The Flight and Flop of Washington's Rival Civil War Balloonists

To the President of the United States:

Sir:

The point of observation commands an area nearly 50 miles in diameter. The city, with its girdle of encampments, presents a superb scene. I have pleasure in sending you the first dispatch ever telegraphed from an aerial station, and in acknowledging indebtedness for your encouragement for the opportunity of demonstrating the availability of the science of aeronautics in the military service of the country.

T. S. C. Lowe[1]

The use of balloons in combat may seem odd with the technological advancements we have today, however, at the time that this telegram was sent, “aerial reconnaissance” was a new concept to the United States Army. Military leadership, including President Lincoln, saw the potential of military balloons, and the public believed they would change the landscape of the Civil War, aiding the Union’s eventual success. Only two years later though, what would be known as the “Balloon Corps” would be dissolved. So, what ended the use of this promising and successful aerial endeavor?

The egos of men.

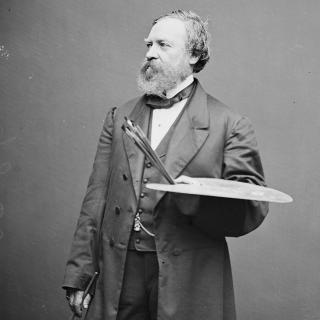

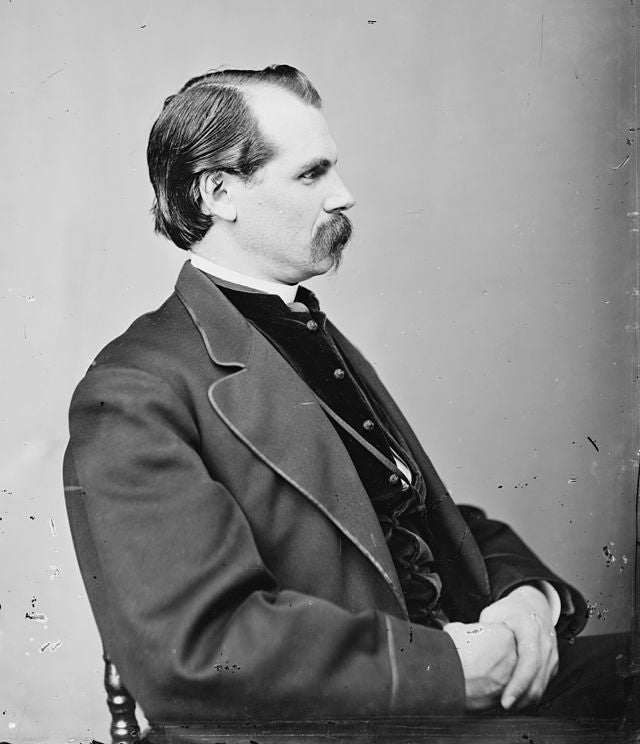

Enter: Thaddeus Sobieski Constantine Lowe.

In the years before the Civil War, “Professor” Lowe (a title many balloonists went by) had a career as an exhibition balloonist, earning him public acclaim. Lowe was an ambitious aeronaut, who had dreams of international and transatlantic flights. However, one of these flights in 1861 changed his perception of what ballooning could achieve. In a long-distance balloon trip beginning in Cincinnati that was intended to showcase his ability to complete a transoceanic flight, Lowe ended up in South Carolina, which was Confederate territory.[2] Local residents believed this well-suited man to be a Union spy and held Lowe hostage until he was able to convince them he had no military ties.[3] The captors eventually let the aeronaut go, but Lowe couldn’t help but wonder, what if he did work for the Union?

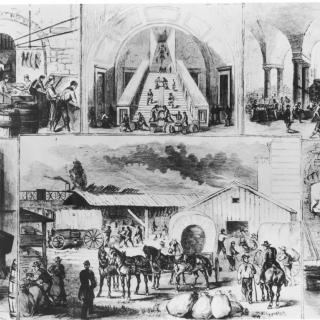

So, once he had returned to safety, he decided to offer his services to the War Department. Using his existing political connections, Lowe packed his balloons and made his way to Washington, hoping to demonstrate the aid ballooning could provide in military observations. Once he arrived, Lowe got the attention of various political officials, including President Lincoln. On June 18, 1861, with the encouragement of the Commander-in-Chief, Lowe made an ascension in his balloon, named Enterprise, on the grounds of the Columbia Armory (the current site of the National Museum of Air and Space!).[4] It was on this ascent that he sent that first telegram from an aerial station. President Lincoln was so impressed with this display of technological ingenuity that he had Lowe’s balloon towed from the Armory to the White House, where Lowe spent the night discussing the potential of reconnaissance ballooning with the President.[5] The next day, to the enjoyment of the public, Lowe made more ascents from the lawn of the Executive Mansion, taking political and military officials up in the air to see surrounding encampments.[6]

After his initial demonstration, Lowe’s ascensions continued to show the utility of military reconnaissance ballooning.[7] Union leadership wasn’t very familiar with Virginia geography, and with the aid of Lowe and his balloons, topographical engineers were able to make detailed maps of unknown Virginia roads and provide reports on Confederate encampments.[8] In addition to providing valuable intelligence to the Union, these balloon ascents also inconvenienced the Confederate army. Lowe made his balloons brightly colored and easy to spot to intimidate the Confederate troops, and it certainly worked. From the air, Lowe and his fellow aeronauts could see Confederate troops running for cover, or even changing direction in futile attempts to throw off aerial observations.[9]

Many of Lowe’s flights were centered around D.C., which lived in constant fear of Confederate invasion. With the aid of Lowe’s balloons, the Union brass was able to see Confederate movements up to 20 miles away, which was about as far as troops could travel in a day.[10] Therefore, with reports printed in local newspapers, Lowe was able to provide the public with the solace that they were safe – at least for the time being.

These impressive feats made Lowe somewhat of a local celebrity, popular with military leadership and the public alike. However, one man remained unimpressed with all of Lowe’s accomplishments.

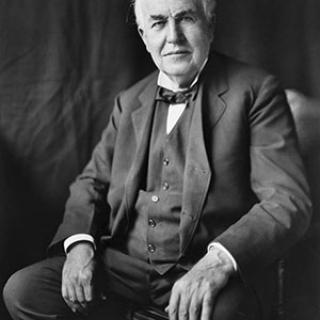

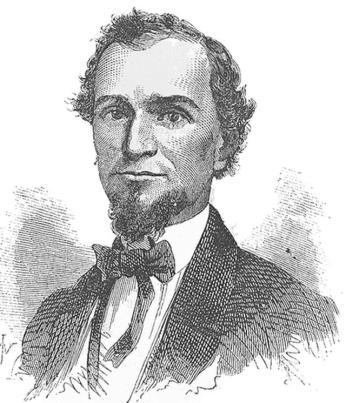

Enter: John La Mountain.

Much like Lowe, John La Mountain was a civilian aeronaut who understood the utility that balloons could provide the Union during the Civil War. On May 1, 1861, La Mountain offered his services to the War Department, and a month later received a reply from General Benjamin F. Butler who invited him to act as a contracted balloonist from Fort Monroe near Hampton, Virginia. Butler was intrigued by La Mountain’s advertised technological advancements, which the balloonist believed could be completed with a little military funding.[11]

While La Mountain and Lowe shared many similarities, La Mountain’s affinity toward taking risks set him apart. Most aeronauts, including Lowe, relied on tethered flights to make their observations. This meant that they had to have an additional crew who helped keep the balloon tethered to the ground while it ascended up to make observations. La Mountain on the other hand preferred to make untethered, free flights. He relied on an understanding of wind currents to carry him over Confederate territories to document enemy encampments before returning to Union bases.[12] These untethered flights also made La Mountain popular with the public, as he gained increased media attention for his risky endeavors.

By late summer in 1861, both Lowe and La Mountain had demonstrated great promise in the field of aerial technology for reconnaissance. But despite that, the War Department wasn’t exactly sure what to do with its balloonists. Command was passed from bureau to bureau, requiring each aeronaut to re-explain the military utility of their work – and justify the occasional accidents that came with ballooning – to new leaders.[13] For the most part, Lowe and La Mountain were successful at making their case to the military brass. However, they were unable to overcome another obstacle: an intense personal rivalry.

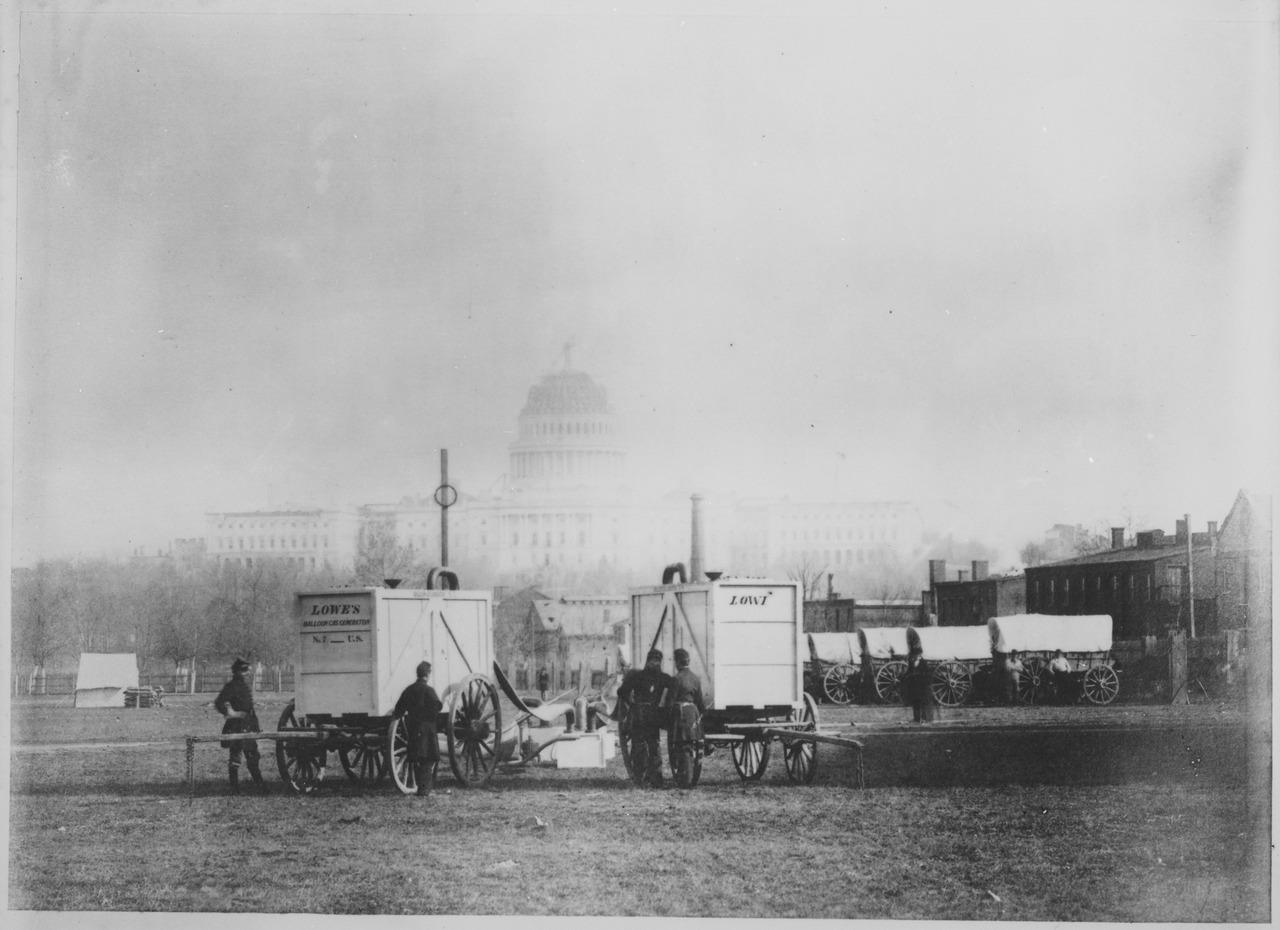

This rivalry predated the start of the War, but it increased in intensity once the two men were both flying for the Union Army. Lowe remained unimpressed with La Mountain, stating that he believed La Mountain to be “simply a balloonist” who did not have “the least idea of the requirements of military ballooning nor the gift of invention” which Lowe saw as integral to his own success.[14] Amongst other advancements, Lowe had invented portable gas generators that could be placed on wagons and used to fill balloons in remote locations.[15]

La Mountain was similarly dismissive of his rival’s accomplishments. Upon hearing about Lowe’s first telegram from an aerial station, La Mountain called it a publicity stunt, emphasizing his own strengths stating, “I have a simple method by which I can convey intelligence from above, without any expense whatever.”[16] He could also boast that he was the first to launch a balloon from a steamer ship – which he accomplished in August 1861 from the deck of the Fanny as it floated in the Chesapeake Bay, a feat that many historians consider to be the first use of an aircraft carrier in U.S. history.[17]

It was the army’s hope that these two men could put aside their differences for the good of Union, so in September 1861 General Fitz John Porter went to both Lowe and La Mountain to discuss a formal unification of the Balloon Corps. The three men met in Lowe’s tent at Fort Corcoran just outside of Washington, and it was decided that Lowe would be the new head of the Balloon Corps. Although he would cooperate with the Corps, when necessary, La Mountain would remain largely independent in his aeronautic pursuits.[18] General Porter left the meeting feeling as though the group had come to a successful conclusion, but in reality, this was the beginning of the end of the Balloon Corps.

Still acting as an independently contracted balloonist, John La Mountain continued his work making untethered flights over Confederate territory. However, his success was short-lived when his “best balloon” was lost thanks to high winds and an inexperienced crew. To continue his reconnaissance work, La Mountain needed a new balloon. While he wasn’t an official member of the Balloon Corps, he heard about Lowe’s storage warehouse in Washington where balloons were being kept for Lowe’s new crew of aeronauts.[19] As a fellow balloonist working in service to the Union, La Mountain felt that he should have access to these balloons. La Mountain appealed to Lieutenant Colonel J. M. Macomb, an engineer who oversaw the Balloon Corps, asking to use one of the balloons in storage. Macomb, in turn, ordered Lowe to share his balloons with La Mountain but Lowe refused, claiming that the balloons were needed elsewhere.[20]

La Mountain was astounded and claimed this was “all through motives of [professional] jealousy at my superior Reputation as an Aeronaut.”[21] A furious Lowe retorted that La Mountain was “a man who is known to be unscrupulous, and prompted by jealousy or some other motive, has assailed me without cause through the press and otherwise for several years…he has tampered with my men, tending to a demoralization of them, and, in short, has stopped at nothing to injure me…so much so that it is impossible for me to have any contact with him, as an equal in my profession, with any degree of self respect….” These harsh words, along with his refusal of Macomb’s order, led Lowe to be accused of insubordination.[22]

Through this altercation, Lowe lost some respect from military leadership, although was able to maintain his station as leader of the Balloon Corps. La Mountain was not so lucky. Despite his exhibited free-flight success, his insults towards Lowe and additional dramatics proved to be too much for military leadership. Macomb was frustrated, as was his superior officer, General George McClellan. McClellan, who was one of Lowe’s closest military allies, elected to solve the problem by cutting ties with La Mountain. So, on February 19, 1862, as a man without a functional balloon who had caused one problem too many, La Mountain was dismissed.[23]

In theory, La Mountain’s dismissal should have solved all of Lowe’s problems – his main rival had been removed and he had kept his position as the leader of the Balloon Corps. The victory was short-lived, however. Infuriated by the amount of time and energy expended to resolve their disputes, the unprofessionalism between the two aeronauts left a bad impression on new military officials who were looking for more structure with the Balloon Corps.[24]

One military leader that was looking to reign in the activities of the remaining aeronaut was Cyrus B. Comstock, who became Chief Engineer of the Army of the Potomac in 1862 and oversaw the Balloon Corps. General Comstock discovered that Lowe’s unprofessionalism didn’t end with his relationship with La Mountain. The balloonist had been mismanaging government funds. A showman at heart, Lowe had been paying for reporters to stay on Union bases, showing them around and taking them up on reconnaissance missions when he had the chance. This money was supposed to be going to Lowe’s extensive crew. His hired support included other aeronauts, some of whom went on strike after not receiving their pay on time and were subsequently dismissed by Lowe. Other crew members included repairmen, one of whom was Lowe’s father Clovis, who some accused Lowe of keeping on the government payroll even when Clovis was sick in Philadelphia.[25] Lowe’s unprofessional nature had been too much not only for his fellow balloon-men, but for the government. In an attempt to fall back into the good graces of the Union Army, Lowe offered to work without pay.[26] Unfortunately for him, this was not enough. After the Union’s failure at Chancellorsville, Lowe made multiple attempts to justify his military contributions. However, none of these appeals worked and the Balloon Corps was disbanded in 1863.[27]

Lowe was not alone in believing that balloon reconnaissance should have continued throughout the Civil War. Even Confederate leadership believed that getting rid of the balloons was a mistake. As officer Edward Porter Alexander admitted, "I have never understood why the enemy abandoned the use of military balloons…even if the observers never saw anything they would have been worth all the cost for the annoyance and delays they caused us in trying to keep our movements out of their sight."[28]

Perhaps if the two aeronauts had devoted the same amount of energy to observing the enemy as they had “to infighting and jockeying for a position they had”, their reconnaissance could have brought a quicker end to the War.[29]

Footnotes

- ^ Lincoln, Abraham. Abraham Lincoln papers: Series 1. General Correspondence. 1833 to 1916: Thaddeus S. C. Lowe to Abraham Lincoln, Sunday, Telegram from balloon. 1861.

- ^ Tom D. Crouch and Smithsonian Institution. The Eagle Aloft: Two Centuries of the Balloon in America. Smithsonian Institution Press, 1983, 344.

- ^ T. S. C. Lowe, “My Balloons in Peace and War: Memoirs of Thaddeus S.C. Lowe” (unpublished manuscript), 43.

- ^ “A Successful and Important Experiment,” Evening Star, June 19, 1861, sec. The News Here, 2.

- ^ Lowe, "My Balloons in Peace and War", 68-71.

- ^ “Balloon Ascension,” Evening Star, June 19, 1861, 3.

- ^ It is important to note that T. S. C. Lowe was not the first aeronaut who offered his services in support of the Union. James Allen and John Wise made early flights for the Union Army and were both selected ahead of Lowe in certain military endeavors. This was true for balloon reconnaissance in the First Battle of Bull Run, however, both Allen and Wise lost their balloons in this battle and in turn their individual military position. Allen, however, did join the Balloon Corps under Lowe in March 1862. See Crouch’s’ The Eagle Aloft, “Chapter 12, The Civil War Aloft: Origins” for more information on Allen and Wise.

- ^ Ballooning in the Civil War, 2014.

- ^ Crouch and Institution, The Eagle Aloft, 356.

- ^ Ballooning in the Civil War.

- ^ Crouch and Institution, The Eagle Aloft, 343.

- ^ “Military Aeronautics.,” Evening Star, December 4, 1861, sec. Our Military Budget.

- ^ Crouch and Institution, The Eagle Aloft, 362.

- ^ Lowe, My Balloons in Peace and War, 73.

- ^ Lowe’s invention was an important advancement for ballooning as Union balloons were filled with hydrogen, not hot air. Prior to Lowe’s invention, the balloons were filled at centralized locations and taken back and forth to the battlefield. With Lowe’s generators, the extra travel was no longer necessary. See Ballooning in the Civil War.

- ^ Crouch and Institution, The Eagle Aloft, 344.

- ^ Timothy Dennée, “John La Mountain and the Alexandria Balloon Ascensions,” Historic Alexandria Quarterly 2, no. 3 (Fall 1997), 2. Other historians credit Lowe with this accomplishment for his balloon launches from the ship the George Washington Parke Custis in November 1861 at the Washington Navy Yard.

- ^ Crouch and Institution, The Eagle Aloft, 364.

- ^ Crouch and Institution, 365.

- ^ Crouch and Institution, 367.

- ^ Dennée, “John La Mountain and the Alexandria Balloon Ascensions,” 8.

- ^ Crouch and Institution, The Eagle Aloft, 367.

- ^ Crouch and Institution, 368.

- ^ Crouch and Institution, 368-369.

- ^ Crouch and Institution, The Eagle Aloft, 405-406.

- ^ Ballooning in the Civil War.

- ^ Crouch and Institution, The Eagle Aloft, 414. Aeronauts such as James Allen and his brother Ezra attempted to continue the Balloon Corps after Lowe’s departure, but they lacked Lowe’s expertise and were unsuccessful.

- ^ Charles M. Evans, The War of the Aeronauts: A History of Ballooning During the Civil War (Stackpole Books, 2002), 294-295.

- ^ Crouch and Institution, The Eagle Aloft, 368-369.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)