Celebrating 25 Years of the Rainbow History Project

This June, people from all over the world gathered in Washington, D.C. to celebrate LGBTQIA+ Pride Month. This year, though, the annual event was even bigger, as the capital city hosted World Pride events—a nod to the fiftieth anniversary of D.C.’s Pride celebrations.1 While celebrations last all month long, the grand parade made its way through D.C. streets on June 7.

It may seem like a given that such a large event would be documented, since photos from the parade alone dominated camera rolls and social media newsfeeds that weekend. Media from all over the world wrote about the event. Visitors to D.C. can purchase commemorative merchandise: art, posters, clothing, flags, and more. Everything is kept and preserved, either in the digital world or in the depths of dresser drawers. But for D.C.’s LQBTQIA+ community, their historic events weren’t always so well-covered—or well-preserved.

D.C. is lucky to have access to so many public archives and repositories, from major institutions like the Library of Congress, Smithsonian, and National Archives to local organizations like the DC History Center and the public library. These places hold records, photographs, objects, and other materials that tell our community’s story. When historians and writers (including those at Boundary Stones) sit down to tell the story of D.C., they rely on the things stored within these collections. However, for much of history, these collections did not always reflect the full story—in many cases, materials relating to marginalized groups were not deemed worthy of official protection or preservation. What happens when you want to tell a story, but don’t have any access to what you need to tell that story?

It's a problem that occurred to D.C. resident Mark Meinke back in 2000. A member of the District’s large and vibrant LGBTQIA+ community, he was working on a book about drag performers when he ran into a huge roadblock: there were no archives covering the history of his research subject or his community as a whole. “D.C., unlike other Gay centers, has no available and accessible community memory or archives,” he wrote later.2 The public library did give him access to all published issues of the Washington Blade, a LGBTQIA+ newspaper founded in 1969 which covered many of the shows and events Meinke wanted to write about. But as for everything else—photos, memoirs, objects, all the things that most groups expect to find in repositories—Meinke was coming up short.3

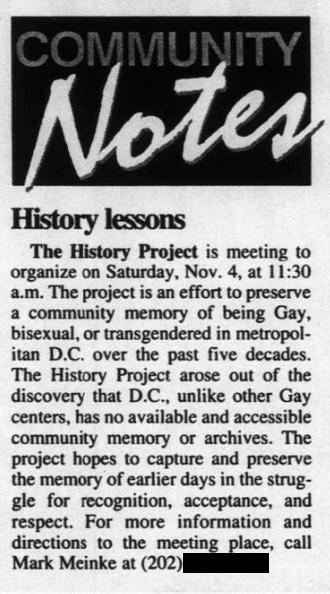

Frustrated but now inspired, Meinke decided to take action. In the fall of 2000, he established a new action group he called “the History Project,” which he hoped would “capture and preserve the earlier days in the struggle for recognition, acceptance, and respect.”4 Knowing he couldn’t carry out the mission alone, he placed an advertisement in the November 3, 2000 issue of the Blade, calling for any interested volunteers.

The next day, November 4, Meinke made his way to the CyberStop Café on 17th Street NW, the designated meeting place for his new project. In an interview to mark the project’s twentieth anniversary, Meinke admitted he was terrified that he’d be alone at the café table, but eventually a founding group assembled: Meinke, Charles Rose, Bruce Pennington, Jose Gutierrez, and James Crutchfield.5 All of them agreed that, if they wanted to honor and preserve their community’s stories, they had to act fast. They met again the following weekend, placing another Blade advertisement that made their goals quite clear: anyone interested in the project, anyone who knew potential interview subjects or wanted to conduct interviews, and anyone with relevant personal connections should meet at the CyberStop Café.6

In their early days, “the History Project” prioritized the creation and collection of oral histories—interviews with community leaders, activists, and other witnesses to history. Time and natural causes—the AIDS epidemic in particular—had taken its toll, so project members knew they needed to capture memories while they were still available. Meinke remembered taking a tape recorder with him wherever he went, even missing a movie showtime because he began to interview the people standing with him in the box office line.7 Gradually, with every interview, the new archive expanded. The Project also began collecting documents, material objects, and photos from community members who, thankfully, saved these things in their own private collections. As the movement became bigger, they gave themselves an official name that has stuck: the Rainbow History Project.

Since November 2000, volunteers for the Rainbow History Project have collected materials invaluable to D.C.’s LGBTQIA+ community, also launching community-wide projects to safeguard their history. In addition to those interviews and oral histories, there have been efforts to document and list historic sites in the District; organize public exhibitions; preserve the impact of worldwide events hosted in D.C., like the AIDS Memorial Quilt; and host lectures and other events. In a 2024 interview with WTOP, Vincent Slatt, the Rainbow History Project’s Director of Archiving, said that their collections have grown to “approximately a quarter of a million pages of documentation,” and counting.8 In 2008, the DC History Center announced that they would house the Rainbow History Project’s collections—a full-circle moment for Meinke and the Project’s founders, who wanted their materials available in public repositories in the District. Thanks to their efforts, anyone researching LGBTQIA+ history in D.C. has a wealth of information at their fingertips, also digitized and available in databases online.

To celebrate World Pride in D.C., the Rainbow History Project coordinated their largest exhibit to date: “Pickets, Protests, and Parades: The History of Gay Pride in Washington,” telling the long and rich history of the Pride movement in D.C.9 The free outdoor exhibit, installed in Freedom Plaza on Pennsylvania Avenue NW, can be viewed through July 6, 2025. It’s a testament to the power of community activism, preservation, and storytelling.

Footnotes

- 1

World Pride: Washington, D.C., https://worldpridedc.org/

- 2

“History lessons,” The Washington Blade (Washington, D.C.), 3 November 2000, 65.

- 3

“Rainbow History Project 20th Anniversary Stream,” The DC Center on Facebook, 3 December 2020, https://www.facebook.com/thedccenter/videos/2764814427067904

- 4

“History lessons,” The Washington Blade (Washington, D.C.), 3 November 2000, 65.

- 5

“Rainbow History Project 20th Anniversary Stream.”

- 6

“Community memories,” The Washington Blade (Washington, D.C.), 10 November 2000, 71.

- 7

“Rainbow History Project 20th Anniversary Stream.”

- 8

Stephanie Gaines-Bryant, “DC’s Rainbow History Project reflects on 60 years of LGBTQ history ahead of World Pride,” WTOP, 10 June 2024, https://wtop.com/dc/2024/06/the-rainbow-history-project/

- 9

“Pickets, Protests, and Parades: The History of Gay Pride in Washington,” The Rainbow History Project, https://rainbowhistory.org/pride-exhibit/

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)