When the Smithsonian Sent Alexander Graham Bell Gravedigging

On a gray morning just after Christmas Day, a scientist plods his way through frigid rain up to a cemetery overlooking the sea. Below, the Italian coast huddles close and faded beneath ice and clouds. But neither wind nor rain will deter the scientist from his mission: he is on his way to raise the dead.

This isn’t the opening to a Gothic horror novel, and the scientist isn’t Victor Frankenstein.

In fact, the man laboring through the winter slush is Alexander Graham Bell—inventor of the telephone—and he has come to Italy to bring the body of Smithsonian Institution founder James Smithson “home” to America before he’s blasted into the Mediterranean Sea.

Smithson, an English nobleman and minerologist, had bequeathed his fortune to create the Smithsonian Institution in America, despite having never crossed the Atlantic. He died in Genoa, Italy in 1829 and was buried in its British cemetery: a small but picturesque plot on the cliffs over the sea. The Smithsonian knew of its founder’s grave and participated in its preservation. The US Consulate had permission to care for the site, and two plaques were sent in Smithson’s honor. Beyond those formalities, though, Smithson was left alone.

Then in 1901, the Smithsonian Board of Regents received troubling news. Directly below the cemetery was a marble quarry, and the Italians were keen on expanding it. Dynamiting had begun, and eventually it would disturb James Smithson’s eternal rest by plunging the entire cemetery into the sea.1 If the Board wished to avoid that outcome, they should please come retrieve him.

Unfortunately, the Board didn’t consider it a priority. A transatlantic cadaver rescue would be expensive and time consuming, and the Smithsonian in 1901 had neither the money nor resources it does today. Only Alexander Graham Bell, who had recently been appointed regent, insisted that Smithson should have “an honored resting place beside the Institution he founded.” But as he told his wife, the proposition “received ONE VOTE—my own—and that was all.”2 He even offered to make the trip at his own expense, but the Board wouldn’t budge.

It took two years for Bell to finally convince his peers of their responsibility to rescue Smithson. Finally, in December of 1903, he was appointed as a one-person committee with a singular mission: disinter the remains of James Smithson from Italy and bring them safely back to their new home at the Smithsonian.

Alexander Bell and his wife Mabel Hubbard arrived in Italy on Christmas Day with little holiday cheer. Genoa was beset by gusts of wind and freezing rain. Their hotel, the Eden Palace, was hardly paradise: “a pink, luxurious resort in the summer,” but in the winter off season it left the Bells “drafty and exposed.”3 Mabel wrote of “hugging the steam register” in the lobby for warmth while the wind rattled the loose glass doors. Alexander had “caught cold” on the journey himself, and hoped to complete his mission quickly, “keeping indoors as much as possible.”

They visited Smithson’s grave in the British cemetery. Even amid the awful weather, it was picturesque: “a beautiful park of cypress trees whose dark foliage was relieved against the white marble paving and the pink and white chapel.”4 Of course, this peace was hampered by the quarry blasting, which had created a two-hundred-foot drop into rocks and spray. Already some of the coffins had “dislodged from their graves, tipped over, and crashed into the gaping void.”5 The sooner Smithson was out of the ground and everyone on their way home, the better.

Bell hoped to complete his mission quickly and quietly. There was no paperwork to worry about on the American side: shortly before leaving, the Treasury informed him that America had enacted no regulations “regarding the passage through customs of caskets containing the remains of persons.”6

Unfortunately the Italians did have regulations. Many regulations.

“There seemed to be no end to the red tape necessary to remove the body,” Mabel Bell wrote in her journal. “A permit to export the body beyond Italian limits, a permit to open the grave, a permit to purchase a coffin, permits from the National government, city government, the police, the officers, etc., etc.”7 Her husband listed them off with fatigue in his final report: a certificate of exhumation, a certificate for “regulation on Mortuary matters,” certificates from the American and British consulates, et cetera ad nauseum.8

Bell, who was nearing sixty and didn’t speak Italian, realized he was in over his head. He regretted not consulting a lawyer for "a legal opinion concerning the possible strength” of the United States’ claim to the bones.9 The last thing he needed was to be arrested for grave robbing.

Luckily, he had the support of William Bishop, the American consul in Genoa. Bishop helped tackle the monster of Italian bureaucracy, filing applications on Bell’s behalf and sliding matters along with officials. The unusual subject matter of the permits probably helped, too. “Very likely it was the only document of the kind in the office,” Bishop told Bell of an application to disinter the coffin. “I would guarantee them not to be so expeditious about ordinary affairs.”10

As if the paperwork weren’t enough to keep them busy, on New Year’s Day, the Bells woke up to a new problem, which “at first sight seemed insurmountable.” A clerk in the Mayor’s office had discovered an injunction filed years ago, which stated: “[Smithson’s] remains themselves cannot for any reason or by any person whatsoever be taken away or transported.”11 The Mayor then refused to let Bell touch the remains.

“It looks as if they hold the winning cards,” Mabel wrote to their daughter in exasperation. “We have all the permits. This morning they opened the grave.” But the injunction meant Smithson would be going nowhere. That morning her husband, dejected, told her: “I fear we may go home again without the body.”

“Won’t that be a sell!” Mabel wrote.12

The culprits were a French family—distant relations of Smithson—who had been trying for decades to wrest back some of his fortune. Having suffered a week of cold and wet Italian winter and not keen on prolonging his stay, Bell set about to get Smithson moving—by any means necessary.

Armed with copies of Smithson’s will and family tree, he marched into the Mayor’s office to prove his case. Not only was the family far removed from Smithson, he argued, but the injunction was decades old. Besides, if anyone owned the bones, it was the heir in Smithson’s will—the United States!

In case that weren’t enough, Bell claimed to be Teddy Roosevelt’s representative, hoping the President’s name would land with appropriate weight. This was a lie (Roosevelt wasn’t aware of the affair until later), but a helpful one. The thousand lira Bell gave to William Bishop quietly found its way to the pockets of relevant officials. That couldn’t have hurt, either, and the injunction was finally overruled.13

The Bells, Bishop, and a few witnesses climbed back to the crumbling cemetery to pack Smithson up for his trip. He was in good shape, which surprised Bell. “The skeleton was complete. The bones have separated but they did not crumble,” he noted. “In the passage of time the casket had crumbled to dust… which lay like a rug over the remains.”14

They transferred Smithson to a new metal casket, then a wooden coffin. Mrs. Bell placed a wreath of leaves in the coffin. Mr. Bishop covered the casket with the consulate’s seal and an American flag. “The flag adopts him already,” he said, “For our county, to which he has to long belonged in the spirit. He is now about to receive there a portion of the outward veneration and homage he so supremely merits.”15

But was he?

Even as Bell left Italy, there were no plans for a reception in America. In Gibraltar, Bell telegraphed his son-in-law Gilbert Grosvenor, then editor of National Geographic with the “hope [that] Smithson’s remains will be received with… much honor.” Currently, the Smithsonian had no plans in kind. Conferring briefly with the Smithsonian’s Secretary, Grosvenor took his case straight to the top.

“As the time is urgent I take the liberty of addressing you directly,” he wrote to President Roosevelt. He asked for a Navy vessel to accompany Smithson from New York to Washington, and a military escort when he reached the city. “This official tribute from the American nation seems due a man who bequeathed his entire fortune to a people whom he had never seen.”16

Roosevelt did not respond directly, but within the week, Grosvenor was in command of a tiny army: a warship, fifty cavalry, a handful of navy officers, and the Marine Corps Band. The USS Dolphin met the Bells and Smithson in Hoboken, New York, where it carried the casket to Washington while Alexander and Mabel Bell went ahead by train. When the Dolphin arrived at Navy Yard, marines in neat dress uniforms would transfer the coffin to a caisson. Then, surrounded by a cavalry squadron, it would drive in procession to the Smithsonian Castle, where Bell would officially deliver James Smithson to the Institution he created.

As fate would have it, Alexander Graham Bell nearly didn’t make it to his own ceremony. The inventor notoriously worked on a near-nocturnal schedule, and returned to it as soon as he was back in DC. On the morning Smithson arrived, only hours after Bell had gone to sleep, a servant named Charles Thompson came up with breakfast and newspapers. It was time for Bell to escort Smithson’s remains to their new home, and he couldn’t wait “another minute.”

“What are you talking about?” Bell asked. “He’s been dead for fifty years.”

“Can’t help it, sir,” Thompson said. “He’s in Washington now and you brought him here.”

A moment of grumpy silence followed, before Bell said, “Why did he come to bother me?”17

It took Mabel Bell’s persuasion to get her husband into his formal suit and bundle him out to Navy Yard to finish the job he had so insistently volunteered for in the first place.

On January 25, 1904, Smithson finally reached his new home. At a “brief but impressive” ceremony, Bell formally handed over the remains of his fellow scientist to the institution he founded.18 In a short speech, Bell thanked the American and British consuls for their help and presented the Board of Regents with the remains. “My mission is ended,” he said—and not a moment too soon!

For the Board of Regents, Senator William Frye accepted the remains of the “distinguished founder.” At the Smithsonian, he said, “[Smithson’s] grave here will be an incentive to earnest, faithful, wise. and discreet endeavor to carry out his lofty purposes, and, sir, it will be to our people a sacred spot while the Republic endures.”19

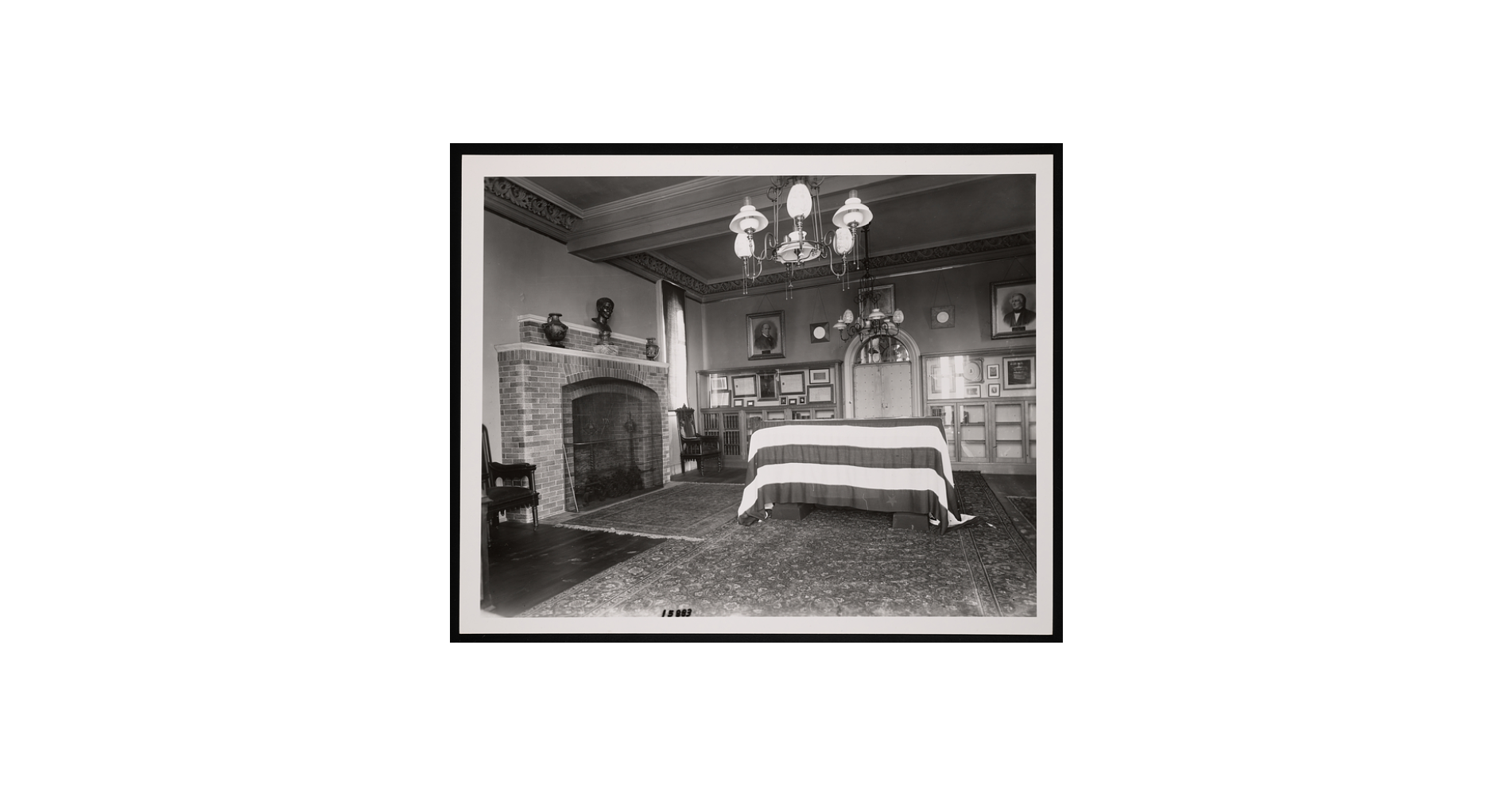

That grave would take a while to materialize, going through a number of proposals from garden gravesites to vaults to a monument several times larger than the Lincoln Memorial.20 While the Board waited for money from Congress, Smithson’s coffin lay in state in the Castle’s South Tower amid his other belongings, draped with British and American flags.21

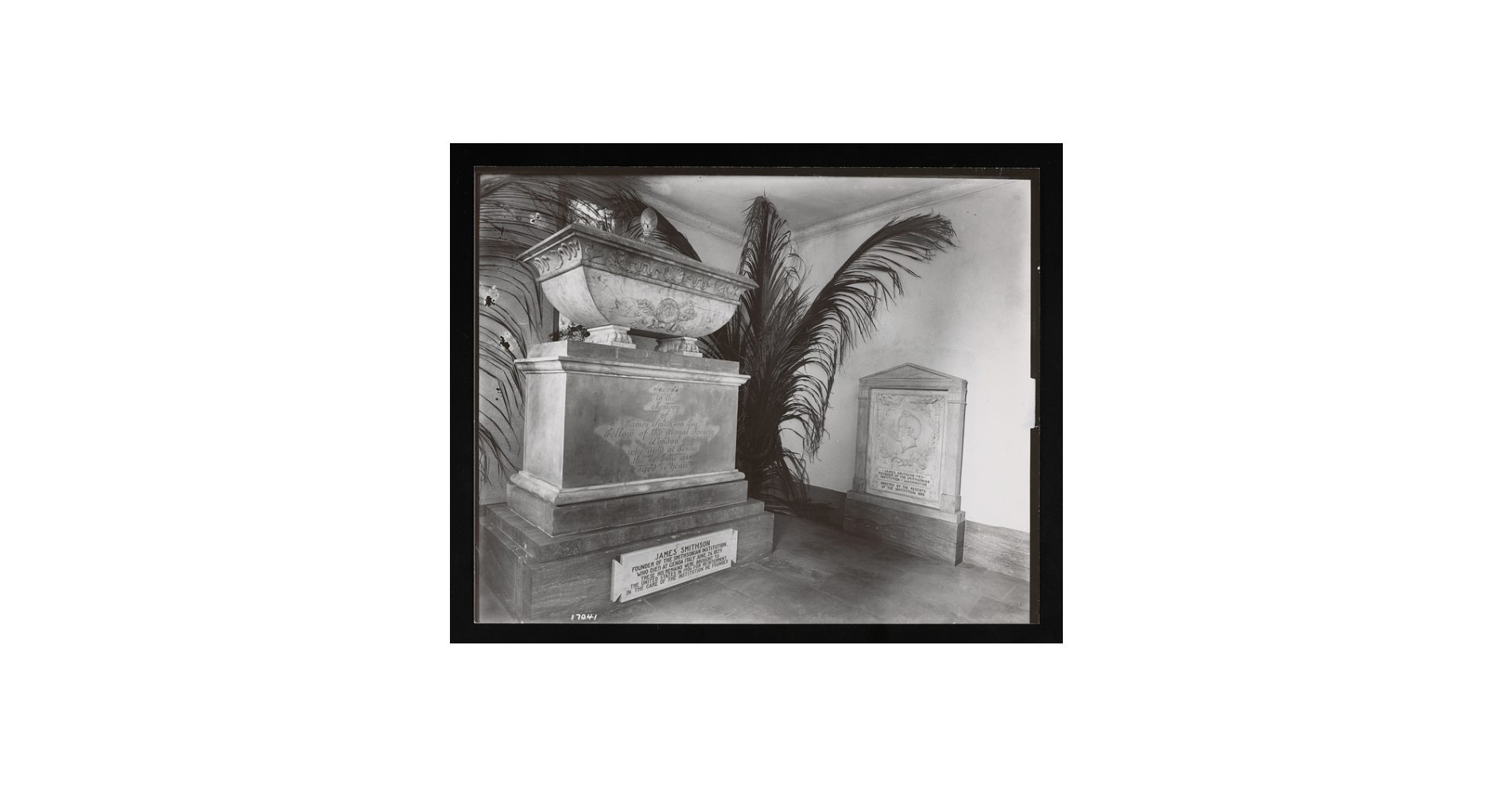

After nearly a year of keeping poor Smithson in limbo and no Congressional money appearing, the Board of Regents decided to build a tomb “in some proper position… in the grounds of the Institution.”22 They remodeled a janitor’s closet in the Castle into a mortuary chapel with stained glass windows and dark marble floors. The Board sent for the grave marker Bell had left in Italy, as well as iron fencing from the original cemetery, which were incorporated into the tomb and turned into a gate. James Smithson was finally laid to rest on March 6, 1905, in the Smithsonian Castle, where he remains today.

If you go to visit Smithson, remember to bend down! Many visitors assume he’s laid in the ornate urn. In fact, he’s down at your feet! The front of the brownstone base is removeable, and Smithson was “slid in” on the day of his entombment. You may also notice a moth carved into his grave marker. This symbol is a tribute to Smithson’s legacy. After one death, life flourishes again in a new form: the vibrant Smithsonian Institution that has flourished around Smithson in the century since his entombment.23

Footnotes

- 1

Niekrasz, Emily. ““The Proper Thing to Do": James Smithson’s Journey to Washington.” Smithsonian Institution Archives, June 27, 2019.

- 2 The Stranger and the Statesman: James Smithson, John Quincy Adams, and the Making of America’s Greatest Museum. New Word City, 2015. p. 11

- 3 The Stranger and the Statesman: James Smithson, John Quincy Adams, and the Making of America’s Greatest Museum. New Word City, 2015. p. 1

- 4 The Stranger and the Statesman: James Smithson, John Quincy Adams, and the Making of America’s Greatest Museum. New Word City, 2015. p. 8

- 5 The Stranger and the Statesman: James Smithson, John Quincy Adams, and the Making of America’s Greatest Museum. New Word City, 2015. p. 3

- 6 The Stranger and the Statesman: James Smithson, John Quincy Adams, and the Making of America’s Greatest Museum. New Word City, 2015. p. 5

- 7

Burleigh, Nina. “Digging Up James Smithson.” American Heritage, 2012.

- 8

Bell, Alexander Graham, Samuel P Langley, and James Smithson. Letter from Alexander Graham Bell to Samuel P. Langley. 1904. Manuscript/Mixed Material.

- 9 The Stranger and the Statesman: James Smithson, John Quincy Adams, and the Making of America’s Greatest Museum. New Word City, 2015. p. 5

- 10

Bell, Alexander Graham, Samuel P Langley, and James Smithson. Letter from Alexander Graham Bell to Samuel P. Langley. 1904. Manuscript/Mixed Material.

- 11

Bell, Alexander Graham, Samuel P Langley, and James Smithson. Letter from Alexander Graham Bell to Samuel P. Langley. 1904. Manuscript/Mixed Material.

- 12 The Stranger and the Statesman: James Smithson, John Quincy Adams, and the Making of America’s Greatest Museum. New Word City, 2015. p. 7

- 13

The Hungerford Deed, Heather Ewing and William Bennett, Sidedoor, podcast audio, April 2022.

- 14

Burleigh, Nina. “Digging Up James Smithson.” American Heritage, 2012.

- 15

Annual Report Of The Board Of Regents Of The Smithsonian Institution. Vol. 1904. Washington: Smithsonian Institution, 1904.

- 16

Annual Report Of The Board Of Regents Of The Smithsonian Institution. Vol. 1904. Washington: Smithsonian Institution, 1904.

- 17 The Stranger and the Statesman: James Smithson, John Quincy Adams, and the Making of America’s Greatest Museum. New Word City, 2015. p. 10

- 18

Annual Report Of The Board Of Regents Of The Smithsonian Institution. Vol. 1904. Washington: Smithsonian Institution, 1904.

- 19

Annual Report Of The Board Of Regents Of The Smithsonian Institution. Vol. 1904. Washington: Smithsonian Institution, 1904.

- 20

Stamm, Richard. “The Search for a Proper Memorial.” Smithsonian Institution. Smithsonian AHHP Division, 2008.

- 21

Stamm, Richard. “James Smithson’s Italian Grave Site.” Smithsonian Institution. Smithsonian AHHP Division, 2008.

- 22

Annual Report Of The Board Of Regents Of The Smithsonian Institution. Vol. 1904. Washington: Smithsonian Institution, 1904.

- 23

Stamm, Richard. “Smithson’s Crypt.” Smithsonian Institution. Smithsonian AHHP Division, 2008.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)