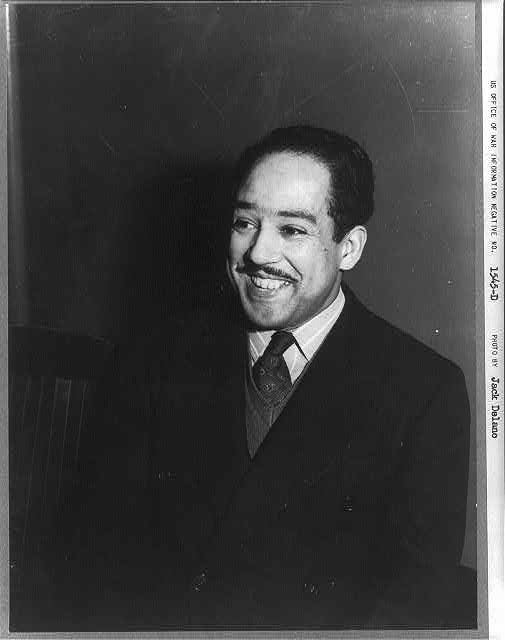

Langston Hughes: D.C.’s Original Busboy-Poet

One of D.C.’s most popular eateries is Busboys and Poets, a bookstore-café with locations all over the city. You could be forgiven for thinking the name is simply in reference to the kinds of people who might find themselves at a bookstore-café: busboys and poets. However, the name honors one busboy-poet in particular who has surprising ties to D.C.: Langston Hughes.

Hughes is best known as a poet of the Harlem Renaissance, with his legacy tied squarely to New York. But the origins of his literary career are in Washington. Born in Missouri in 1901, Hughes spent his childhood and adolescence moving around the midwestern United States. He picked up writing as a high school student and received recognition from his school for his writing. After high school, he began several years of international travel spanning Mexico, Africa, and Europe, working his way across the globe as a teacher, server, and sailor, among other odd jobs.1

In 1924, at the age of 22, he decided it was time to settle down, save up for college, and shop his poems around to publishers. He chose Washington, D.C. as his base because his mother and brother lived there. In Washington, he expected to find a respectable, literary job at the Library of Congress or a university library. However, he didn’t have the right qualifications and found D.C. to be more rigidly segregated than he had anticipated.2 He skipped from job to job, working first as a launderer, then an office assistant, before finally landing at the Wardman-Park Hotel on Connecticut Avenue as a busboy.3

On top of his struggle to find a fulfilling job, Hughes also struggled to fit into the city socially. He was used to living in relatively integrated cities in Europe and Mexico, and found D.C. segregated not only by race, but also by class within the city’s Black community. He deemed D.C.’s Black high society “snobbish.”4 He would later go on to criticize Washington’s snobbishness in his essay “Our Washington Society,” published in 1927 after he had left D.C.

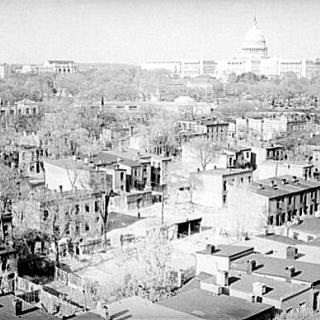

He felt most at home on Seventh Street, where he was inspired by the unpretentious creativity in the people he met. In his autobiography The Big Sea, he wrote,

From all this pretentiousness Seventh Street was a sweet relief. Seventh Street is the long, old, dirty street, where the ordinary Negroes hang out, folks with practically no family tree at all, folks who draw no color line between mulattoes and deep darkbrowns, folks who work hard for a living with their hands. On Seventh Street in 1924 they played the blues, ate watermelon, barbecue, and fish sandwiches, shot pool, told tall tales, looked at the dome of the Capitol and laughed out loud. I listened to their blues...

I tried to write poems like the songs they sang on Seventh Street—gay songs, because you had to be gay or die; sad songs, because you couldn’t help being sad sometimes. But gay or sad, you kept on living and you kept on going. Their songs— those of Seventh Street—had the pulse-beat of the people who keep on going. Like the waves of the sea coming one after another, always one after another, like the earth moving around the sun, night, day—night, day—night, day— forever, so is the undertow of black music with its rhythm that never betrays you, its strength like the beat of the human heart, its humor, and its rooted power.5

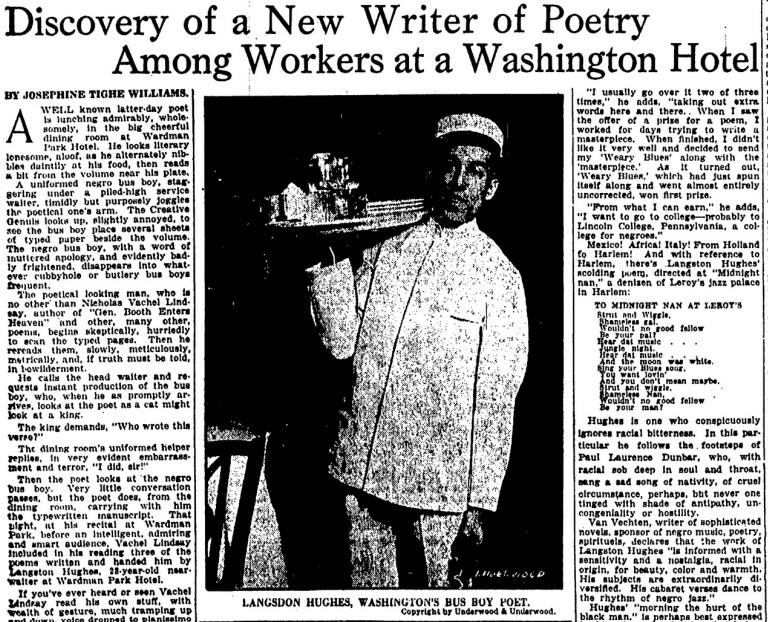

From this well of creative inspiration came one of Hughes’s first major literary successes, a poem called “The Weary Blues.” He submitted “The Weary Blues” to a poetry contest on a whim. He said in an interview with the Star, “When I saw the offer of a prize for a poem, I worked for days trying to write a masterpiece. When finished, I didn’t like it very well and decided to send my ‘weary blues’ along with the ‘masterpiece.’ As it turned out, ‘Weary Blues,’ which had just spun itself along and went almost entirely uncorrected, won first prize.”6

Hughes was already well on his way to literary acclaim, with this award under his belt plus published work in the Evening Star and The Crisis,7 when he was “discovered” by Washington’s literary elite. While Hughes was working as a busboy at the Wardman-Park Hotel, a celebrated white poet visited the hotel for a reading. This poet, whose fame has since been massively eclipsed by Hughes’s own, was Nicholas Vachel Lindsay. Lindsay shared Hughes’s midwestern roots and was known for his nostalgic poetry in which he often invoked race as a metaphor. He was criticized by Black writers and intellectuals of the time, like W.E.B. Du Bois, for his stereotypical and one-dimensional portrayals of Black characters.8

Though Lindsay’s depictions of race have complicated his legacy, his poetry was all the rage in 1925. When Hughes saw Lindsay dining in the Wardman-Park's restaurant, he saw an opportunity he couldn’t miss.

That afternoon I wrote out three of my poems, 'Jazzonia,' 'Negro Dancers,' and 'The Weary Blues,' on some pieces of paper and put them in the pocket of my white bus boy’s coat. In the evening when Mr. Lindsay came down to dinner, quickly I laid them beside his plate and went away, afraid to say anything to so famous a poet, except to tell him I liked his poems and that these were poems of mine. I looked back once and saw Mr. Lindsay reading the poems, as I picked up a tray of dirty dishes from a side table and started for the dumb-waiter.9

Lindsay took the time to read the poems, and he liked what he read. He liked them so much that he read out three of Hughes’s poems at his poetry reading that night. As Lindsay described it, the poems were, “Blues, sweet blues—coming from a black man’s soul.”10 He also called up the press to share the news of the bright young poet toiling at the hotel. Hughes recalled the aftermath of Lindsay’s visit:

The next morning on the way to work, as usual I bought a paper—and there I read that Vachel Lindsay had discovered a Negro bus boy poet! At the hotel the reporters were already waiting for me. They interviewed me. And they took my picture, holding up a tray of dirty dishes in the middle of the dining room. The picture, copyrighted by Underwood and Underwood, appeared in lots of newspapers throughout the country. It was my first publicity break.11

In the following days, Hughes was hounded by the press and would often be called out to the restaurant so that patrons could gaze upon the famed “Negro bus boy poet.” He was grateful for the career boost, but embarrassed by the attention and annoyed by how it interrupted his job. Not long after, he quit.12

Though he did not comment directly on the racial dynamics of his “discovery” by Lindsay, he went on to write extensively about the struggles of Black writers facing outsize expectations from both Black and white audiences. In his landmark essay, “The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain,” which he published in The National just a year after the Wardman-Park incident, he writes, “The Negro artist works against an undertow of sharp criticism and misunderstanding from his own group and unintentional bribes from the whites. 'O, be respectable, write about nice people, show how good we are,' say the Negroes. 'Be stereotyped, don’t go too far, don’t shatter our illusions about you, don’t amuse us too seriously. We will pay you,' say the whites.”13

This is the line he walked while embarking on his literary career in Washington. The Big Sea paints a picture of a young writer deeply dissatisfied with his life and with Washington as a city. However, Hughes wrote prolifically during his time in D.C., in part because he was so unhappy there. Years later he recalled, “I felt very bad in Washington that winter, so I wrote a great many poems. (I wrote only a few poems in Paris, because I had had such a good time there.) But in Washington I didn’t have a good time. I didn’t like my job, and I didn’t know what was going to happen to me, and I was cold and half-hungry, so I wrote a great many poems.”14

In The Big Sea he writes that his best memories of D.C. were of the poetry he wrote and the friends he made through writing. His award-winning poem, "The Weary Blues," would go on to become the basis for his first poetry collection, which was published in 1926 and drew inspiration from Hughes’s time in D.C. He spent only two years in Washington, before moving on to college at Lincoln University and a superstar literary career in New York.15

Despite his short-lived stint as a Washingtonian, Hughes is well remembered and much beloved in the city. Busboys and Poets was founded in 2005, with its name honoring Hughes. The name is especially apt because like Hughes, Busboys and Poets aligns itself with activism and the history of social justice.16 Today it remains a place where writers can find community and inspiration amid the hustle and bustle of D.C., just like Langston Hughes.

Footnotes

- 1 Williams, Josephine Tighe, “Discovery of a New Writer of Poetry Among Workers at a Washington Hotel,” The Sunday Star, December 13, 1925.

- 2 Hughes, Langston, The Big Sea (New York: Hill & Wang, 2020), 122.

- 3 Ibid., 126.

- 4 Ibid., 124.

- 5 Ibid., 125.

- 6 Williams

- 7

Hughes, Langston, “Mother to Son,” The Crisis, Vol. 25, No, 2 (1922): 87.

- 8

“Vachel Lindsay,” Poetry Foundation.

- 9 Hughes, The Big Sea, 127.

- 10 Williams

- 11 Hughes, The Big Sea, 127.

- 12 Hughes, The Big Sea, 128.

- 13

Hughes, Langston, “The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain,” The Poetry Foundation.

- 14 Hughes, The Big Sea, 123.

- 15

“Langston Hughes,” Poetry Foundation.

- 16

“Our Story,” Busboys And Poets.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)