The Rise and Fall of D.C.'s Uptown Theater

On June 8, 1993, Connecticut Avenue roared to life. Snapping photos and waving dinosaur-emblazoned posters, local fans crowded the sidewalks, each hoping to catch a glimpse of A-list movie stars—and, of course, Hill politicians—who had come out for the world premiere of Jurassic Park.

The star-studded premiere doubled as a benefit for the Children’s Defense Fund, a national nonprofit that provides funding for children’s education, health care, and racial justice.1 “The invitation suggested dino-size contributions,” reported The Washington Post. “Guests could be a T. rex for $50,000, brachiosaur for $25,000, triceratops for $10,000, velociraptor for $5,000 or dilophosaur for $500.” The event raised a quarter of a million dollars from its attendees, many among them congressmen who were thrilled at the novelty of a movie premiere in the Nation’s capital.

"This is the biggest dinosaur Hollywood has sent to Washington since Ronald Reagan," said Henry Waxman, a Democratic Representative from California.

"I love Crichton's writing, and I think Spielberg's a genius,” remarked Vermont Senator Patrick Leahy, also a Democrat. "And I am unabashedly the biggest movie buff in the U.S. Senate."2

Premiering a science fiction blockbuster like Jurassic Park in Washington, D.C. might’ve seemed a strange choice. The nation’s capital is not exactly known for its dinosaurs (sorry, Capitalsaurus).

But the Uptown Theater was special.

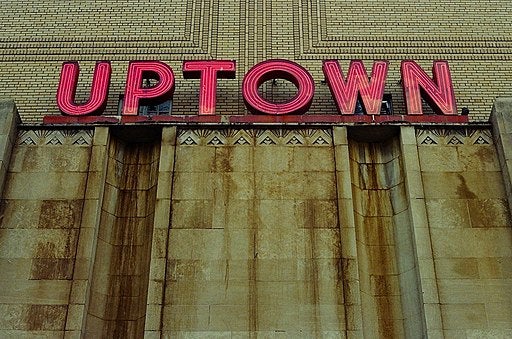

As The Washington Times reported when its doors first opened in 1936, “Exterior treatment is of white limestone and pink polished granite, very ritzy… The lobby walls are imported Scaviola marble in delicate shades, if you care.”3

Many people did care – a lot. On opening night, the theater boasted a stacked guest list of affluent business owners and influential Northwest community leaders for a showing of Cain and Mabel. Many among them, such as District Surveyor Melvin C. Hazen, saw The Uptown as a beacon of cultural advancement for its patrons.4 These patrons were Cleveland Park’s exclusively White residents, because the theater opened in an era when local representatives, among them Hazen himself, sought to clear out non-white developments from the area.5

However, the theater changed with the integration of District movie theaters in 1953,6 and it soon became an iconic staple for all Washingtonians.

Over the years, The Uptown hosted several notable film premieres, which often doubled as fundraisers. In 1962, for example, the Washington opening of The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm doubled as a donation-drive for the Metropolitan Police Department.7 In 1990, Dances with Wolves premiered as a fundraiser for the planned National Museum of the American Indian.8

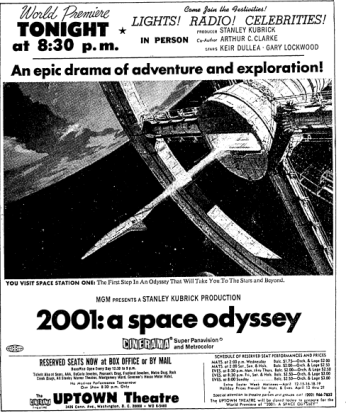

The Uptown wasn't just notable for its beauty, but its technological advancement. Continuously on the front lines of film innovation, The Uptown was host to the world premiere of Stanley Kubrick's groundbreaking film, 2001: A Space Odyssey in 1968, and ran the film for an entire year. The theater was the only one in the city which boasted a Cinerama screen, curved and split three ways, where the movie appeared larger-than life and practically tangible.9

“When they did the Cinerama screen it became one of the prestige houses in the country,” said NPR arts critic Bob Mondello. “That’s why they opened 2001: A Space Odyssey there rather than in New York. Because it was just a great house.”10

For decades, District residents craving stunning visuals agreed that The Uptown was unbeatable. In 1977, it was the sole DC theater to screen Star Wars in its initial run, wreaking havoc on Connecticut Avenue as avid fans spilled into the street for weeks on end.

“The Uptown is the coolest theater—the most historic, the most iconic,” said Erik Janniche, who helped organize camp-outs at The Uptown for the Star Wars prequels. “If you’ve never been there before, you’re kinda taken aback at first. When the curtains open, they just never stop opening. They keep going and going and going. And the sound system was state of the art back in the ’90s. Now every theater has an awesome sound system.”11

The Uptown also proved to be one of the most resilient movie houses in D.C.: by the 2000s, many other classic cinemas had caved. Some, like the Apex Theater in the Spring Valley neighborhood, were demolished decades before.12 Others like the MacArthur Theater in the Palisades or the Newton Theater in Brookland maintained their historic facades but became other businesses. All three, along with The Uptown, were designed by iconic DC architect John Jacob Zink.13

With the advent of at-home streaming in the 2000s, subscription services and movie tickets grew side-by-side in revenue for the next decade. But in-person attendance dwindled because a single ticket could cost as much as a monthly fee for unlimited films.14Even more pronounced was the dip in attendance for small, independent theaters. Competition from large theater chains was so intense that hundreds of independent theaters buckled under the pressure to close in the digital age.15

Perhaps due to its big-brand operators, The Uptown managed to remain a destination into the 2010s. The cinema had changed hands multiple times: in the late 1970s, it was bought by the local Pedas brothers, who then leased the building to various screening companies.16 The last to operate The Uptown was AMC.

But its success could not last forever.

“When I thought about it, I realized my most recent memory of being in a more-than-half-full Uptown audience was for a Saturday matinee of Gravity in 2013,” reflected local writer Chris Klimek. “The last time I’d stood in a long line stretching south down Connecticut Avenue waiting to for the Uptown’s doors to open—a custom that once attended the release of every new blockbuster—was for Iron Man 3, half a year before that.”17

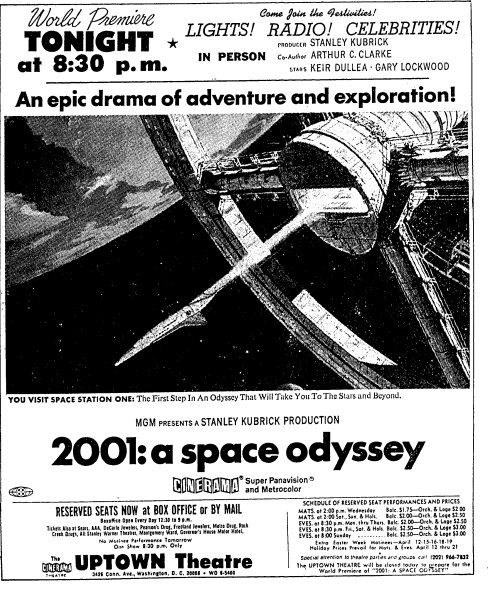

Despite thinning crowds, loyal moviegoers were happy that the theater was still running. But AMC faced backlash in 2017 when they attempted to take control of the theater’s iconic façade.

“The Uptown is not just another movie screen in a ‘multi-plex’ in some suburban shopping mall,” wrote a Cleveland Park Listerv user, ‘Eleanor O.’

AMC had sought a hearing with the D.C. State Historic Preservation Office to replace the theater’s historic bulb-lined sign with a company logo. Upon catching wind of its plans, outraged Cleveland Park residents sent a flurry of phone calls and emails to AMC representatives.18 “It is a landmark! […] It is our part of town and there was an uptown before there was a movie house and long before there was an AMC!”19

Residents swiftly warded off AMC’s plans, halting the original sign’s destruction. “We appreciate the passion and feedback from the community,” said communications representative Ryan Noonan, “and look forward to serving moviegoers at AMC Uptown 1 for years to come.”20

The signage success was widely celebrated in the neighborhood, but it couldn’t stop what was to come. After 84 years of operation, AMC announced the end of The Uptown in 2020.21 The move came days before the national shutdown due to COVID-19, and the pandemic left a vacancy in the building that has yet to be filled.22

In 2021, WTOP reported that talks with Landmark Cinemas were in progress for operation of The Uptown. However, the company was noncommittal. “There really is no story at present,” said Landmark’s Vice President of Marketing & Publicity, Margot Gerber. “Seems [Cleveland Park residents] are over eager for something to happen with this beautiful theater.”23

In 2022, residents did succeed in having the Theater recognized as a Historic DC Landmark. The Waterfall Moderne stonework, and—yes—the iconic sign, have been saved from destruction. The designation also recommended further research into The Uptown’s segregated past as it moves into a possible new era of operation.24, 25

“We've seen old movie theaters turned into pharmacies and Burger Kings before. This will not happen here,” wrote neighborhood representative Sauleh Siddiqui in 2020. But he conceded that, “we may need to be creative about how to find a suitable replacement and allow for uses in addition to it being a theater.”26

Bill Durkin, a former attorney to the Uptown’s owners, remarked before its closing that “a single theater of that size is a relic, a dinosaur.”27 But community advocates remain hopeful that the beloved movie palace can still be brought back to life, despite all odds, years after its extinction.

Footnotes

- 1

Children’s Defense Fund. “About Us.” Accessed July 9, 2024.

- 2

Roberts, Roxanne. “NIGHT OF THE LIVING DINOSAURS.” Washington Post, January 4, 2024.

- 3

The Washington Times. “Uptown Theater Opens.” October 30, 1936.

- 4

The Washington Times. “Uptown Theater Opens.” October 30, 1936.

- 5

"Acquirement of Reno Subdivision in the District of Columbia.” Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1926. Pg 3.

- 6

Quigley, Joan. “How D.C. Ended Segregation a Year before Brown v. Board of Education.” Washington Post, January 15, 2016.

- 7

Evening Star. “Club Plans To Sponsor Premiere.” October 19, 1962. Library of Congress.

- 8

Klimek, Chris. “An Oral History of the Uptown Theater.” Washington City Paper, August 2, 2018.

- 9

Zoldessy, Michael. “‘2001: A Space Odyssey’ 45th Anniversary – The Cinerama Engagements.” Cinema Treasures. Accessed July 9, 2024.

- 10

Klimek, Chris. “An Oral History of the Uptown Theater.” Washington City Paper, August 2, 2018.

- 11

Klimek, Chris. “An Oral History of the Uptown Theater.” Washington City Paper, August 2, 2018.

- 12

Cinema Treasures. “Apex Theater in Washington, DC.” Accessed July 9, 2024.

- 13

Vinopal, Courtney. “You’ll Feel Nostalgic Looking At These DC Theaters That Have Held Onto Their Old Look” August 2, 2017.

- 14

Corkery, Caelan. “Trends: From Movie Theaters to Netflix: Streaming Services Are Here to Stay.” The Dartmouth, October 24, 2022.

- 15

Donnelly, Brent Lang, Matt, Brent Lang, and Matt Donnelly. “Inside Indie Movie Theaters’ Battle to Survive.” Variety (blog), March 26, 2019.

- 16

Schwartzman, Paul. “Uptown Theater, an Iconic D.C. Movie Palace, Shuts Down.” Washington Post, March 14, 2020.

- 17

Klimek, Chris. “An Oral History of the Uptown Theater.” Washington City Paper, August 2, 2018.

- 18

Stein, Perry. “For a Few Days, a Neon Sign and a Corporation’s Failed Plan United Cleveland Park Residents.” Washington Post, July 31, 2017.

- 19

O, Eleanor. “Re: Uptown Theater Sign.” ClevelandPark Listerv, July 28, 2017.

- 20

Stein, Perry. “For a Few Days, a Neon Sign and a Corporation’s Failed Plan United Cleveland Park Residents.” Washington Post, April 8, 2023.

- 21

Fraley, Jason. “Uptown Theater, Historic Host of ‘2001,’ ‘Jurassic Park’ Premieres, Closes in DC.” WTOP News, March 13, 2020.

- 22

Basch, Michelle. “Uptown Theater Named a DC Historical Landmark.” WTOP, June 29, 2022.

- 23

Fraley, Jason. “Is the Uptown Theater Returning to DC? Here’s What We Know so Far.” WTOP News, October 14, 2021.

- 24

Basch, Michelle. “Uptown Theater Named a DC Historical Landmark.” WTOP, June 29, 2022. Miller, Rebecca, and Rick Nash.

- 25

“HISTORIC PRESERVATION REVIEW BOARD APPLICATION FOR HISTORIC LANDMARK OR HISTORIC DISTRICT DESIGNATION.” Government of the District of Colubia Historic Preservation Office, October 29, 2020.

- 26

Siddiqui, Sauleh. “My Candidacy for ANC 3C05 - Save the Uptown.” ClevelandPark, March 13, 2020.

- 27

Schwartzman, Paul. “Uptown Theater, an Iconic D.C. Movie Palace, Shuts Down.” Washington Post, March 14, 2020.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)