A Tale of Two Painters: Theodore Roosevelt's Portraits

In her official portrait as First Lady, Edith Roosevelt appears regal yet graceful. She wears a long white dress and a stylish black coat, with a frilly shawl draped around her shoulders. In one hand she holds a pair of silky gloves, and in the other, an elegant cane. She is poised comfortably upon a bench in the White House grounds, a rainbow of pastel colors bringing the background to life. Beneath her hat, a small smile plays upon the First Lady’s face as she looks into the distance.

Mrs. Roosevelt’s portrait was created by the renowned French artist Théobald Chartran in 1902.[1] Throughout France and the United States, the painting was met with great public acclaim.[2] He had successfully portrayed Edith Roosevelt: she was a strong, thoughtful woman, though with a certain kindness in her eyes that came from being a devoted mother.[3]

Unsurprisingly, then, President Theodore Roosevelt wanted a portrait of himself that was equally as flattering. But, in truth, he was not the most pleasant subject to paint—as could be confirmed by two separate portraitists.

President Roosevelt was a man with an extraordinary personality. He was in part kind, charming, and enthusiastic about life; but he was also a man of power, with a commanding presence and resolute disposition.

Chartran returned to Washington on January 21, 1903,[4] and arranged to paint the president, tasked with portraying both areas of his complicated character.[5] Judging from Chartran’s past work, Roosevelt was probably looking forward to receiving a well-crafted portrait of himself; but as he watched the painting gradually take shape, he was appalled.

Writing in a letter to his son, Kermit, Roosevelt professed coldly, “Chartran has been painting my picture. I do not particularly like it.”[6]

Chartran finished his portrait of Roosevelt in the early days of February. But when completed, the person in his painting was not the exuberant, proud, nature-loving man that America had elected as its 26th president. Rather, he looked powerless and dainty, according to the Roosevelt family. Jokingly, and to the president’s dismay, they nicknamed the portrait “the mewing cat.”[7] Nonetheless, it was sent off, to be exhibited throughout France.

At this point, Roosevelt likely felt frustrated. He’d sat for an artist for several stretches of time in the past weeks, despite his ever-busy schedule—and the final product was not worth it.[8]

But before he could put the matter from his mind, Roosevelt was reminded that the White House was expecting yet another portraitist in the coming days: John Singer Sargent. In fact, the President himself had invited him, many months before.

In 1902, Roosevelt had started thinking about who he wanted to paint his official presidential portrait. Sargent’s reputation made him a clear choice: he was an American expatriate artist who had plenty of experience painting leading figures (including barons, company leaders, and the like),[9] and he was praised for his ability to “[see] beneath the surface” of his sitters.[10] Roosevelt had written to Sargent, stating:

“It seems to me eminently fitting that an American President should have you paint his picture.”[11]

At the time, the president probably didn’t know how much he would despise having his portrait done. But the plan was set.

Sargent arrived at the White House on February 11, 1903, just days after Chartran departed. He took a walk with Roosevelt around the premises, searching for the ideal location to conduct the painting. Sargent, a seasoned artist, understood how to properly stage a portrait: he decided to have Roosevelt pose somewhere indoors, and looked for ways to demonstrate his passion for nature, his “rugged strength,” his identity as a politician, and his personable side, all at once.[12]

Roosevelt was not having it. The president did not like following the instructions of others. He did little to hide his impatience as Sargent led him from room to room, constantly pausing to have Roosevelt pose, or shaking his head at insufficient light sources and backdrops.

The tension built between the pair as the tour of the White House continued. Bickering like schoolboys, Sargent and Roosevelt could not agree on a place to set the painting. As they climbed the stairs to search for a location on a higher floor, Roosevelt bitterly alleged that Sargent didn’t actually know what he wanted.

Affronted, Sargent replied that Roosevelt didn’t know how to pose.

Roosevelt furiously swung around on the landing, grabbed the newel-post of the railing, threw a hand on his hip, and yelled, “Don’t I!”

But in that moment, Sargent had seen the perfect pose. He told Roosevelt not to move—they had finally found the location of their portrait.[13]

Over the course of the next week, Sargent painted Roosevelt at this spot whenever he could get him to stay still. He had a very tough time doing so. Roosevelt’s schedule was inflexible, and he constantly found excuses to leave the White House. He preferred to keep himself busy, refusing to sit for Sargent for more than thirty minutes at a time (usually after lunch).[14] When Roosevelt did comply, he was restless, a multitude of other things on his mind.[15]

What with Roosevelt’s commanding and difficult personality, Sargent would later say that in his time at the White House, he often felt like a “rabbit in the presence of a boa constrictor.”[16] Nevertheless, the artist finished the painting on February 19, 1903, just over a week after he had started.

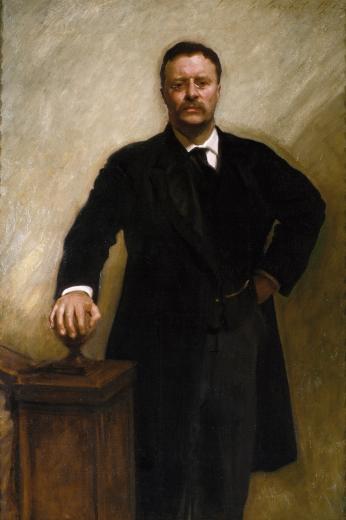

Amidst a grey-gold background, Roosevelt stands proudly in the center of the portrait, his left hand poised on his hip, and his right hand placed firmly upon the newel-post of the stairwell. Though the painting uses no props to indicate his position as an outdoorsman, a statesman, or even a president, Roosevelt is displayed as a complicated, bold, yet truthful character. As noted in a New York Times article, the portrait does not quite capture the “genial side of the President,” but rather his alertness and distinct energy, his attitude when in “the mood of fierce discussion, his lips still quivering with speech, his eyes narrowed behind the glasses in a watchful gaze.”[17]

It was perhaps impossible for Sargent to truly encapsulate every overlapping aspect of Roosevelt’s dynamic personality, or to include a nod to his every interest. But Roosevelt’s portrait has remained iconic amongst the other presidential portraits throughout the years, showcasing a man who was resolute and sharp, albeit difficult at times. The painting is simultaneously simple and striking.

But how did the president like his newest portrait?

“I like his picture immensely,” he wrote after seeing the finished product.[18]

Indeed, Roosevelt’s irritation quickly ebbed away when Sargent showed him the painting. It was marvelous. The piece hung first in a private gallery in Washington, D.C., but returned to the White House by the end of March, where it was displayed as Roosevelt’s official presidential portrait, and enjoyed by the president and his family.[19]

Roosevelt was thrilled with the portrait Sargent had created for him, and he would cherish it for the rest of his life. For him, it was the end-all and be-all of portraits. And so, when asked to sit once again for another artist not six months after Sargent bid him goodbye in 1903, President Roosevelt wrote adamantly:

“Upon my word… After Sargent painted his portrait I registered a vow that I was through with sitting for any more portraits.”[20]

And in case you were wondering what became of Chartran’s “mewing cat” portrait, after an extended tour of France, it came back to the White House. The Roosevelts promptly hung it in the darkest corner of a back hallway, avoiding it at all costs. Six years later, Roosevelt ordered that the painting be removed from the building and burned.[21] Though no word exists about whether Chartran ever discovered that Roosevelt hated his piece, he did politely admit in an interview with the Washington Post that, at the time that he was creating it, “it was difficult to get the President to sit still; I never had a more restless or more charming sitter.”[22]

Footnotes

- ^ The French Ambassador commissioned Chartran to paint the portrait of Mrs. Roosevelt as a gift to the president shortly after he entered office. Her portrait was such a success that the family asked him to create one of Miss Alice Roosevelt, too, which was just as successful. See: Allison McNearney, "Theodore Roosevelt Hated His Presidential Portrait So Much He Burnt It," Daily Beast, last modified February 16, 2018, https://www.thedailybeast.com/theodore-roosevelt-hated-his-presidential-portrait-so-much-he-burnt-it.

- ^ "Art Notes," The Evening Star (Washington, DC), August 23, 1902, 18.

- ^ "Guests of President: Small Company Entertained at White House Dinner: Notable Portraits on View," The Washington Post (Washington, DC), March 15, 1902, 7.

- ^ "A Portrait of the President," The Evening Star (Washington, DC), January 21, 1903, 1.

- ^ The painting appears to have been mutually desired by both the Roosevelts and also Chartran, himself, who hoped to exhibit the president’s portrait alongside that of Miss Alice Roosevelt. See: "Topics in New York: Chartran Cannot Show Portrait," The Baltimore Sun (Baltimore, MD), January 19, 1903, 10.

- ^ Theodore Roosevelt to Kermit Roosevelt, "Letter from Theodore Roosevelt to Kermit Roosevelt," February 1, 1903, https://www.theodorerooseveltcenter.org/Research/Digital-Library/Record/ImageViewer?libID=o280360&imageNo=1.

- ^ Michael R. Canfield, Theodore Roosevelt in the Field (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015), 6.

- ^ "A Portrait," 1.

- ^ Canfield, Theodore Roosevelt, 6.

- ^ Leila Mechlin, "The North Window," The Evening Star (Washington, DC), April 23, 1925, 6.

- ^ Theodore Roosevelt to John Singer Sargent, "Letter from Theodore Roosevelt to John Singer Sargent," May 13, 1902, https://www.theodorerooseveltcenter.org/Research/Digital-Library/Record/ImageViewer?libID=o182228.

- ^ Canfield, Theodore Roosevelt, 6-7.

- ^ This is the version of the story as recalled by usher Isaac Hoover. See: Canfield, Theodore Roosevelt, 7; James G. Barber, Theodore Roosevelt: Icon of the American Century (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, 1998), 48-50; Edward G. Lengel, "The Art of John Singer Sargent in the White House," The White House Historical Association, last modified June 27, 2017, https://www.whitehousehistory.org/the-art-of-john-singer-sargent-in-the-white-house.

- ^ Barber, Theodore Roosevelt, 50.

- ^ Canfield, Theodore Roosevelt, 7-11.

- ^ Ibid., 10.

- ^ "Roosevelt's New Portrait," The New York Times (New York), March 23, 1903, 8.

- ^ Theodore Roosevelt to Kermit Roosevelt, "Letter from Theodore Roosevelt to Kermit Roosevelt," February 19, 1903, https://www.theodorerooseveltcenter.org/Research/Digital-Library/Record/ImageViewer?libID=o280363&imageNo=1.

- ^ James Henry Moser, "Art Topics," The Washington Post (Washington, DC), March 29, 1903, 4.

- ^ Theodore Roosevelt to James Sullivan Clarkson, "Letter from Theodore Roosevelt to James Sullivan Clarkson," August 7, 1903, https://www.theodorerooseveltcenter.org/Research/Digital-Library/Record/ImageViewer?libID=o185618.

- ^ White House, "Art for the President's House--An Historical Perspective," The White House (archive), https://clintonwhitehouse4.archives.gov/WH/glimpse/art/html/presart12.html.

- ^ "President Was Restless: Chartran Talks About His Experience While Painting Portrait," The Washington Post (Washington, DC), April 25, 1903, 1.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)