was.[41] Major roads like Maryland Avenue were cut off from going out of the neighborhood.[42] This made it more difficult for traffic and people to come into Southwest and effectively kept residents within the confines of the quadrant.[43]

In many respects, it seems sweeping away the lower class was one of the main objectives of the plan all along.[44] In the aftermath of World War II, middle-class families moved into the suburbs due to the economic solvency many men received through the GI Bill.[45] Then with the Interstate Highway Act of 1956, it became increasingly easier to work in the city but live miles outside. This mass exodus – often referred to as the white flight – accelerated in the 1960s and resulted in a substantial decrease in tax revenues for American cities.[46] The hope for Southwest was that it would encourage middle-class whites to come back to the city, bolstering the overall income of the District.[47] The creation of places like the tenth street indoor shopping mall, and complexes for corporations to thrive encouraged middle class populations – who were largely white – to move into Southwest.[48] In the process, most less affluent African American residents would be priced out. Historians refer to this practice as economic segregation.[49] This economic segregation had lasting impacts in Southwest. Not until recent years has the African American population in the neighborhood come close to the pre-urban renewal numbers (about 50% of the residents are black today.)[50]

Urban renewal and its carryover — gentrification— may make an area more economically prosperous and sanitary, but at what cost? Communities, unIike other fixtures, are incredibly hard to replace. Statistics found that the social health of former Southwest residents declined, with nearly a quarter of the population not making a single friend in their new neighborhood by 1966.[51] In addition, the project achieved very little of what it set out to accomplish other than clean up the blighted area.[52] While urban renewal provided sleek new living accommodations for those who could afford them, other key parts of community building – such as enticing restaurants, cultural institutions like theaters and museums, and destination shopping – never really took hold on a large scale.[53] Unless people lived in Southwest, there were few reasons to visit. As a result, the economic renaissance envisioned for the quadrant languished.

Perhaps the biggest testament to the failure of 20th century urban renewal in Southwest is that the area is currently in the midst of a second round of massive redevelopment just a few decades after the first project was complete. Today entertainment and dining options at The Wharf draw local and regional visitors to Southwest.[54] The area is touted as a destination and an economic driver for the city. Time will tell whether these promises are realized in the long term – and whether the benefits are felt by all rungs of the economic ladder. As old Southwest residents can attest, “progress” almost always comes at a cost and, in their neighborhood, a culturally and historically rich community was forever lost. That – unfortunately – is a big part of the legacy of Southwest.

Footnotes

- ^ “Brian Hamilton Interview,” interviewed by Jesse Card, Buzzard Point Oral History Project, Dig DC, September 6, 2017, https://digdc.dclibrary.org/islandora/object/dcplislandora%3A100996.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Flora Lindsay-Herrera, “One City for All? The Characteristics of Residential Displacement in Southwest Washington, DC,” Land 8, no. 2 (2019).

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “Brian Hamilton Interview.”

- ^ Robert J. Lewis, “Washington’s ‘Casbah’ Today” The Evening Star (Washington, DC) July 25, 1959.

- ^ “Vanessa Ruffin-Colbert Interview,” interviewed by Jesse Card, Buzzard Point Oral History Project, Dig DC, August 22, 2017, https://digdc.dclibrary.org/islandora/object/dcplislandora%3A101160.

- ^ “District Land Agency to Syndicate Plans for Harbor Area.”

- ^ Carolyn Swope, “The Problematic Role of Public Health in Washington, DC’s Urban Renewal.” Public Health Reports 133, no. 6 (2018).

- ^ “Brian Hamilton Interview.”

- ^ Lindsay-Herrera, “One City for All? The Characteristics of Residential Displacement in Southwest Washington, DC.”

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Historic American Buildings Survey, “Southwest Washington, Urban Renewal Area, Bounded by Independence Avenue, Washington Avenue, South Capitol Street, Canal Street, P Street, Maine Avenue & Washington Channel, Fourteenth Street, D Street, & Twelfth Street, Washington, District of Columbia, DC,” loc,gov, The Library of Congress, accessed June 30, 2022, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/dc1017/.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Lindsay-Herrera, “One City for All? The Characteristics of Residential Displacement in Southwest Washington, DC.”

- ^ George Beveridge, "Southwest Area Takes on Ghost Town Look," The Evening Star (Washington,DC), November 21, 1954.

- ^ HABS, “Southwest Washington, Urban Renewal Area. . .”

- ^ “Berman v. Parker.” Oyez. Accessed July 1, 2022. https://www.oyez.org/cases/1940-1955/348us26.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “Waterfront: A City Asset that Protects Business,” The Evening Star (Washington, DC), March 3, 1963.

- ^ “District Land Agency to Syndicate Plans for Harbor Area.”

- ^ Swope, “The Problematic Role of Public Health in Washington, DC’s, Urban Renewal.”

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “Picture Progress Report on Southwest Washington,” The Evening Star (Washington, DC), March 15, 1959.

- ^ “Waterfront: A City Asset that Protects Business.”

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Beveridge, "Southwest Area Takes on Ghost Town Look.”

- ^ “Brian Hamilton Interview.”

- ^ Beveridge, “Southwest Area Takes on Ghost Town Look.”

- ^ “Picture Progress Report on Southwest Washington.”

- ^ Russello Ammon, “Commemoration Amid Criticism: The Mixed Legacy of Urban Renewal in Southwest Washington, D.C..”

- ^ “Brian Hamilton Interview.”

- ^ HABS, “Southwest Washington, Urban Renewal Area. . .”

- ^ Russello Ammon, “Commemoration Amid Criticism: The Mixed Legacy of Urban Renewal in Southwest Washington, D.C..”

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ The Evening Star (Washington, DC), September 23, 1962.

- ^ Craig Cook and John K. Burke, “How the Highway Killed Washington’s Waterfront and How the City Plans to Bring It Back to Life,” Bloomberg.com, Bloomberg, May 8, 2013, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2013-05-08/how-the-highway-killed-washington-s-waterfront.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ HABS, “Southwest Washington, Urban Renewal Area. . .”

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Joseph Byrnes “Firm Plans Aviation, Space Communications,” The Evening Star (Washington, DC), March 10, 1962.

- ^ Lindsay-Herrera, “One City for All? The Characteristics of Residential Displacement in Southwest Washington, DC.”

- ^ Russello Ammon, “Commemoration Amid Criticism: The Mixed Legacy of Urban Renewal in Southwest Washington, D.C..”

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Quinlyn R Spellmeyer, “Southwest DC: A Cycle of Urban Renewal and ‘Revitalization,’” storymaps.arcgis.com, Demeter 16, 2020, https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/f43a96703b3e4d098b7c242d680e3498.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)