The DMV's Worst Natural Disaster: The Chesapeake Bay Asteroid

The Chesapeake Bay is remarkable for its beauty and regional culture. The nation’s largest estuary sustains a region that encompasses six states and is home to more than 18 million people. Yet underneath the weekend sailors, glassy waters and quaint beachside townhomes lies a dark history that has become invisible to the bay’s residents and tourists.1 No, its population isn’t hiding some nefarious secret. It’s more like Earth itself is hiding something: a cosmic disaster so intense that if the same event happened today, the DMV would literally be wiped off the face of the earth.

The first clue to this hidden disaster was discovered not in the Chesapeake Bay, but 93 miles off the coast of Atlantic City, New Jersey. It was 1983, the final year of the Deep Sea Drilling Project (DSDP), an ocean drilling program coordinated by the Scripps Institute of Oceanography that had been running since 1968. The overarching purpose of the DSDP was scientific exploration, with the goal of collecting sediment samples from the ocean floor to develop the scientific community’s understanding of plate tectonics and the ocean’s geology.2 In July 1983, scientists aboard a ship off the New Jersey coast found something unusual in a sediment core brought up from the seabed. Inside the core was a 10-centimeter-thick layer of molten glass particles that could only have been created under intense heat and energy. The glass particles are called tektites, which are often part of debris from an asteroid impact, called ejecta.3

Mixed with the ejecta were microscopic fossils of tiny marine animals and plants. Studies of microfossils and argon isotopes revealed that this ejecta layer matched similar layers discovered in the Caribbean Sea and the Gulf of Mexico, all rich with tektites and microfossils. The ejecta layers were determined to be 35 million years old. The abundance of tektites and the identical ages revealed that these layers all originated from a single asteroid impact that sent a blanket of ejecta raining down over North America, hundreds of miles in every direction from the site of the impact. But even with the discovery of this enormous radius of debris, called a tektite field, one big mystery remained.4 Where exactly did the asteroid hit?

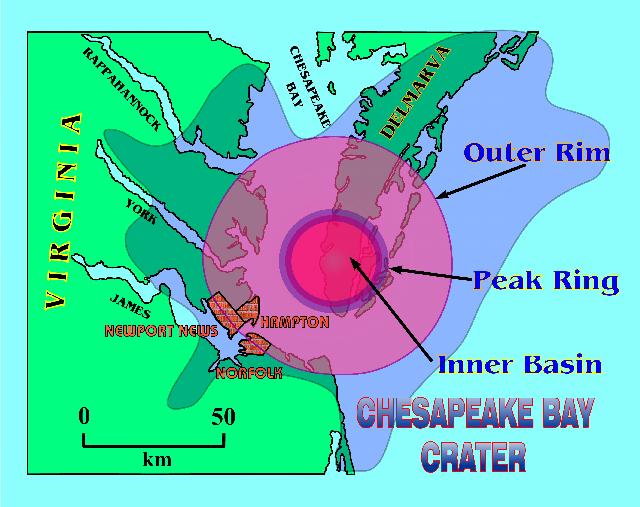

Geologists had long suspected that some pivotal event affected the strange geology of the Chesapeake Bay region. Virginia is pockmarked by salty groundwater aquifers, which have been known since at least the American Civil War. This is unusual, as is how the James, York and Rappahanock rivers bend at sudden angles near the coast, when normal East Coast rivers gently incline towards the Atlantic.5 Up until about 30 years ago no one knew the cause(s) of these geological anomalies. But in 1989, seismic survey trucks searching for petroleum and natural gas for Texaco pumped soundwaves into the ground at Cape Charles, Virginia, right at the tip of the Calvert Peninsula, where the Chesapeake Bay meets the Atlantic. The trucks captured the reflections of the soundwaves, hoping to spot signs of oil and gas that lay underneath Chesapeake Bay. As it turned out, Texaco didn’t find their lucrative fossil fuels,6 but they did find something else quite strange.

Dr. David Powars of the United States Geological Survey (USGS) long suspected the Chesapeake Bay was hiding some ancient secret. The aquifers, bendy rivers and tektite-laden cores all pointed to a common cause, but Powars needed more data. Powars was collecting sediment cores at the Chesapeake Bay when his colleague saw the seismic survey trucks and asked what they were doing. The drivers told him, and it then took Powars four years to get his hands on the surveys. Texaco was very reluctant to reveal its surveys because of fear of competitors. In 1993, Powars finally got his hands on the Texoco records and saw the reflections. It was clear that a massive bowl of ancient rubble sat under Chesapeake Bay.

Powars consulted Dr. C. Wylie Poag of the USGS, who was studying another undersea impact crater further up the east coast at the time. Poag confirmed Powars’ theory of an asteroid impact crater underneath the Chesapeake Bay. Poag, Powars and the colleague who waved down the survey trucks announced their discovery in a 1994 article in the scientific journal Geology. The announcement article faced skepticism, but Poag later collected cores from the Chesapeake crater that found abundant tektites, convincing even the skeptics of the Chesapeake Bay impact crater’s existence.7 Dr. Poag has become one of the world’s foremost experts on the crater, continuing his research through the 1990s and writing The Chesapeake Invader (1999), a book chronicling the impact and its discovery.8

The mystery was solved. All of the geological anomalies of the Chesapeake Bay were caused by how sediment was deposited in the seconds and 35 million years after a giant asteroid carved out a huge chunk of the landscape.9 But discovering this event through data does little to illustrate what it must have been like to be near ground zero on that fateful day 35 million years ago.

It was a time of Earth’s history called the Eocene epoch. Ironically, the dinosaurs had already been killed by another asteroid, leaving mammals as the dominant animals on the planet. Increased levels of CO2 led to tropical global temperatures, which facilitated the growth of rainforests around the world. Earth was a jungle world straight out of James Cameron’s Avatar. A greenhouse Earth also meant there was less ice at the poles, and so the oceans were much higher than today. D.C. would have been mostly underwater, with ridges (like where the National Cathedral is today) forming an island archipelago. The Atlantic coast was somewhere near Richmond, Virginia.

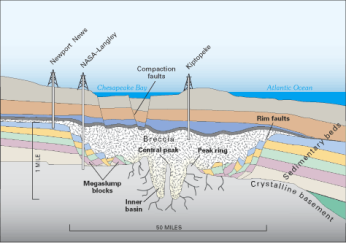

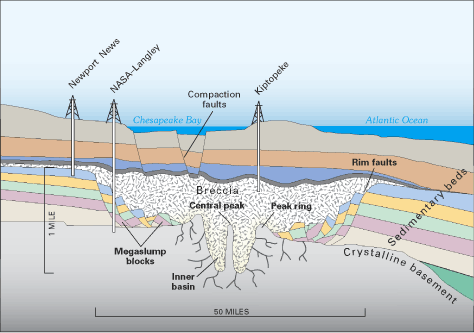

On Chesapeake Asteroid Day all those years ago, if you were standing in what is now D.C., you may have seen a blinding flash of light arcing across the sky from the northwest. At a speed of 11 miles per second, the two- to five-mile-wide asteroid struck 200 miles away at Cape Charles, which was underwater back then.10 The asteroid burst through 600 to 1,500 feet of ocean before penetrating five miles into the seafloor. It was as if Earth got shot with a bullet. Fractures were driven as deep as seven miles. Judging by other similar impacts, rock in the crater could have superheated to 4,000 degrees Fahrenheit, hotter than lava. To be fair, the asteroid didn’t fare any better than the earth. It was instantly vaporized into gas by the heat and energy of the impact. As water and sediment rushed back into the crater, the edge expanded beyond the 17-mile-wide hole carved by the asteroid, widening the crater to 25 miles.11

The energy from the blast would have been like all of the world’s nuclear arsenal going off at once, multiplied by hundreds of thousands of times. An infrared wave ignited all the forests within at least a hundred miles. D.C. would have been instantly set ablaze. You would have been incinerated before you could even process what was happening. Hurricane-force winds whipped up firestorms across Virginia’s Piedmont region. A shockwave spread out like ripples after throwing a rock into water. Every tree was flattened, every animal that didn’t get barbecued was blasted as if struck by a jetliner.12 Millions of tons of rock and molten glass were cast high into the atmosphere in a mushroom cloud that reached 15 to 30 miles into the sky, and extended hundreds of miles out in every direction. Some of this ejecta crashed back down all over the East Coast. Chunks of rubble as big as buildings or ships could have set off their own meteor impacts, creating secondary craters and areas of destruction. In total, the tektite field was four million square miles in diameter, with ejecta raining down as far away as Texas and Barbados. As if all that wasn’t enough, the impact created a megatsunami that could have been 1,500 feet tall, and reached all the way to the Blue Ridge Mountains 450 miles away. Any living thing not roasted, flattened or crushed would have been literally wiped off the face of the earth. All of this destruction happened within just fifteen minutes.13

Today, the crater from the asteroid that caused all that destruction sits at the bottom of the Chesapeake Bay. (Which, incidentally, didn’t exist at the time -- it formed between 18,000 and 10,000 years ago when melting glaciers raised sea levels that flooded the Susquehanna Valley.) Although the direct point of impact is smaller, the entire crater is 53 miles wide in diameter, twice the size of Rhode Island, and 0.81 miles deep, almost as deep as the Grand Canyon. The 17.6-mile wide Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel that connects Cape Charles to Virginia Beach crosses part of it.

Our planet has been bombarded by asteroids, comets and meteors since its beginning, but even among countless impacts, the Chesapeake Bay event stands out. It created the largest impact crater in the United States, and the sixth largest in the world.14 Today, Cape Charles memorializes the impact with a sign on a fishing pier and an exhibit at the Cape Charles Museum and Welcome Center.15 It was featured in Mary Robinette Kowal’s The Calculating Stars, a novel that imagines the impact happening in the 1950s, causing a climate crisis that forces humanity to search for a new home among the stars.16

Americans can count our blessings that the impact missed us by 35 million years, but once in a blue moon there are events that remind humanity of our fragile place in the universe. The Chelyabinsk meteor that exploded over Siberia in 2013 was only 59 feet wide and never touched the ground, but still injured almost 1,500 people and damaged 7,200 buildings.17 With the possible threat of space rocks always hanging over our heads (literally), perhaps it’s time that Chesapeake Bay residents claim an apocalyptic asteroid impact as part of their region’s history. Maybe it can teach us that we can never take our eyes off the skies, and give us hope that as bad as we think current times might be, at least we aren’t living in 35,000,000 B.C..

Footnotes

- 1

Chesapeake Bay. “What Is a Watershed?” Accessed December 7, 2023.

- 2

Palmer, Amanda A. “Explanatory Notes, Deep Sea Drilling Project Leg 95, New Jersey Transect.” Ocean Drilling Program, November 28, 2023.

- 3

Poag, C. Wylie. “Coring the Chesapeake Bay Impact Crater.” Geotimes 49, no. 1 (2004): 22–25.

- 4

Specktor, Brandon. “America’s Largest Asteroid Impact Left a Trail of Destruction Across the Eastern United States.” Livescience.Com, August 15, 2019.

- 5

United States Geological Survey. “The Chesapeake Bay Bolide Impact: A New View of Coastal Plain Evolution - USGS Fact Sheet 049-98.” Government. Accessed December 7, 2023.

- 6

Chesapeake Bay Foundation. “Offshore Drilling,” 2018.

- 7

Tennant, Diane. “THE CHESAPEAKE BAY METEOR: A Mystery, Meterors and One Man’s Quest for the Truth.” CBGS Environmental Science, June 24, 2001.

- 8

Wylie Poag, C. Chesapeake Invader: Discovering America’s Giant Meteorite Crater, 2017.

- 9

United States Geological Survey. “The Chesapeake Bay Bolide Impact: A New View of Coastal Plain Evolution - USGS Fact Sheet 049-98.” Government. Accessed December 7, 2023.

- 10

Prehistoric. Episodic, Documentary. Discovery Channel, 2009.

- 11

Wünnemann, K., and R. Weiss. “The Meteorite Impact-Induced Tsunami Hazard.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 373, no. 2053 (October 28, 2015): 20140381.

- 12

Prehistoric. Episodic, Documentary. Discovery Channel, 2009.

- 13

Wünnemann, K., and R. Weiss. “The Meteorite Impact-Induced Tsunami Hazard.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 373, no. 2053 (October 28, 2015): 20140381.

- 14

Powars, David. Chesapeake Bay Impact Crater | U.S. Geological Survey. Lecture, 2013.

- 15

Northampton County, Virginia. “Chesapeake Bay Impact Crater.” Government. Accessed December 7, 2023.

- 16

Robinette Kowal, Mary. The Calculating Stars. The Lady Astronaut. MacMillan, 2023.

- 17

published, Nola Taylor Tillman. “Effects of Ancient Meteor Impacts Still Visible on Earth Today.” Space.com, September 23, 2013.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)