When the Swamp Wasn't Drained: How a Con Man Tried to Build the World's Largest Airport in Alexandria

Huntley Meadows Park near Alexandria treats visitors to over 1,500 acres of restored wetlands, forests, and meadows. It is home to a stunning diversity of wildlife, all visible from a boardwalk, observation tower and trails. But if Henry Woodhouse, an aviation enthusiast with a shady past, had gotten his way, this gorgeous slice of Northern Virginia might have become the biggest airport in the world.1

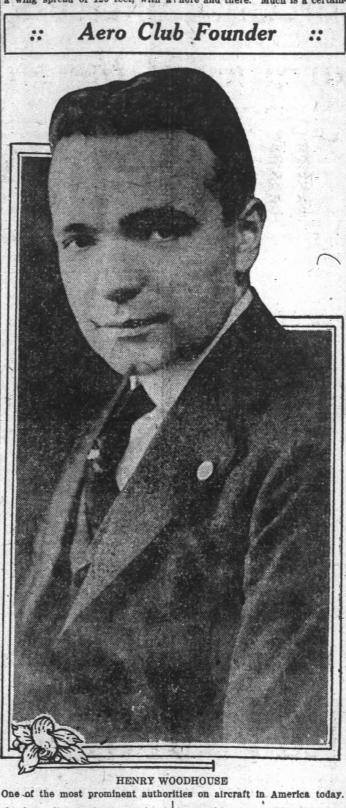

Trouble seemed to follow Mario Terenzio Enrico Casalegno, or Henry Woodhouse as he would come to call himself, all the way from his homeland of Italy to the United States. In a restaurant kitchen where he worked in Troy, New York, Woodhouse stabbed a fellow cook and then claimed the man had fallen on the knife he was using during an argument. After serving over four years in prison for first-degree manslaughter, Woodhouse decided to pursue a far less risky career upon his release in 1908.

He began making a name for himself in the fledgling world of aviation, for which he had developed a passion in Europe prior to his arrival in the US. He wrote articles that appeared in prominent periodicals, published textbooks on military aviation, joined and led aeronautics organizations, and made friends in high places along the way. One of these friends was Robert J. Collier, heir of the Collier publishing empire, and the namesake of the Robert J. Collier Trophy, the highest honor in aviation.

Aviation wasn’t just a hobby to Woodhouse, though. He was soon recognized as a leading expert and advocate of his time. He believed in aviation’s transformative power.2 In a 1912 letter to journalist Ida Tarbell, he wrote, “It is a spiritual discovery to look down upon the earth, on this checkered, uneven carpet on which our ancestor crowled [sic] for millions of years and see human monuments – and such pillars of civilization as churches, schools and banks – looking like toys. It is an experience unlike any other.” He concluded, “Meantime, if you find anybody who doesn’t see anything in life or wastes life in some mechanical system of eat, sleep and make believe – just urge a flight. That will cure it.”3

Yet, it wasn’t long before cracks in his reputation began to appear. Woodhouse contributed to infighting and factionalism within the Aero Club of America, the leading aviation organization in the US, which he joined in 1911. He was viewed as a crony of the Club’s leadership, and treated distinguished guests, including members of Woodrow Wilson’s diplomatic corps, with hostility. He harshly criticized organizations to which other Aero Club members belonged.

Around this time, Woodhouse also seemed to develop a penchant for lawsuits, which became a favorite pastime for the remainder of his life. He lost a major lawsuit he had filed to prevent the Aero Club’s merger with the American Flying Club.4 Amidst investigations into financial impropriety involving the Club, Woodhouse’s old murder conviction came to light in an exposé published by The New York Evening Post.5 With his criminal past laid bare, and with the reputation of the once esteemed Aero Club diminished, the aviation world moved on without him. Woodhouse still published articles, but he would never again see the fame that the 1910s had brought him.

From the 1920s onward, Woodhouse engaged in a series of misadventures that would come to define his peculiar life. After a lifetime of being an actual Italian, rebranding himself as an American, hiding the fact that he was a convicted murderer, and gaining then losing respect as an aviation expert, Woodhouse still had a few more identities to try on. Throughout the 1920s and 30s, he became a master forger, and made a living by collecting historical artifacts and documents, forging signatures of the signers of the Declaration of Independence, and displaying them in a Manhattan museum gallery. He sold some of them at a department store and through public auctions. This was more than a sudden career change for him. American history was Woodhouse’s defining passion besides aviation, especially history surrounding George Washington.

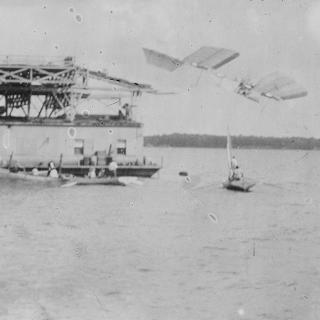

In 1928, Woodhouse attempted to combine his passions when embarking on his greatest misadventure of all. He purchased 166 acres of dairy farmland in Alexandria, Virginia’s Hybla Valley, the first of several parcels of land he planned to combine and then construct the largest airport in the world. The George Washington Air Junction was to become a base for trans-Atlantic plane and Zeppelin flights. Nowadays Zeppelins might be consigned to the realm of steampunk art and alternate history fiction, but in the early 20th century they were considered a legitimate form of aerial transportation.

A ceremonial planting of surveyor’s stakes occurred in January 1929, kicking off Woodhouse’s surveys for his runways. The stakes were planted by Wilson Seden Washington, a descendant of George Washington’s brother, John Augustine Washington. Woodhouse boasted that the East-West runway would be 7,500 feet long, and the North-South runway 3,000 feet long, making them the longest in the world, all so that the largest aircraft could have taken off and landed safely.6

The George Washington Air Junction was dedicated on February 22, 1929, in a ceremony attended by Wilson Seden Washington, his daughter Nancy James Washington, Professor Albert Bushnell Hart, a historian, William Tyler Page, a clerk of the House of Representatives, and a crowd of Alexandria and D.C. residents. The name George Washington Air Junction was announced by Seden Washington, after which his daughter Nancy pressed a switch illuminating a 50-foot arch standing over the entrance to the airport site.

In a speech, Professor Hart justified the airport’s name by describing George Washington as a believer in aviation, having taken an interest in the first manned balloon flight, which occurred on January 10, 1793. Hart went on to describe the planned airport as, “a great aerial, scientific and historic center, supplying to the Capital of the United States.”7

In pushing a new airport, Woodhouse stepped into an evolving situation. D.C. was already serviced by Hoover Field and Washington Airport, but these were small and notoriously dangerous airfields. They merged in 1930 to become the Washington-Hoover but it didn’t last beyond 1941.8 Meanwhile lawmakers on Capitol Hill were starting to push for a new modern airport at a site closer to the District.

Nonetheless, Woodhouse pushed ahead in Hybla Valley. To supplement his original land purchase, he bought an additional 1,200 acres of farmland in June 1929. In total, Woodhouse would acquire land from ten different landowners. The convicted murderer turned aviation entrepreneur appeared to be on a roll, but his ambitions would collide with yet another boondoggle.

In January 1932, Woodhouse entered into a contract with George W. Tolk, who was supposed to build and operate the Historic Celebrations Park. It was an attraction on the Air Junction grounds that would feature a replica of a schoolhouse that George Washington supposedly attended, and a Washington memorabilia museum. As Director of the Historic Celebrations Park, Tolk would also host ceremonies commemorating Washington’s 200th birthday on February 22. While Tolk built the replica schoolhouse, he neglected to build the rest of the park, and refused to host the bicentennial celebrations. Additionally, Woodhouse ran into problems with Albert H. Harrison, the landowner from whom he bought the land where the Historic Celebrations Park was to be built. Harrison failed to vacate the land and was blamed alongside Tolk for the uneventful passing of Washington’s bicentennial.

As it turned out, the birthday snafu was just the beginning of Woodhouse’s problems. He ran into financial difficulties building airport infrastructure, increasing his land holdings, and paying his trustees. He remortgaged several of his properties but couldn’t pay his bills. Starting in 1933, Woodhouse began to lose tracts of land in lawsuits filed against him by disgruntled lenders. Albert H. Harrison won a lawsuit over unpaid debts against Woodhouse and got his land back. Woodhouse appealed the Court’s decision in May 1937 to no avail. In desperation, he proposed to Congress to buy or lease the Air Junction and restore it as a national asset. The proposal came at a bad time. The Hindenburg disaster had occurred less than three weeks earlier. The multiple blows of lawsuits, the depressed economy, and the loss of interest in dirigibles was more than Woodhouse could bear. He sold all the Air Junction land by the end of 1937.9 Little more than runways had been built. It is unlikely that any aircraft ever landed or took off from the Air Junction.10

The last notable event in Woodhouse’s life was a 1953-58 lawsuit filed by an employee who worked in one of his New York art galleries. She claimed that she worked without pay, and Woodhouse retorted that she was only upset because he refused her access to important clients and wanted to offer her services as a fortune teller, which was illegal in New York. This bizarre episode would end in victory for the employee, and the loss of Woodhouse’s last remaining tracts of Virginia land, which had sat unused near the site of the Air Junction. When Henry Woodhouse died on January 6, 1970, in his New York home, he left no family, and over 35 personal damage lawsuits against real or imagined threats.11

While the story of Henry Woodhouse and the George Washington Air Junction came to an unremarkable end, the colorful history of Huntley Meadows would continue. The land that is now Huntley Meadows was acquired by the federal government in the 1940s, and over the next two decades, became a base for the aforementioned Cold War research and military defenses. In the 1960s, Fairfax County’s population was expanding, and the land started to be used by locals for recreation.

A 1971 agreement between the Navy and Fairfax County Park Authority designated 400 acres of the property for recreation. Beaver dams and the Potomac River’s oxbows (U-shaped bends) created Huntley Meadows’ wetlands during the 1970s and 80s. Ideas for a nature center, boardwalks and an equestrian center were drawn up. Early park advocate and volunteer Norma Hoffman fought to preserve the wetlands amid proposed developments.

A visitor’s center, nature trails, boardwalk and observation tower were completed in the 1980s. An 1825 villa built for George Mason’s grandson was brought under the protection of park ownership, with a restoration eventually beginning in 2010. Now called Historic Huntley, this landmark finally opened to the public in 2012.

The 1990s saw a total of 100,000 visitors coming to Huntley Meadows annually, but there was a decline in the resident and migratory bird population, hence the need for a massive wetlands restoration project. This effort expanded beyond just preserving remaining habitat. Facilities were renovated and environmental awareness and education programs were implemented. This ambitious project would finally be completed in 2013, bringing Huntley Meadows into the era of ecological prosperity and environmental consciousness that it enjoys today.12

Huntley Meadows continues to shelter a rich diversity of animal and plant life, and hosts thousands of visitors each year who seek their own refuge of peace and tranquility in one of the nation’s largest metro areas. Henry Woodhouse and the George Washington Air Junction appear to have been all but forgotten, but Huntley Meadows has become one of the region’s priceless natural treasures.

Footnotes

- 1

www.fairfaxcounty.gov. “Huntley Meadows Park History.” Government. Accessed September 27, 2023.

- 2

Reynolds, Clark G. “HENRY WOODHOUSE--WRITER, SELF-PROMOTER, CON MAN.” Accessed October 5, 2023.

- 3

Woodhouse, Henry. “Aero Club of America Bulletin,” April 10, 1912. The Ida M. Tarbell Collection, 1890-1944.

- 4

Kuntz, Jerry. “‘I’m Working on a Million Dollar Deal’: A Biographical Essay on Henry Woodhouse,” October 25, 2005.

- 5

“FOUND IN THE ARCHIVES, No. 55 - September 2019 Henry Woodhouse Fairfax Circuit Court Historic Records Center.” Fairfax Circuit Court Historic Records Center, September 2019.

- 6

“FOUND IN THE ARCHIVES, No. 55 - September 2019 Henry Woodhouse Fairfax Circuit Court Historic Records Center.” Fairfax Circuit Court Historic Records Center, September 2019.

- 7The Washington Post. “AIR JUNCTION SITE FORMALLY OPENED: Dedication of Field Named for George Washington Attracts Notables. IS ON ROAD TO RICHMOND.” February 23, 1929. ProQuest.

- 8

Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority. “History of Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport.” Archive, January 5, 2011.

- 9

“FOUND IN THE ARCHIVES, No. 55 - September 2019 Henry Woodhouse Fairfax Circuit Court Historic Records Center.” Fairfax Circuit Court Historic Records Center, September 2019.

- 10

Freeman, Paul. “Abandoned & Little-Known Airfields: Virginia: Southeastern Fairfax County.” Accessed October 1, 2023.

- 11

Kuntz, Jerry. “‘I’m Working on a Million Dollar Deal’: A Biographical Essay on Henry Woodhouse,” October 25, 2005.

- 12

www.fairfaxcounty.gov. “Huntley Meadows Park History.” Government. Accessed September 27, 2023.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)