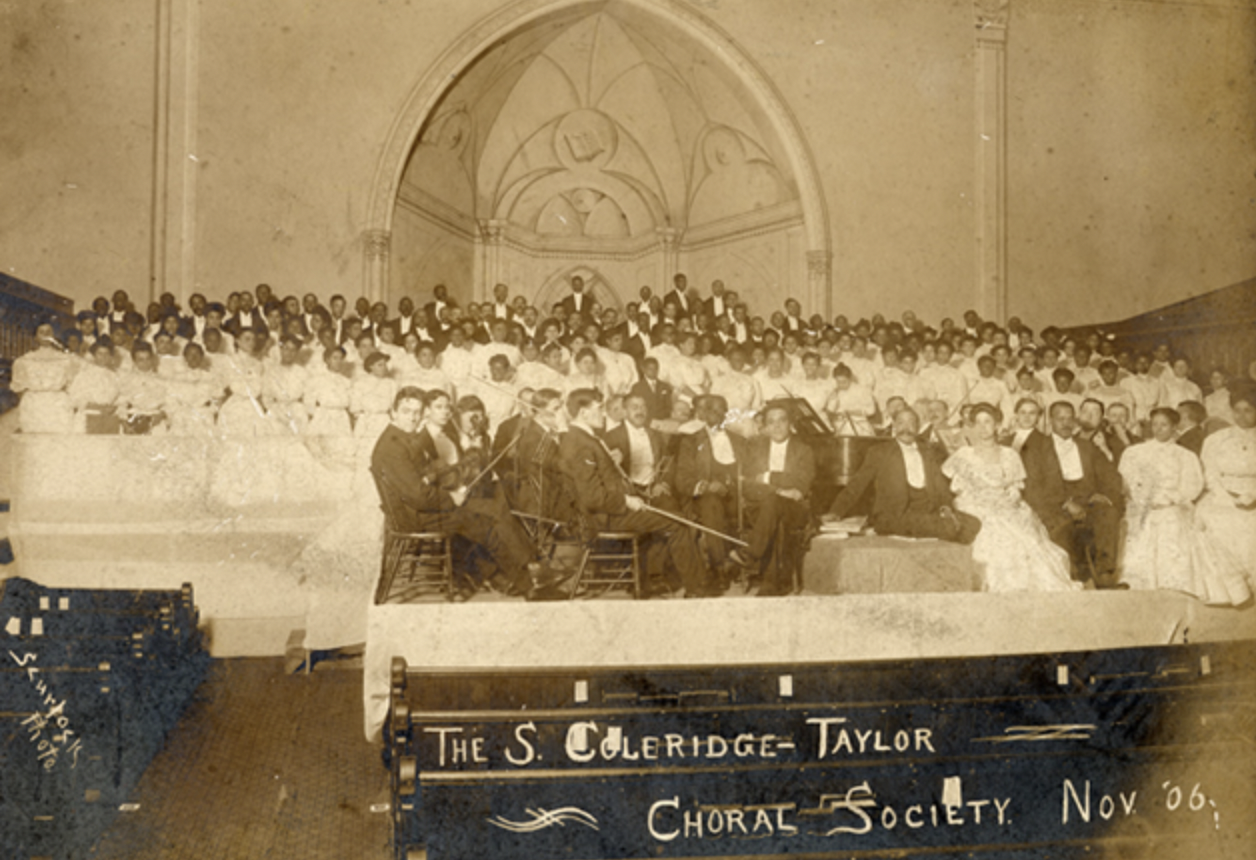

"It is Well for Us, O Brother": the Samuel Coleridge-Taylor Choral Society of Washington D.C.

By the end of the 19th century, Mamie Hilyer had secured a place at the forefront of Washington, D.C.’s cultural scene. A pianist and active member of the city’s Black upper class, she founded the Treble Clef Club -- a choral society consisting of herself and about twenty-five other women -- in 1897. The Treble Clef Club gave annual concerts and was devoted to the study of classical music – particularly that of Black composers. Thanks to Hilyer’s promotion efforts, the society was well respected both locally and nationally.1 Before long, however, Hilyer had set her sights overseas. A new and immensely popular composer from England named Samuel Coleridge-Taylor had caught her attention.

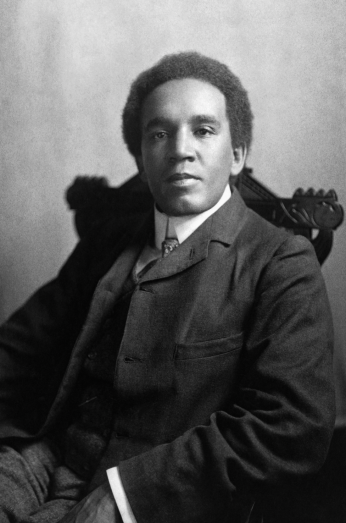

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor was a prolific composer, conductor, and violinist of British and Sierra Leonean descent. While studying at the Royal College of Music under Charles Villiers Stanford, he premiered his cantata “Hiawatha’s Wedding Feast,” the first of three that would make up his series The Song of Hiawatha. Having already gained notoriety for his Ballade in A Minor, many important musical figures were in the audience.2 The premiere was a success, later referred to as “one of the most remarkable events in modern English musical history.”3 This expedited Coleridge-Taylor to national, and eventually international, stardom. He would hold several professorships and conduct several important musical ensembles during his lifetime, including the prestigious Handel Choral Society of London.

In 1900, Hilyer traveled to England and arranged to meet Coleridge-Taylor at his home in Croydon. He impressed her immediately.

“The simple and unaffected manner, the ease and modesty of bearing, the enthusiasm and magnetic personality of this remarkable man, his intense interest in his people in the United States, his high musical standing in England…were qualities calculated not only to awaken our admiration, but unconsciously planted within us those seeds of inspiration, possibility and hope which were destined to grow in virgin soil and to blossom so abundantly.”4

Hilyer left her meeting with Coleridge-Taylor determined to bring the composer to the United States to conduct a festival of his works. She shared her enthusiasm with Lola Johnson, another Treble Clef Club member. Johnson then wrote the composer, who replied with a message of support and interest.

In 1901, Hilyer hosted a cadre of Washington’s Black musicians and educators at her home to anticipate what it would take to bring Coleridge-Taylor to D.C.5 This meeting became the inception of the Samuel Coleridge-Taylor Choral Society – which would consist of entirely Black musicians in an effort sustained and led by members of the African American community.

In the span of a year and a half, the choir remained together to learn and rehearse The Song of Hiawatha.6 Under the leadership of conductor John T. Layton, a music teacher in the city’s public schools, the choir was diligently drilled. The Washington Bee observed that Layton “demanded strict attention to the work in hand, and obtained it without being unnecessarily severe.” The choir maintained an immensely supportive atmosphere; they applauded one soloist so long that Layton had to interrupt by saying, “please reserve a little of your enthusiasm for your own work.”7

By January 1903, it was announced that the Samuel Coleridge-Taylor Choral Society would be performing Hiawatha for the first time in April of that year.8 Although the Society planned for the composition be performed with an orchestra, ensembles of both local White and Black amateur musicians had to be dismissed prior to the concert due to the difficulty of the composition.9 Instead, Layton and the other organizers made the decision that the regular accompanist for the choir, Mary Europe, as well as Gabriella Pelham and William Braxton, would instead accompany the choir on pianos and organ.

On April 23rd, 1903, a racially mixed audience of over 2,000 witnessed the Samuel Coleridge-Taylor Choral Society’s first performance of Hiawatha at the Washington African Methodist Episcopal Church. Headlining the performance were three visiting soloists who were among the most accomplished Black performers in the United States – Kathryn Skeene-Mitchell, Sidney Woodward, and Harry Burleigh -- a vocalist, composer, and a student of Antonin Dvořák who introduced him to the African-American spirituals he used in his New World Symphony. Having been advertised for weeks, the performance was sold out and people had to be turned away at the door.

Both African American and White newspapers gave the choir’s performance glowing reviews, though in the New York Times much of it was wrapped in racism endemic of Jim Crow: “Those who came expecting to make allowances for inadequate singing because it was by colored people went away wondering whether so effective a chorus had ever been heard in Washington.”10

Special praise was given to the choir’s bass section, which, according to the Evening Star, “like the harmony of some splendid organ…formed the substantial basis on which the concerted work rested.”11

The press also praised the accompanying musicians extensively. Writing for Colored American, Walter Hayson exclaimed that Mary Europe “played the score of ‘Hiawatha’ so exacting in its readings, rhythm, time and tempo, with such precision, power and intelligence that she received the most cordial thanks of the soloist and almost extravagant commendation of the musical critics.”12

Following the success of the first performance, Mamie Hilyer’s husband, Andrew, contacted Samuel Coleridge-Taylor to arrange a date in which he might come to the United States and conduct his namesake Choral Society. After reading newspaper reviews of the April 1903 concert the composer required little convincing. In a letter to Hilyer he wrote, “I don’t think anything else would have induced me to visit America, excepting the fact of an established society of coloured singers; it is for that, first and foremost, that I am coming, and all other engagements are secondary.”13

Unfortunately, prior teaching engagements in England kept the composer from traveling until the end of 1904 but it was decided that Coleridge-Taylor would conduct two concerts in Washington. The first would consist of a performance of his Hiawatha trilogy on November 16th, 1904, with a second performance of his recent and popular works on the next day. This program would feature two of his Choral Ballades, which were dedicated to the society, the Hiawatha overture, and the recently published Four African Dances for violin and piano.

The anticipation of Coleridge-Taylor’s arrival led to preparations on an even larger scale. The Washington Convention Hall, which could seat an audience of 2,700 and accommodate 400 more standing, was reserved, and the U.S. Marine Band was enlisted to provide orchestration.14 The concert was advertised in both the city’s Black and White newspapers, and the Evening Star conducted an interview with Coleridge-Taylor to garner interest. Once again, the society enlisted excellent and reputable Black soloists – Estelle Pinckney Clough from Massachusetts, J. Arthur Freeman from St. Louis, and Harry Burleigh returning for his second performance with the choir.15

As the concert approached, Washington was abuzz. The Washington Post posited in April 1904 – six months before his visit, “if you were to ask the first comer you meet in the street whether he knew ‘Hiawatha’ he would immediately be ready to whistle it.”16 Several important members of the government were slated to attend, including the Secretary of the recently re-elected President Roosevelt.17 No tickets were available at the door.

The audience would not be disappointed. Once more, the performance of the choir was praised extensively. As the Evening Star gushed, “The chorus of two hundred responded almost instinctively to very move of the conductor’s baton.”18

However, this praise did not extend to the orchestra. The Washington Post commented that the Marine Band’s performance was “at times inexcusably bad, playing out of tune many times being very ragged and amateurish."19 Coleridge-Taylor agreed, later writing to Andrew Hilyer that the orchestra had one-tenth the quality of the singers. The composer’s biographer Jeffrey Green theorized that, “either the music may have been difficult, or the instrumentalists did not bother themselves for a black conductor and a largely black audience.”20

During his visit to Washington, Coleridge-Taylor’s other engagements included a meeting with President Roosevelt, from whom he received a signed photograph. The members of the Choral Society also gave him a silver loving-cup inscribed with lines from “Hiawatha’s Departure”: “It is well for us, O brother, That you come so far to see us.”21

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor’s visit to America meant much more than two thrilling nights of music. As Andrew Hilyer wrote to the composer afterward:

“In composing Hiawatha you have done the coloured people of the USA a service which, I am sure, you never dreamed of when composing it. It acts as a source of inspiration for us, not only musically but in other lines of endeavour.”

It is not an exaggeration to say that the Coleridge-Taylor Choral Society helped shape the musical trajectory of Washington D.C. in the first half of the 20th Century. The composer and his namesake Society successfully raised the profile of Black musicians and performers at a time when Jim Crow sought to strike down Black advancement.

As W.E.B. Dubois wrote in Darkwater, “born here, [Coleridge-Taylor’s ability] might never have been permitted to grow. We know in America how to discourage, choke, and murder ability when it so far forgets itself as to choose a dark skin.”22

The performances of the Coleridge-Taylor Society also sparked a conversation among members of the White press about the role of Black people in historically White musical circles. As the New York Times remarked after the Choral Society’s first performance in 1903, “the concert opens up a field of interesting speculation as to the possibility of the colored people in the higher regions of music…”23

The idea that African Americans deserved recognition and a place in the highest echelon of music was, of course, nothing new to Mamie Hilyer. It was, in many ways, her life’s work. As woman’s rights activist Coralie Franklin Cook remarked, Hilyer “aroused an inspiration among the musical people of this city that caught and kindled until it blazed forth in the triumphant culmination which has won the unstinted praise of musical critics of all classes.”24

Footnotes

- 1 Doris Evans McGinty, “As Large as She Can Make It: The Role of Black Women Activists in Music, 1880-1945,” in Cultivating Music in America: Women Patrons and Activists Since 1860, ed. Ralph P. Locke and Cynthia Barr (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997), 217.

- 2 Ellsworth Janifer, “Samuel Coleridge-Taylor in Washington,” in Phylon 28, no. 2 (1967): 186-7. The Ballade in A Minor was commissioned on recommendation of Sir Edward Elgar, who was considered England’s foremost composer of the time.

- 3 “Samuel Coleridge-Taylor. Born August 15, 1875. Died September 1, 1912,” in The Musical Times 53, no. 836 (1912): 638.

- 4 Avril Coleridge-Taylor, The Heritage of Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, Student’s Music Library (London: D. Dobson, 1979), 50.

- 5

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, S. Coleridge-Taylor Choral Society, and Daniel Murray Pamphlet Collection, Scenes from The Song of Hiawatha(Washington, D.C.: 1904).

- 6 “The S. Coleridge Taylor Choral Society,” in Colored American, April 11, 1903, America’s Historical Newspapers.

- 7 “Negroes and Music,” Washington Bee, January 9, 1904, America’s Historical Newspapers.

- 8 “S. Coleridge-Taylor Choral Society.”

- 9 Jeffrey P. Green, Samuel Coleridge-Taylor: A Musical Life (London: Pickering & Chatto, 2011), 128.

- 10 Special Correspondence, “A Negro’s Music.”

- 11 “An Excellent Performance: S. Coleridge Taylor’s ‘Hiawatha’ Given Last Night,” in Evening Star, April 24, 1903, America’s Historical Newspapers.

- 12 Walter Hayson, “The Hiawatha Concert. The Highest Expression of Musical Culture,” in Colored American, May 2, 1903, America’s Historical Newspapers.

- 13 William Charles Berwick Sayers and J. H. Smither Jackson. Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, Musician: His Life and Letters(London : Cassell, 1915), 154.

- 14 “‘Hiawatha’ To-Night: S. Coleridge-Taylor’s Masterpiece to Be Sung at Convention Hall,” The Washington Post, November 16, 1904.

- 15 Green, Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, 132.

- 16 A. Kaufmann, “Hiawatha a Classic: Great Work of the Famous Negro Composer -- Sketch of Coleridge Taylor -- Regarded as England’s Greatest Contemporary Musician -- His Treatment of Longfellow’s Poem a Work of Inspirational Power -- To Be Sung in Washington by the Coleridge-Taylor Society,” in The Washington Post, April 10, 1904.

- 17 Green, Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, 132.

- 18 Presents ‘Hiawatha,’” Evening Star, November 17, 1904.

- 19 “Under Composer’s Baton: "Hiawatha" Rendered by the Coleridge- Taylor Choral Society,” The Washington Post, November 17, 1904. According to the historians of the Marine Band, this review from the Post may have been biased against the Marine Band. In an article titled “War on Marine Band” from May 1904, the Post reported that members of the Marine Band were taking the place of theater orchestra musicians while they were on strike, causing President Roosevelt to intervene. See “War on Marine Band: Musicians’ Federation Considering Its Status – The President Takes a Hand -- He Directs That an Order Be Issued Prohibiting Any Member of Marine Band from Filling the Place of a Civilian Musician on Strike or Locked Out -- Theater Orchestra Affected,” The Washington Post, May 17, 1904.

- 20 Green, Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, 132.

- 21 Coleridge-Taylor, The Heritage of Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, 56.

- 22 W.E.B. DuBois, “The Immortal Child,” in Darkwater: Voices from Within the Veil, (New York: Harcourt, 1920), 199.

- 23 Special Correspondence, “A Negro’s Music.”

- 24 “Its Work Commended: Meeting of Coleridge-Taylor Choral Society,” Evening Star, April 29, 1903. Access World News – Historical and Current.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)