Mary E. Surratt: The Woman Who Helped Kill Lincoln... Or Did She?

The first woman to be executed by the federal government of the United States wasn’t what you might expect. She was a matronly-looking, middle-aged mother of three. She was a widow and a devout Catholic who never missed mass. She was a quiet citizen who didn’t express any political opinions except for her belief that the “South acted too hastily” in seceding from the Union.1 She would not tolerate a drop of alcohol in her boardinghouse. She was a harmless and respectable lady, not one to conspire to kill a president. Or so people thought.

At the start of the Civil War, Mrs. Surratt and her husband lived in Southern Maryland, where they ran a tavern and the local post office at a small crossroads a couple hours by carriage outside of Washington, D.C., in an area which came to be known as Surrattsville. Most people living in that part of Maryland at the time were Rebel sympathizers and the Surratts were no exception. They owned a handful of slaves to work their land and Lincoln’s war sought to steal that property away. This prompted the family to use their control over the post office to facilitate a segment of the Confederate spy network, open their tavern to young Southern men on covert missions, and even allow their oldest son, Isaac, to join up with the army in Texas.

In 1862, John Surratt, master of the tavern and surrounding land, died, leaving Mary to care for the property and three children under the shadow of the immense debts left behind by her husband. To ease some of the financial burdens, Mary moved herself and her two younger children, John H. Surratt, Jr. and Anna, into a large house at 541 H Street in Washington and rented out the tavern to a man named John Lloyd to run while she took on boarders in the city. Almost immediately, Mary became embroiled in the plot which would take her life.

John Surratt, Jr., at about 19 years old, was deeply involved in Confederate activities in and around the capital. Using the boardinghouse as a center of operations, John began bringing home friends of various occupations: George Atzerodt, a blockade runner; Lewis Powell, a Baptist preacher or a laborer (depending on the day)2 , and, of course, John Wilkes Booth, the famous actor. These men often met privately at the boardinghouse, avoiding the curious ears of other inhabitants, such as Louis Weichmann, a school friend of John’s who worked in the War Department. Over the course of several months, Mary played hostess to a slew of shady characters and kept quiet about her son’s many travels to both Richmond and Canada.

Then came the fateful night of the 14th of April, 1865. The handsome actor who had so often graced Mary’s parlor did the unthinkable, leaving a trail of destruction and suspicion in his wake.

That night, officers came to the boardinghouse, demanding to know where Booth and John Surratt, Jr. were. Louis Weichmann answered the door, confused. Why did they want to know?

“Do you pretend that you do not know what has happened?” asked Detective Clarvoe. He pulled a piece of a cravat from his pocket, soaked in blood. “That is the blood of Abraham Lincoln.”3 Neither Booth nor Mary’s son was at the house, and the men eventually left.

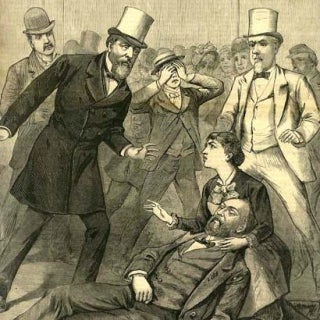

Right away, suspects and witnesses were arrested and stored in Old Capital Prison for questioning. On April 17th, two days after the night of the tragedy, police returned to H Street. Someone had tipped them off as to some odd activities going on there and the detectives had orders to arrest everyone in the house. As they were preparing to leave, a knock came at the door. Officers opened it to a large, dirty man with a pickaxe who seemed surprised to see them. Upon being questioned, he claimed to have been hired by Mrs. Surratt to dig a gutter and had come to ask what time he should arrive in the morning. Mary was called into the hall and asked to corroborate the story.

She raised her hand and swore, “before God, I do not know this man; I have never seen him.”4 Those words would come back to haunt her.

From the very beginning, newspapers across the country kept Americans informed about arrests, theories, and other news related to the assassination. Following Mary’s arrest, public sentiment rapidly condemned her. She was considered “the leading spirit next to Booth” and described rather uncharitably:5 “She was fifty years of age…Firmness and decision were part and parcel of her nature. A cold eye, that would quail at no scene of torture; a close, shut mouth, whence no word of sympathy with suffering would pass; a firm chin, indicative of fixedness of resolve; a square, solid figure, whose proportions were never disfigured by remorse or marred by loss of sleep.”6

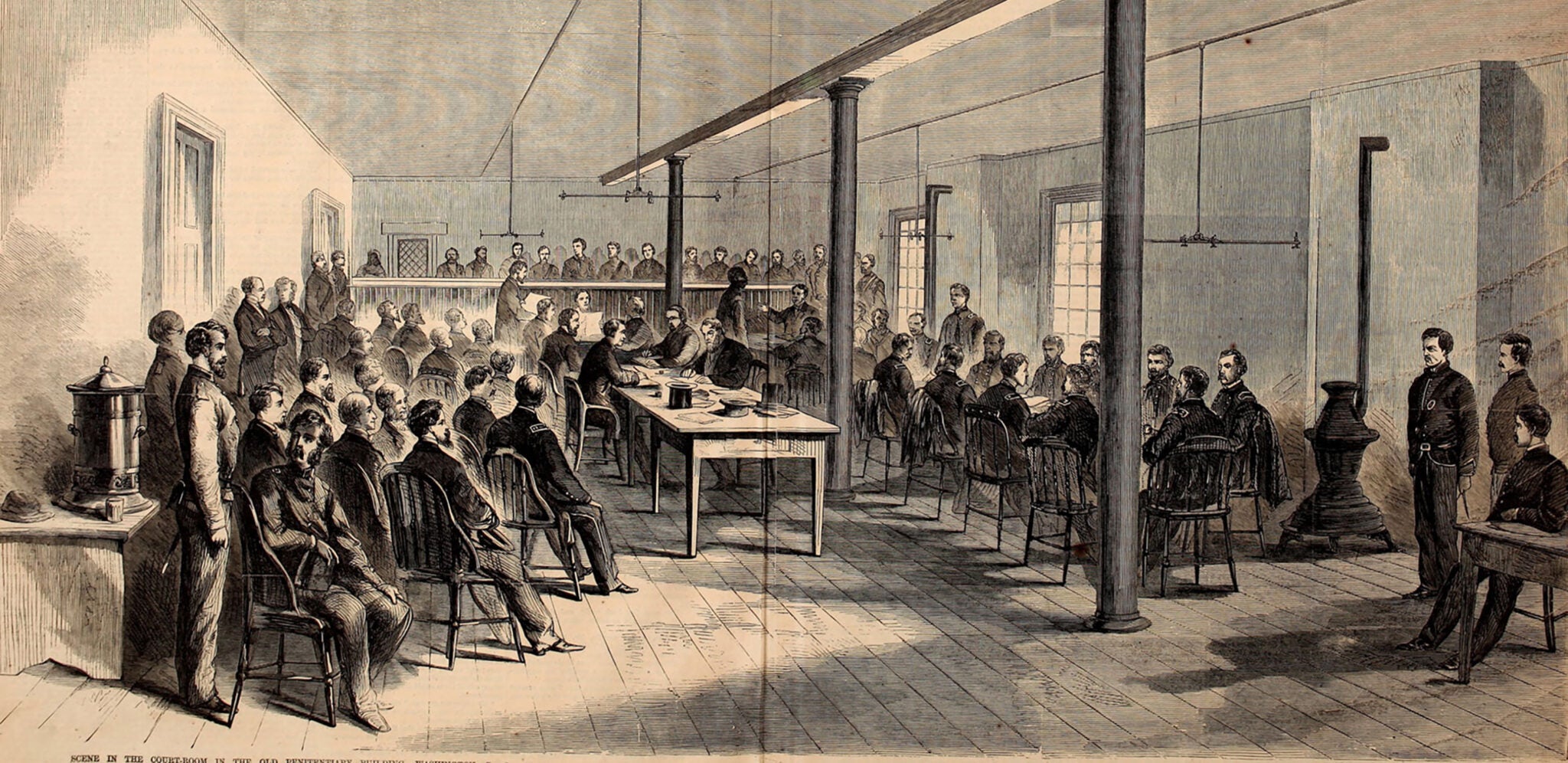

The trial of the conspirators began in mid-May, with seven men in the prisoners’ dock along with Mary. One of these was the man with the pickaxe, who had turned out to be Lewis Powell, the man who attempted the murder of Secretary Seward and who had visited the boardinghouse more than once.

The prisoners were charged with “maliciously, unlawfully and traitorously…confederating and conspiring together with one John Wilkes Booth” to kill the president and other high-ranking members of the United States government. Mary was additionally charged with “entertaining, harboring and concealing the conspirators, with full knowledge of their traitorous designs, and with aiding them and assisting them to escape.”7

Importantly, they were to be tried by military tribunal under the assumption that the assassination was an act of war and Washington, D.C. was under martial law. As historian Fred Borch has noted, this was a crucially important decision. "These Army judge advocates drafted the charges against the accused, selected the panel of Union officers to hear the case, served as prosecutors in the proceedings, advised the panel on the sufficiency of the evidence and the appropriate sentence, and ensured that those who had been sentenced to death were executed."8

The prisoners were given one day to obtain counsel before the trial began. Mary somehow managed to secure the services of Reverdy Johnson, former Attorney General and current United States Senator.

Johnson tried to get the trial moved to a civilian court, but to no avail. Authorities believed that no civilian jury could be impartial: Northerners were in a rage over the murder of their leader and Southerners celebrated the deed. General Ewing, representative of Dr. Mudd, another of the accused, observed, “Reason was swallowed up in patriotic passion, and a feverish and intense excitement most unfavorable to a calm, correct hearing.”9 So the trial began.

The courtroom was small and packed with spectators as soon as it was opened to the public. The witness stand faced the commission, with the prisoners and their lawyers to their left and back. If a witness turned to answer a question from the defense, they were sharply ordered to face forward, interrupting their testimony. Throughout the whole trial, all thirty-four of the prosecution’s objections were sustained, in marked contrast to only two of the fifteen made by the defense.10 The prosecutors themselves served as advisors to the military commission. The nine-man committee “rejected or admitted just such testimony as its judge-advocate [the prosecuting lawyer] declared should be admitted or rejected. Under such a procedure nearly all evidence having weight for the defense was, on one pretext or another, rejected; and all evidence that tended toward conviction, no matter how suspicious, was admitted.”11 Judge Advocates Holt and Bingham were even “active participants in the commission’s deliberations,” though they did not get to vote on the verdict or sentence.12 Additonally, there was no "presumption of innocence" in the military trial. 13

Over the course of the month and a half trial, over three hundred witnesses were interrogated and almost 5,000 pages of transcripts produced. Judge Advocate General Joseph Holt relied on two key testimonies in his prosecution of Mary Surratt, that of John Lloyd, the tenant of her tavern in Surrattsville, and that of Louis J. Weichmann, the young man who had boarded with her and worked at the War Department.

Weichmann testified to many secretive conversations between Mary and Booth, the movements of John Surratt, Jr., and two trips that Mary took to Surrattsville in the days leading up to the assassination. He spent days on the stand, swearing to evidence that would help condemn his landlady.

Lloyd corroborated Weichmann’s account of the trips to Surrattsville, where, the witnesses said, Mary told Lloyd to prepare some “shooting-irons” that her son had stored at the tavern and a couple bottles of whiskey. Some men would be coming for them the night of the 14th.14 That night, Lloyd said, Booth and his associate, David Herold, came for the guns and the liquor. In an interview with detectives, Lloyd cried, “Oh! Mrs. Surratt – that vile woman, she has ruined me.”15

Much was also made of Mary’s denial of recognizing Powell in her hallway. Defense lawyers claimed that her eyesight was exceedingly poor. The prosecution thought that a flimsy excuse for one of many lies she told police to protect other members of the plot.

On June 29, 1865, after seven long weeks in the suffocating courtroom, the members of the military commission retired to review the evidence and come to a verdict. On July 5th, they sent their findings and sentencing to President Andrew Johnson for approval. On the 6th, Mary, along with three of the men, was informed that she had been found guilty and was to be hanged the following day.

Mary’s supporters flew into action. They, along with the public, did not believe that the sentence would be carried out. The federal government had never hanged a woman before – surely it would not begin now. Five members of the commission even sent a recommendation for clemency to President Johnson, citing her “age and sex” and asking that he “commute her sentence to imprisonment in the penitentiary.”16 Two members of her legal team, Frederick Aiken and John Clampitt, petitioned Judge Wylie for a writ of habeas corpus, which he granted, ordering General Hancock, the jailer assigned to the prisoners, to present Mrs. Surratt before the civil court by 10am. The President immediately ordered the writ suspended, an authority which he had for the duration of the Civil War under the Habeas Corpus Suspension Act of 1863. Mary’s daughter, Anna, and Mrs. Stephen Douglas, the wife of the late senator, both went to the White House to beg for her life. Johnson would hear nothing in her defense.

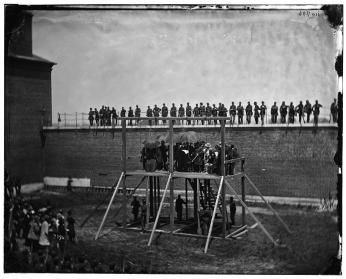

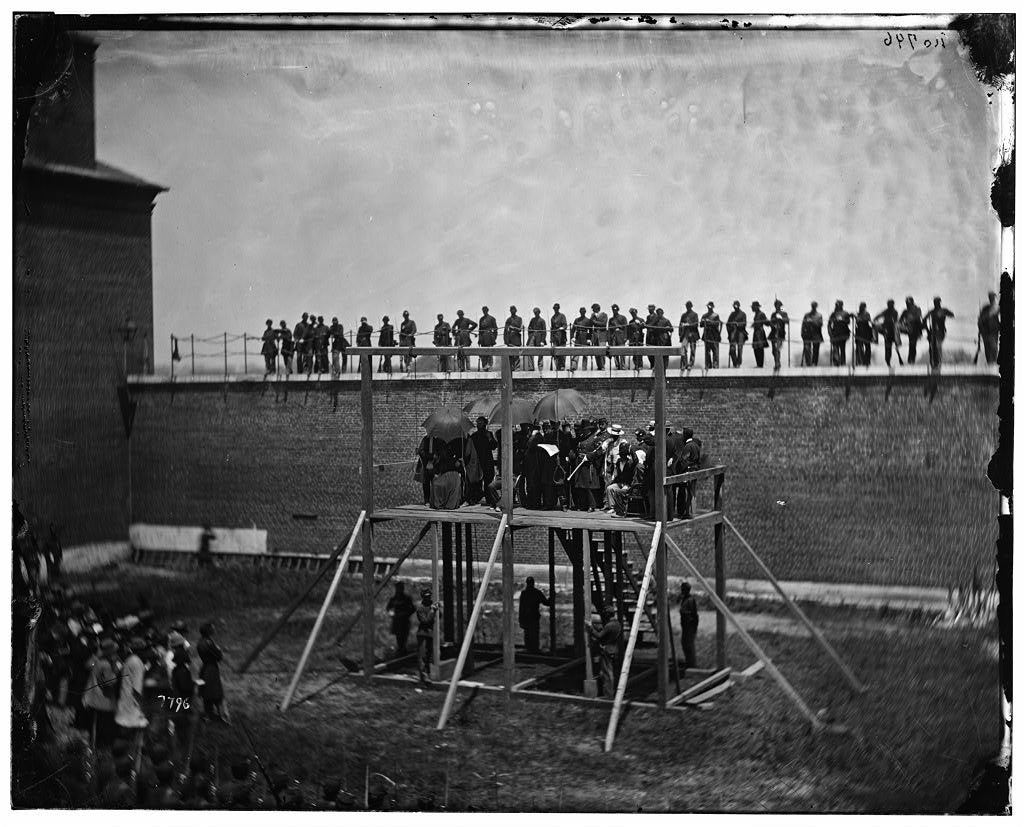

And so, in the early afternoon of July 7, 1865, Mary E. Surratt was led out to the scaffold. Her fear and grief were evident: “when taken from her cell to the scaffold, she had to be almost literally lifted and borne along by the officers.”17 General Hancock ordered soldiers on horseback to be ready along the route between the Old Arsenal Penitentiary and the White House to convey any last-minute reprieve. None came. At 1:30pm, the trap door on the scaffold dropped, and Mary left this world for the next.

At a speed to cause whiplash, public sentiment pivoted toward Mary. Shocked that the government would go through with hanging a woman, papers around the country suddenly declared her innocence, calling Weichmann a liar and Lloyd a drunk. Just three days after the hanging, the press was calling it “a day of eternal shame to the Republic” and making out the tribunal as an illegal and illegitimate court.18 Members of the military commission which condemned her were in turn condemned by the people. Anyone remotely involved with the case pushed the blame onto others. “One by one, the members of this court are trying to get away from responsibility in this case,” wrote one new supporter of Mary. “It is rather late in the day,” he said, for that.19

The case came up again in 1868 at President Johnson’s impeachment trial, where he claimed that he had never been given the commission’s recommendation for clemency. He blamed Judge Holt for keeping it from him, but multiple witnesses recounted his assertions that releasing Mary would encourage other women to become assassins, and that “if she was guilty at all, her sex did not make her any the less guilty.”20

But was she guilty? That’s the question that scholars and assassination buffs have wrestled with since July 8, 1865. Many have combed through Mary’s case, coming to various conclusions, but one widely held opinion is that if her trial were held today, Surrat's involvement might not be proved beyond a reasonable doubt. Much of the evidence and testimony presented by the prosecution is what a court would now consider circumstantial.21

Throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries, several books and articles defending Mary were published. David Miller DeWitt examined all of the evidence in “The Judicial Murder of Mary E. Surratt,” particularly noting the bias of the military commission. He observed that the nine Union combat veterans “came together with one determined and unchangeable purpose – to avenge the foul murder of their beloved Commander-in-Chief. They dreamt not of acquittal. They were, necessarily, from the very nature of their task, organized to convict.”22 DeWitt concluded that “The execution of Mary E. Surratt is the foulest blot on the history of the United States of America.”23

Almost 50 years later, Helen Jones Campbell published “The Case for Mrs. Surratt,” a dramatization of the whole affair which, though appearing to be thoroughly researched, is somewhat fast and loose with the facts (she doesn’t even record the ages of the Surratt children correctly).24 In 2011, the Lincoln Presidential Library, in partnership with the Illinois Supreme Court Historic Preservation Commission, staged a mock re-trial of Mary Surratt in which she was found not guilty. (You can watch a recording of that trial here.25 )

The current consensus, however, is that Mary Surratt had some knowledge of a plot to harm the President. It is difficult to believe that she could run her boardinghouse and interact with her son without knowing something of what was going on under her roof. Whether she knew that Booth’s plans had shifted from abduction to assassination is another question altogether and one we may never be able to answer. At the time of her trial, the accused could not testify on their own behalf, so no window into Mary’s perspective exists. She may have known that Booth meant to kill Lincoln on the night of April 14th, or she may only have known that some sort of Confederate scheme was underway.

In 1866, just one year after the trial and execution of the Lincoln conspirators, the Supreme Court ruled in Ex parte Milligan, a case which looked at the wartime trials of other Confederate sympathizers, that a military tribunal -- such as the one which considered Mary’s guilt -- was illegal and that civilians were to be tried only by a civil court when those courts were in operation.26 The next year, Congress passed the Habeas Corpus Act of 1867, restoring the authority of federal courts in issuing the writs and ending the special control granted to the president during the Civil War, another change which might have saved her. But all of this came too late for Mrs. Mary E. Surratt.

Footnotes

- 1 Kate Clifford Larson, The Assassin’s Accomplice: Mary Surratt and the Plot to Kill Abraham Lincoln (New York, NY: Basic Books, 2008), 106.

- 2 Lewis Powell also went by Lewis Payne and, on at least one occasion, Reverend Wood. He was a young and passionate Confederate who had fought with Mosby’s Rangers, escaped from a Union hospital, and posed as a civilian refugee. Newspaper coverage at the time referred to him as Lewis Payne, though that was just one of his several aliases.

- 3

Louis J. Weichmann, A True History of the Assassination of Abraham Lincoln and of the Conspiracy of 1865 (New York, NY: Vintage Books, 1977), 176.

- 4 “Conspiracy Trials: Proceedings of Friday - Further Interesting Evidence,” The Baltimore Sun, May 20, 1865.

- 5

“Official Order for the Trial of the Conspirators,” The Baltimore Sun, May 11, 1865.

- 6

“End of the Assassins,” The New York Times, July 8, 1865.

- 7

“The Charge and Specifications,” New Haven Palladium, May 16, 1865.

- 8

Borch, “‘Let the Stain of Innocent Blood Be Removed from the Land,’” 7.

- 9

David Miller DeWitt, The Judicial Murder of Mary E. Surratt (Baltimore, MD: John Murphy & Co., 1895), 17.

- 10 Borch, “‘Let the Stain of Innocent Blood Be Removed from the Land,’” 14.

- 11

John W. Clampitt, “The Trial of Mrs. Surratt,” The North American Review 131, no. 286 (1880): 230.

- 12

Borch, “‘Let the Stain of Innocent Blood Be Removed from the Land,’” 14.

- 13 Borch, “‘Let the Stain of Innocent Blood Be Removed from the Land,’” 14.

- 14

“Conspiracy Trials: Yesterday’s Proceedings - Conclusion of the Evidence for the Prosecution,” The Baltimore Sun, May 26, 1865.

- 15 “Conspiracy Trials: Yesterday’s Proceedings - Conclusion of the Evidence for the Prosecution.”

- 16

“Judge Holt and Mrs. Surratt,” The Baltimore Sun, August 27, 1873.

- 17 “End of the Assassins.”

- 18

“The Late Execution: Opinions of the Press,” The Baltimore Sun, July 10, 1865.

- 19

“Letter from Washington: Mrs. Surratt’s Execution,” The Baltimore Sun, August 28, 1868.

- 20 “Judge Holt and Mrs. Surratt.”

- 21

Kitty Felde, “‘The Conspirator’ Mary Surratt Still Haunts Washington,”LAist, April 25, 2011.

- 22 DeWitt, The Judicial Murder of Mary E. Surratt, 26.

- 23 DeWitt, 257.

- 24

Helen Jones Campbell, The Case for Mrs. Surratt (New York, NY: G. P. Putnam’s sons, 1943).

- 25

Re-Trial of Mary Surratt, American History TV (Chicago Public Library: Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum, 2011).

- 26 Borch, “‘Let the Stain of Innocent Blood Be Removed from the Land,’” 17.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)