In 1985, Revolution Summer Sparked New Activism for D.C.'s Punk Rockers

The first fliers that appeared in the mail in the summer of 1985 seemed inconspicuous enough. All of them, though, were emblazoned with a slogan:

“Be on your toes. This is Revolution Summer.”

The fliers had originated from the Neighborhood Planning Council office, where punk music fan and Dischord Records employee Amy Pickering and her friend Chris Thomson were working as part of Marion Barry’s Summer Jobs program. Initially beginning as an inside joke about a revolt against their unpopular supervisor, the phrase made its way onto promotional posters for punk shows that summer. “NPC paid for everything, they had the Xerox machine, they had the stamps, they had envelopes. We had a lot of energy at this point and we thought maybe we could inspire other people,”1 Pickering said. The posters were initially sent out to members of what had once been the DC hardcore scene.

Ever since the breakup of two of the scene’s core bands – Minor Threat and the Faith – in 1983, punk in DC seemed to have lost its purpose. Hardcore as a musical idea had largely been beaten to death and what had once been an intimate scene had experienced an inundation of teenage fans the bands were ill-equipped to handle. Many members of the original hardcore scene had gone away to college – so instead of playing to a group of friends, bands were playing to crowds of strangers. As an influx of kids from the suburbs became involved in the scene, singer of California band Black Flag and DC native Henry Rollins asked, “are you really into this? [Or] are you showing up because this was covered in the Washington Post?”2

Crowd behavior at shows was a particularly pressing problem for performers and concertgoers alike. An influx of violent slamdancing – where ‘dancers’ would move with their limbs flailing in a combatant way – led crowd and band members alike to feel unsafe at shows. Ian MacKaye, the former frontman of Minor Threat, realized the practice was “a mask for violence,”3 which transferred over to some fans’ vandalism of venues during hardcore shows. The headline of the February 1985 newsletter Chow Chow Times was emblazoned with a grim reaper next to a tombstone with the names of DC venues on it – either because they had gone out of business or because hardcore shows had been banned for the destruction of property that occurred.4 A situation that was “quite petty and easy to resolve if you treat other peoples’ property with respect”5 seemed impossible for some fans to wrap their heads around. The desperate state of show culture led John Stabb of Government Issue to write an editorial for a local zine in which he proclaimed, “Do you want a football game or a show?”6

Slamdancing also caused a lot of women – who were already outnumbered by men – to distance themselves from the scene. Women like Pickering “began to feel excluded—by force…Slam dancing and stage-diving were separating the boys from the girls.”7 It didn’t help that many women weren’t seeing themselves represented in the bands they enjoyed.8 While women were still actively engaged in punk from behind the scenes, taking photos at shows or creating fanzines, there were very few female performers. Sharon Cheslow of the band Chalk Circle called on male members of the scene to better support the women involved.

“So many of us women were saying there’s something wrong here, we’re noticing these differences. We’re not getting the encouragement and support that we need, and how can we change things on this bigger level if we can’t change things right here in our community?”9

The former DC scene was beginning to fracture in two. One faction was made up of increasingly violent teenagers. The other, which was in part made up of people associated with MacKaye and Jeff Nelson’s record label Dischord, consisted of people who were disappointed with what the scene had become. Many insiders were frustrated. Mark Andersen, a Montana native who had moved to DC, expressed the frustration of many by writing short essays in local zines. In one piece he wrote, “…just criticizing…is not nearly enough. We’ve all got to start looking in the mirror more often because…change comes from the inside.”10 The pieces he wrote were equally parts advice and critique.

In October 1984, members of the “Dischord Crowd” came up with an idea they hoped would revitalize DC punk. They planned to form new bands around “Good Food Revival,” named for the celebratory feast they intended to hold. But, according to MacKaye, “it didn’t happen, there was some bad vibe going on or something…”11 Pickering later realized, “we had to get our sh*t together before we could help anyone else.”12

October came and went and the scene continued to stagnate. Or so it seemed.

A new band was beginning to make waves on the surface of the punk scene. After only two shows, Rites of Spring had attracted the attention of several core members of the former scene, including MacKaye. This was due in part to their new, unusual sound – which featured careening, melodic guitars, and introspective lyrics from singer Guy Picciotto.

Simultaneously, the band also garnered attention for destroying their equipment during gigs.13 MacKaye recalls their second show:

“They were dirt…poor, and Guy smashes a guitar and Eddie turns around and smashes his guitar and runs it through his speaker cabinet. Then Brendan kicks the drums, punches holes through all of them. Then they were totally out of equipment. It was kind of tragic.”14

It is no surprise then that Rites of Spring shows were infrequent. But they were always momentous occasions – the stage would be covered in flowers at the beginning of the show and elaborately designed setlists were placed in clear view above the stage. And despite it looking “like we’re playing with a lot of despair or emotion or frustration,” Picciotto acknowledged, “we’re at the same time joyful -- it’s the greatest moment of relief, our playing time. The moving, the music, everything about it, there’s so much joy.”15

With the opportunity in October having come and gone, several punks regrouped. The following spring, MacKaye remembers, Pickering made the decision that, “this summer we’re going to do it, summer ‘85. Revolution Summer.”16 Much of the inspiration came from what musicians were seeing on the streets of Washington.

Since November 21, 1984, protestors had been gathered outside the South African embassy, beginning with a sit-in contingent on the passage of sanctions preventing the US from trading with South Africa so long as apartheid was instated. By the following summer, however, it seemed to some that the protests were becoming routine. And punks like Pickering felt compelled to make an impact, after seeing that some of the protest’s leaders were around their age. “It was really nice to hang around and goof off at NPC, but then. There were the South Africa protests and I thought, ‘Man, here we are just being lunkheads.’”17

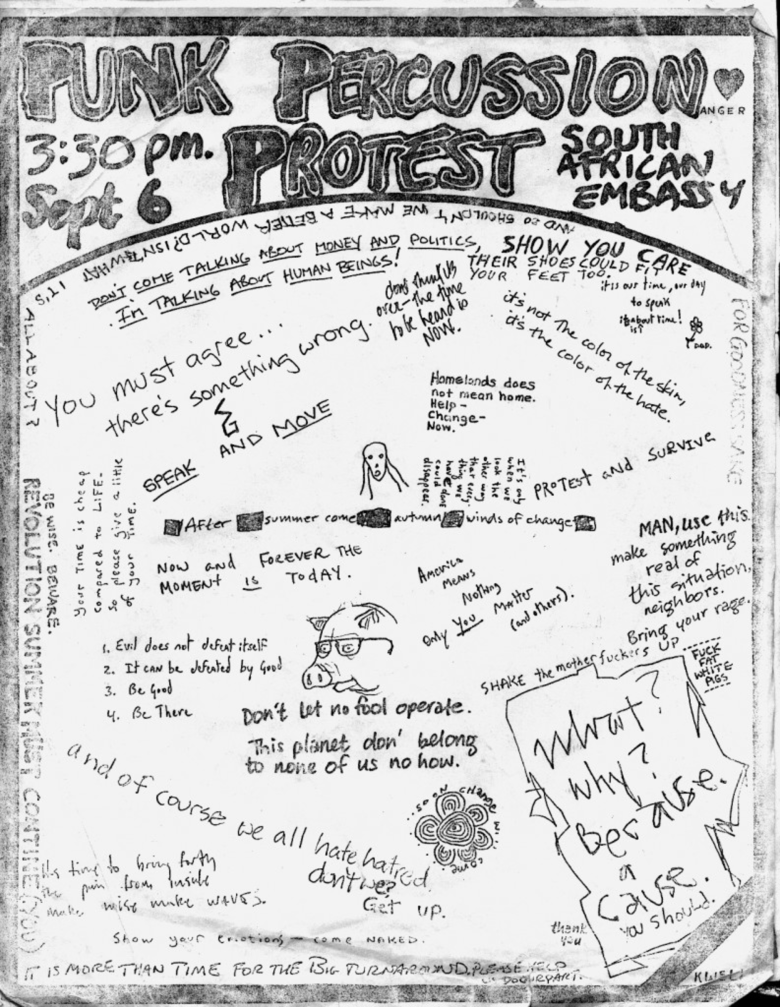

The punks’ ideas finally began to come into fruition on June 14th, 1985. Rites of Spring were slated to play at the Chevy Chase Community Center – it was there the band announced that the first “Punk Percussion Protest” would be held at the South African Embassy next week.

But the show was special for other reasons – and it seems to have begun when the members of Rites of Spring walked offstage at the end of their set. After playing their final song, “End on End” – a song appropriately about renewal – the band left the stage only to realize that “The whole audience joined in for one long ‘whoaaaaa’ chorus”18 – they were singing the background vocals of the song.

Finally, the musicians made their return to the stage and joined the crowd in a reprise of the song in a moment Andersen described as “full as life can be.”19 He continued: “Although the band was the catalyst, the evening went far beyond them, was far more than a mere ‘concert.’” Reflecting on earlier days of the DC hardcore scene in 1981 and 82, a reviewer wrote in Yet Another Unslanted Opinion that “back then it was like change in the air or something, that’s what it was like at this show too.”20

There was something alive in the air that night – the performers and attendees alike realized that this show was a rebirth – a new scene was being born out of the old.21 A new crop of bands popped up in Rites of Spring’s footsteps, such as Embrace – made up of former members of the Faith and fronted by Ian MacKaye -- and Beefeater – a band known for their staunchly political lyrics and vegetarianism. A new community of younger bands were also forming in Northern Virginia that reminded the older punks of the late ‘70s and early ‘80s – notable among these was Mission Impossible.

The first day of summer 1985 – June 21st – was heralded as the beginning of the punks’ activism when members of several bands decided they “wanted to create a spontaneous group of people who would go down”22 to the South African Embassy and stand out from the Trans Africa protesters. Standing on the opposite side of the street from other demonstrators, the punks made sure their voices – or rather, drums – were heard. “It’s a very effective form of protest,” explained Mark Sullivan of the band Kingface. “The Trans Africa people are down there everyday, but you have to protest a block and a half away from the Embassy. When we go down there and everybody is marching around beating on drums or whatever to make noise, you can hear it three or four miles away which means they can hear it inside the Embassy.”23

The Punk Percussion Protests became a critical part of the punks’ new activism. They became a mainstay within the punk scene, even garnering national attention in 1991 when protests of the Gulf War had then-President George H.W. Bush complaining that “those damned drums are keeping me up all night.”24

That night, Rites of Spring kicked off a show at 9:30 Club. Picciotto thanked the audience for attending the protest. “Punk is about building things, not destroying them,” he said to the audience, in ironic contrast to the band, who had become notorious for quite literally destroying all their instruments.25 Once again, the band ended their set with “End on End,” and Picciotto tore the strings off his guitar, trashing his instrument. With the singer “crumpled on the stage,” once again “the lights went out, yet everyone kept si[n]ging and clapping until the band returned.”26 After taking the stage again, the band launched into “All There Is.” At the song’s peak, Picciotto shouted into the crowd, “it doesn’t have to end, no end, I said, no end!”27

Although Revolution Summer did end (all of the major bands of that summer, including Rites of Spring, didn’t survive to see 1986), it spawned a greater political consciousness among hardcore bands – “rather than simply looking inward, the new music” created by bands during Revolution Summer “demanded that the listener look outward as well.” The bands that formed as a result reflected a new consciousness within the scene, beginning to make space for women in bands – including the all-female band Fire Party, featuring Pickering on vocals and guitar –predating the Riot Grrrl movement.

Inspired by the revitalization of the punk scene in the summer of 1985, Mark Andersen and Kevin Mattson founded Positive Force, an organization that sponsored hundreds of benefit concerts and protests for various causes, including the protest that would prevent President Bush from getting his beauty sleep. They began issuing a free zine which contained information for people to educate themselves about current events, as well as successful reports of collective action from across the US.

Although Revolution Summer led to a revitalization of the DC punk scene, it also reflected increasing insularity. The newly formed bands tended to book shows with each other, rather than including older groups. “It felt like the bands like us [Government Issue] and Scream and Marginal Man…were left out of the party,” said John Stabb of Government Issue. “We were not invited.”28 These bands were left to deal with the violent punk fans who would get kicked out of the new bands’ shows.29

Revolution Summer may not have solved the DC punk scene’s problems, but it created a space where people could enjoy the music and get involved in their community. Author Andy Greenwald remarked that “What had happened in D.C. in the mid-eighties…was in many ways a test case for the transformation of the national punk scene over the next two decades.”30 As Picciotto would note, “You’ve got to try to stir people and try to get into them and have them get into you, which is what I hope our shows are about. I would say that the way we play is a protest.”31

Footnotes

- 1 Andersen, Mark, and Mark Jenkins. Dance of Days: Two Decades of Punk in the Nation’s Capital. Updated and Expanded 4th ed. New York: Akashic Books, 2009.

- 2 Punk the Capital: Building a Sound Movement, (Metuchen, NJ: Passion River Films, 2021), 88 min.

- 3

Salad Days: A Decade of Punk in Washington, DC (1980-90) (2015). Accessed October 11, 2023.

- 4

"Chow Chow Times, Issue 2, February 1985 | Digital Collections @ the University of Maryland.” Accessed November 6, 2023.

- 5

"Chow Chow Times, Issue 2, February 1985 | Digital Collections @ the University of Maryland.” Accessed November 6, 2023.

- 6

“Metrozine Fanzine, Issue 7, 1985 | Digital Collections @ the University of Maryland.” Accessed November 8, 2023.

- 7

Blush, Steven, and George Petros. American Hardcore: A Tribal History. 2nd ed. 1 online resource (403 pages) : illustrations vols. Los Angeles, Calif.? Feral House, 2010. Pg 154.

- 8

An exception to this would be the band Madhouse, fronted by singer Monica Richards. However, Richards was frequently met with aggression at shows, especially after sharing that the content of some of her lyrics discussed sexual assault. For more see Salad Days: A Decade of Punk in Washington, DC (1980-90) (2015). Accessed October 11, 2023.

- 9

Salad Days: A Decade of Punk in Washington, DC (1980-90) (2015). Accessed October 11, 2023.

- 10

“Yet Another Unslanted Opinion, Number 1...” Accessed November 22, 2023.

- 11

“Flipside, Issue 47, September 1985 | Digital Collections @ University of Maryland Libraries.” Accessed December 8, 2023.

- 12 In truth, the Dischord label was in no shape to be putting out new releases, being several thousand dollars in debt, and there were no new bands coming out of the area to record. Andersen, Mark, and Mark Jenkins. Dance of Days: Two Decades of Punk in the Nation’s Capital. Updated and Expanded 4th ed. New York: Akashic Books, 2009.

- 13

According to the band themselves, the “mysteries” of their instruments breaking could be traced back to a creature called “The Watcher.” Reportedly “raised” in drummer Brendan Canty’s house, the Watcher took form “as a ceramic horse,” and despite figuring out “he was biting our strings off, and breaking stuff…” and hanging him on the porch of Dischord House, “he still comes to our shows, we don’t know how he gets there…” for more check “Flipside, Issue 47, September 1985 | Digital Collections @ University of Maryland Libraries.” Accessed December 8, 2023.

- 14 Azerrad, Michael. Our Band Could Be Your Life: Scenes from the American Rock Underground 1981-1991. 1st ed. Boston: Little, Brown, 2001.

- 15

“Flipside, Issue 47, September 1985 | Digital Collections @ University of Maryland Libraries.” Accessed December 8, 2023.

- 16

“Flipside, Issue 47, September 1985 | Digital Collections @ University of Maryland Libraries.” Accessed December 8, 2023.

- 17 Andersen, Mark, and Mark Jenkins. Dance of Days: Two Decades of Punk in the Nation’s Capital. Updated and Expanded 4th ed. New York: Akashic Books, 2009, 162.

- 18

“Metrozine Fanzine, Issue 10, circa 1985 | Digital Collections @ the University of Maryland.” Accessed November 8, 2023.

- 19 Andersen, Mark, and Mark Jenkins. Dance of Days: Two Decades of Punk in the Nation’s Capital. Updated and Expanded 4th ed. New York: Akashic Books, 2009.

- 20

“Yet Another Unslanted Opinion, Number 2...” Accessed November 9, 2023.

- 21 Of course, it wouldn’t have been a Rites of Spring show without the band destroying their instruments – after the encore, Scott Crawford wrote that “Brendan [Canty] runs on and demolishes his drumset.”

- 22

"Flipside, Issue 47, September 1985 | Digital Collections @ University of Maryland Libraries.” Accessed December 8, 2023.

- 23

“Flipside, Issue 47, September 1985 | Digital Collections @ University of Maryland Libraries.” Accessed December 8, 2023.

- 24 “The Drums of Protest,” New York Times, February 6, 1991, sec. INTERNATIONAL.

- 25 Azerrad, Michael. Our Band Could Be Your Life: Scenes from the American Rock Underground 1981-1991. 1st ed. Boston: Little, Brown, 2001.

- 26

“Yet Another Unslanted Opinion, Number 2...” Accessed November 9, 2023.

- 27

Rites Of Spring - All There Is - Live 1985 Old 9:30 Club, 2006.

- 28

Salad Days: A Decade of Punk in Washington, DC (1980-90) (2015). Accessed October 11, 2023.

- 29

Members of the Revolution Summer crowd seemed aware of this as well. When asked his opinion of the DC scene, Picciotto replied, “there seems to be two different scenes. One which I definitely disapprove of and one I wouldn’t.” For more see “Yet Another Unslanted Opinion, Number 2...” Accessed November 9, 2023.

- 30

Greenwald, Andy. Nothing Feels Good: Punk Rock, Teenagers, and Emo. 1st ed. New York: St. Martin’s Griffin, 2003.

- 31 Andersen, Mark, and Mark Jenkins. Dance of Days: Two Decades of Punk in the Nation’s Capital. Updated and Expanded 4th ed. New York: Akashic Books, 2009.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)