How the B&O Railroad Almost Gave Kensington, Maryland its Name

Montgomery County commuters: on your way into Washington, D.C. every morning, have you ever really looked at the stations around you? As the MARC commuter train pulls into Kensington, for example, passengers board and disembark at a historic station that opened in 1891—and has been running ever since! It’s the second-oldest continuously operational railroad station in the country, actually.[1] It’s also the station that gave the area its history and name, albeit a different name than the one we see today.

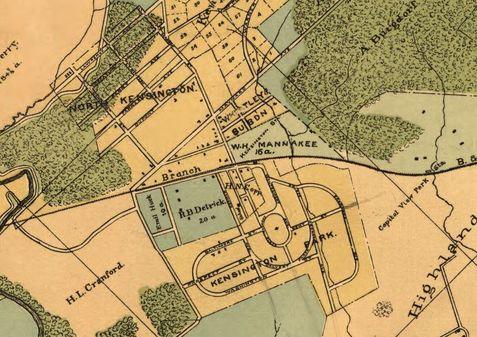

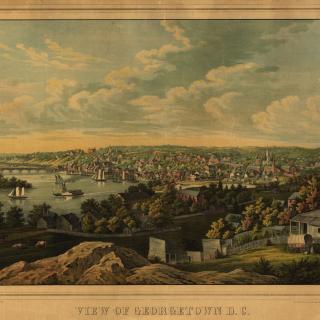

In 1873, the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad opened a new branch that connected Washington, D.C. to towns in western Maryland, like Frederick and Hagerstown. The Metropolitan Branch ran from downtown D.C. through Montgomery County—which, at the time, was almost completely rural. In addition to a few “summer cottages” owned by rich Washingtonians, there were farms, general stores, and a couple of service stations along the local highways.[2] Safe to say that, when the railroad tracks came through the area, the farmland became a lot more valuable. The capital district was expanding.

Though there weren’t many people living there yet, a station was erected in the area in 1891. It served the cluster of shops, houses, and other buildings that had sprung up along the old Bethesda-Bladensburg Road and Rockville Pike throughout the nineteenth century.[3] Needing a name for this station in the middle of nowhere, the railroad company gave a nod to the Knowles family, whose farmland surrounded the station and tracks. Thus, “Knowles Station” was born.

Shortly after the introduction of the railroad, Knowles Station started to boom into a proper little town. The 1890s saw the beginning of suburban development in the D.C. area. The prevalent belief that the “countryside” was healthier and cooler in the summertime attracted wealthy and middle-class Washingtonians to the outskirts of town, where they established summer residences that were still within reasonable distance of their jobs. The local railroad station meant that Knowles Station was now open for this kind of development. Upon the deaths of the Knowles landowners, their 220-acre farm was divided into several lots and sold off to developers, all of whom saw the potential in this little hamlet and scrambled to get a piece of valuable land.[4]

One of these developers was Brainard Warner, who operated a successful real estate, construction, and financing company in D.C. In 1892, he purchased a large parcel of farmland just south of Knowles Station and built an impressive summer mansion for his family.[5] The Warner Manor—which still stands in historic Kensington—was built to reflect Warner’s idealistic view of life outside the city. The traditional English architecture, planned gardens, and rolling green spaces communicated Warner’s vision of an oasis mere miles from the hot and crowded national capital. He was convinced that, if he enjoyed his property that much, other people would, too.

Warner conceived the idea of a planned “garden suburb” after a trip to London, where the genteel suburbs surrounding Kensington Palace and its gardens offered wealthy and middle-class residents a quiet city life. One-by-one, Warner sold parcels of his land to friends and other clients, mapping out his ideal community.[6] When we think of suburbs today, we tend to think of hundreds of curated homes that lack character—think the Levitt suburbs of the 1950s and 1960s. Warner had a similar vision, but his plans allowed for development that seemed organic. The new mansions continued the theme of English Victorian architecture and allowed for lots of green space. The winding, curved roads throughout were designed to contrast the strict grid layout of downtown D.C. Warner also planned for community buildings—a Presbyterian Church, space for The Montgomery Press local newspaper, and the public library.[7] Warner called his development “Kensington Park,” after his English inspiration.

Though many of the residences at Knowles Station began as summer homes, the improvement of transportation throughout the 1890s allowed for year-round residents to settle in these planned communities. The population of this once-small settlement boomed, thanks to the attractive homes built by Warner and other developers. In 1894, Knowles Station was set to be officially incorporated as a town in Maryland. Warner, though, wasn’t too thrilled that the local post office and railroad station still used the old name instead of the one he chose for his community. Determined that the issue would be rectified upon incorporation, Warner petitioned for the official name change to Kensington. Using his influence, locally and in the government, he got his way.[8]

Kensington Park, the original suburb of Warner’s creation, still exists in modern-day Kensington. Listed on the National Register of Historic Places, the entire area around the original Warner Manor exists today as a community park and historic site. Residents and visitors can also see Warner’s church, the Noyes Library, and other examples of late-nineteenth-century mansions and gardens.[9] Though the town has expanded, this example of a traditional, idealistic garden suburb survives.

And, of course, the original Knowles Station continues to serve thousands of commuters every day, even if it’s under a different name. The town knows that it owes its creation to the station—in fact, according to the Kensington Historical Society, residents refer to Kensington as “the place where the train still stops.”[10]

Footnotes

- ^ “Kensington B&O Railroad Station,” Clio.

- ^ Wilson S. Townsend, “Knowles Station and the Town of Kensington: 1870-1963,” The Montgomery County Story VII, No. 1 (The Montgomery County Historical Society, November 1963), 1.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Townsend, 2.

- ^ “Landmarks: Warner Manor,” Kensington Historical Society.

- ^ “History of the Town of Kensington,” Town of Kensington.

- ^ “Landmarks: Warner Manor,” Kensington Historical Society.

- ^ “History of the Town of Kensington,” Town of Kensington.

- ^ “Landmarks: Warner Manor,” Kensington Historical Society.

- ^ “Landmarks: B&O Train Station,” Kensington Historical Society.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)