As World War II Raged, “Lady Death” Came to Washington

In late September of 1942, a young woman called “Lady Death” is rattling up the railway tracks to Washington D.C. In her pocket she has a dictionary inscribed by Stalin himself, and she surveys the Virginia countryside out the window with the careful eye of a prolific sniper. Her first stop will be the White House, where President Roosevelt is waiting for her.

That may sound like the beginning of a spy thriller, but in reality, the sniper has come only as a diplomat. A soldier, a Soviet citizen, and a woman besides, Americans received her as a curiosity and a marvel—more than she would have liked, when she had such important things to say. She did, however, find a brief ally and lifelong friend in Eleanor Roosevelt.

Lyudmila Pavlichenko was born outside of Kiev in 1916. A tomboyish child, she refused to let the neighborhood boys outdo her “in anything.”1 While studying history at Kiev University, she joined a rifle club and earned a certificate for marksmanship. When the Nazis invaded the USSR in 1941, she successfully auditioned to become a Red Army sniper.

Despite facing pressure to become a nurse instead, Pavlichenko turned out to be the most effective of the USSR’s 2,000 female snipers, and one of the best in the entire Army. Fighting in the sieges of Odessa and Sevastopol, she was a patient, accurate, and deadly soldier. In 1942, with 257 kills and a reputation as a dependable countersniper, she was promoted to Lieutenant. The Soviets began to call her “Lady Death.” The Nazis coined the more acerbic “Russian Bitch from Hell.”2 Her “score” of confirmed kills reached 309—but those were only the ones officially corroborated by a witness.3 A more accurate figure may be over 500.4

In 1942, a successful days-long duel against a German sniper on a bombed-out bridge made her superiors consider Pavlichenko’s potential as a propaganda tool. She began addressing meetings and assemblies, though she was “reluctant” to do so and resisted “largely untruthful” propaganda pieces written about her.5

In August, President Roosevelt telegraphed Stalin to say he would convene an International Student Assembly in Washington with young people from 29 nations. He was requesting Soviet representatives, preferably students who had experienced combat. The most obvious candidate was Pavlichenko, alongside Nikolai Krasavchenko, a Young Communist Leader, and Vladimir Pchelintsev, another sniper. They would represent the USSR at Roosevelt’s Assembly, but Stalin sent them to America with another mission: to convey the “life and death struggle” on the Eastern Front, convincing the Americans to open a second front in Europe and taking pressure off the embattled Soviets.6

The delegation arrived in Washington on September 27. Their first stop was the White House, which was “reminiscent of the country estate of some gentleman with an income which was regular, but certainly not extraordinary.”7 Eleanor Roosevelt herself received them for breakfast. During the meal, she remarked that “it would be hard for American women to understand” Pavlichenko, since she shot so effectively to kill.

A little insulted, she responded coldly: “An accurate bullet [is] no more than a response to a vicious enemy.”8

Pavlichenko knew she was “prejudiced” against Eleanor as an “aristocrat, millionairess, member of the exploiting class.” However, the First Lady later apologized and as Pavlichenko got to know her better, she came to know her as a woman of “enormous charm, intelligence, and kindness,” who was a “well-known and respected public activist, journalist, and ‘minister’” for the Roosevelt administration.9

Another trait endeared the First Lady to the Soviet sniper: she was a daring driver who raced her convertible “through the Washington streets like a tornado.”10

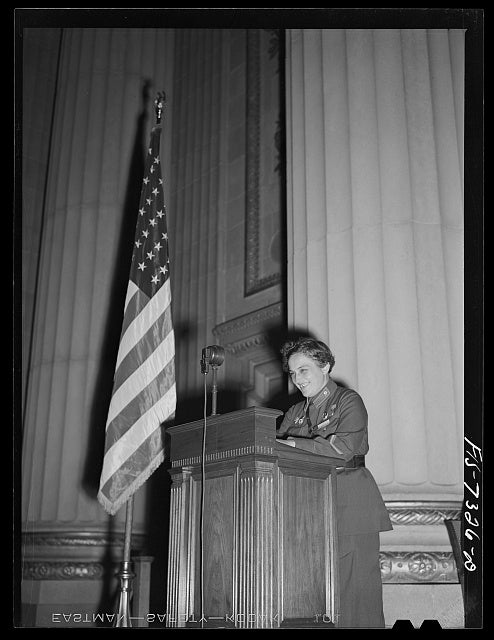

In the afternoon, the delegation traveled to the Soviet embassy for a “formal and quiet” banquet followed by a press conference. Pavlichenko spoke after Krasavchenko and Pchelintsev: from a script, she “convey[ed] greetings from Soviet women… fighting in the front ranks against the bloodthirsty fascists”, spoke about the Soviets’ struggle against the Nazis, and asked the Allies to open second front in Europe.11

She expected the journalists to ask questions about the prepared statements, but they instead “tried to fish for something that had not been voiced.”12 Many of the questions were directed at her, which was unsettling. Pavlichenko was shy and her training as a sniper had sensitized her to clamor and crowds.13

One reporter wanted to know: could she take hot baths at the front?

“Absolutely,” Pavlichenko replied. “If you are sitting in a trench and there is an artillery attack, it gets hot… It tends to be a dust bath.”

What about lipstick; were female soldiers allowed to wear any?

“Yes, but they don’t always have time. You need to be able to reach for a machine gun, or a rifle, or a pistol.”

Pavlichenko compared the “stupid” and often sexist questions from reporters to “German ‘psychological attacks’” in which “the enemy wanted to frighten, shock, and dislodge us.” When she answered, “passion and excitement” often got the better of her.14

One male reporter asked her what color underwear she preferred to wear beneath her uniform. This shocked and infuriated Pavlichenko.

“In Russia you would get a slap in the fact for asking a question like that,” she said. “I will be happy to give you a slap. Come a bit closer—”15

The reporter, wisely, did not.

News about Pavlichenko made a splash; reports often veered into the demeaning or diminutive. Malvina Lindsey, who wrote “The Gentler Sex” column for the Washington Post, titled her article on Pavlichenko, “Step-Ins for the Amazons.” Wondering why the sniper saw the reporters’ questions as such an insult, she pondered: “Isn’t it a part of military philosophy that an efficient warrior takes pride in his appearance? Isn’t Joan of Arc always pictured in beautiful and shining armor?”16

Pavlichenko was most frustrated by the fact that anyone could consider shining armor a possibility in wartime. She had suffered four wounds during her service, her first husband had been killed by a German shell. On her very first mission, a fellow sniper (“a nice, happy boy,” as she described him) was shot next to her as they were setting up their positions.17 Pavlichenko knew better than most the messy nature of war and the toll it exacted on everyone it touched.

Whether her uniform was clean or dirty, flattering or not, was the wrong thing for the Americans to focus on. Simmering with indignance, she told reporters that she was “proud” to wear it, because it “ha[d] been sanctified by the blood of my comrades who've fallen in combat with the fascists.”18

In an interview with TIME, Pavlichenko was “amazed” that she had been subjected to such “silly questions” in Washington. “Don’t they know there is a war?” she asked.19

Eleanor Roosevelt noticed and sympathized with Pavlichenko’s frustration. At a separate reception, she showed Pavlichenko a column written by an acquaintance, Elsa Maxwell, which was much more acclamatory: “Lieutenant Pavlichenko[‘s]… imperturbable calm and confidence come from what she has had to endure and experience… Her olive-colored tunic with red markings has been scorched by the fire of combat.”

To Eleanor, this was a more than accurate description. “You carried yourself well,” she told Pavlichenko.20

It was also Eleanor who introduced the delegation—“our new Soviet friends”—to President Roosevelt. When he met the three delegates, he spoke with Pavlichenko first, “like a true gentleman.” He wanted to know “what fighting I had been involved in, what I had received my military decorations for, how my regimental comrades had fought.”21

Regarding a new front, the President was less accommodating. He blamed the English for stalling any American invasion initiatives, but reassured Pavlichenko that “in their heart and soul the American people are with our Russian allies.”22 The new front would come in due time.

By the end of September, the Soviet delegation’s time in Washington was at an end. But Pavlichenko continued her US tour in Chicago, Minneapolis, Denver, Seattle, and through California. Eleanor Roosevelt “often” accompanied the Soviet delegation; when she was present the “level of meetings” they could secure was much higher.23

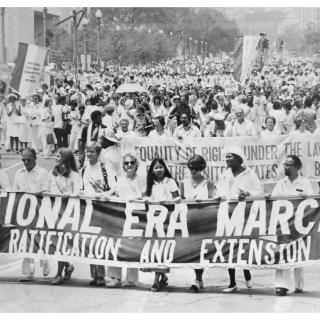

Day by day, Pavlichenko found her footing when speaking with the American press. She had been assigned to a “new section of the front,” and her new “battle” was against the journalists. To spar with them she had “to be sincere, confident… extremely collected, jovial and witty. Then they would believe us.”24 She spoke about her combat experiences, the brutal effects of the Nazi invasion of the USSR, and her nation’s progress on gender equality (“Whatever we do, we are honored not just as women, but as individual personalities, as human beings”).25

In Chicago, she addressed a crowd in Grant Park, mostly “men between thirty and forty… looking at [Pavlichenko] quite affably and smiling.”26

“Gentlemen,” she challenged through her interpreter. “I am 25 years old and I have killed 309 fascist occupants by now. Don’t you think, gentlemen, that you have been hiding behind my back for too long?”27

Before Pavlichenko’s American tour came to a close, Eleanor Roosevelt invited the Soviet delegates to Hyde Park, the Roosevelt estate in New York. There, Pavlichenko spent more time with the President and his wife. Eleanor even altered a set of her own pajamas for Pavlichenko (who was surprised a president’s wife possessed such a skill). As she changed, Eleanor caught sight of a “long, reddish, forked scar” arcing from her shoulder to her spine.28 When Eleanor asked where it had come from, Pavlichenko replied that it was a shrapnel wound from Sevastopol (one of four combat wounds she suffered).

According to Pavlichenko, the First Lady “impulsively hugged me and brushed my forehead with her lips,” saying, “What dreadful ordeals you’ve had to endure.”29

Later, Eleanor Roosevelt would recall her friend Lady Death fondly: “There is something very charming to me about the young Russian woman, Junior Lieutenant Lyudmila Pavlichenko. She has suffered… and is suffering something which is universal and binds all the world together regardless of language.”30

After she returned to the USSR, Pavlichenko and Eleanor continued corresponding about “family news,” “interesting literary items,” and their trips to peace congresses.”31 They met once more in 1957, when Eleanor was touring Moscow. She discovered Pavlichenko was living in a small two-room apartment in the city. Despite her restricted agenda and the protests of her Soviet government handler, Eleanor “persisted” until she was allowed to visit her friend.32

While the handler sat nearby, the two spoke “with cool formality” in Pavlichenko’s front room, until, with an invented excuse, the ex-sniper pulled her friend into the bedroom. Once the door closed, she threw her arms around Eleanor. The two reunited, “half-laughing, half-crying,” with Pavlichenko “telling [Eleanor] how happy she was to see her.”33 The First Lady attempted to bring Pavlichenko back to America for another visit, but the State Department denied her request. Lady Death remained in the USSR, now a research assistant at the Soviet Navy headquarters, until she passed away in 1974.

Reflecting on her visit to Washington, Pavlichenko summarized her impact in her memoir: “We [delegates] spoke about the war with too much passion, too much emotion… The war, which had previously been distant and incomprehensible to the Americans, suddenly acquired visible features.”34

It would be another two years before a second European front opened in Normandy, and another year still before the Nazis were defeated. The brutal time in which the Soviets alone faced the brunt of the Nazis’ armies would become a point of pride and resentment for decades to come.35 But in autumn of 1942, Lady Death found a tentative ally—and certainly a friend—in America’s First Lady, who during a cool evening on the White House lawn, “thanked us for [our visit] and voiced the hope that other residents of her native land… would hear what we had to tell.”36

Footnotes

- 1

King, Gilbert. “Eleanor Roosevelt and the Soviet Sniper.” Smithsonian Magazine, February 21, 2013. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/eleanor-roosevelt-and-the-soviet-sniper-23585278/.

- 2

- 3

King, Gilbert. “Eleanor Roosevelt and the Soviet Sniper.” Smithsonian Magazine, February 21, 2013. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/eleanor-roosevelt-and-the-soviet-sniper-23585278/.

- 4

Ross, Greg. “Podcast Episode 224: Lady Death.” Futility Closet, November 12, 2018. https://www.futilitycloset.com/2018/11/12/podcast-episode-224-lady-death/.

- 5

Ross, Greg. “Podcast Episode 224: Lady Death.” Futility Closet, November 12, 2018. https://www.futilitycloset.com/2018/11/12/podcast-episode-224-lady-death/.

- 6

Ross, Greg. “Podcast Episode 224: Lady Death.” Futility Closet, November 12, 2018. https://www.futilitycloset.com/2018/11/12/podcast-episode-224-lady-death/.

- 7

Pavlichenko, Lyudmila Mykhailvna. Lady Death: The Memoirs of Stalin’s Sniper. Simon and Schuster, 2018.

- 8

Pavlichenko, Lyudmila Mykhailvna. Lady Death: The Memoirs of Stalin’s Sniper. Simon and Schuster, 2018.

- 9

Pavlichenko, Lyudmila Mykhailvna. Lady Death: The Memoirs of Stalin’s Sniper. Simon and Schuster, 2018.

- 10

Pavlichenko, Lyudmila Mykhailvna. Lady Death: The Memoirs of Stalin’s Sniper. Simon and Schuster, 2018.

- 11

Pavlichenko, Lyudmila Mykhailvna. Lady Death: The Memoirs of Stalin’s Sniper. Simon and Schuster, 2018.

- 12

Pavlichenko, Lyudmila Mykhailvna. Lady Death: The Memoirs of Stalin’s Sniper. Simon and Schuster, 2018.

- 13

Ross, Greg. “Podcast Episode 224: Lady Death.” Futility Closet, November 12, 2018. https://www.futilitycloset.com/2018/11/12/podcast-episode-224-lady-death/.

- 14

Pavlichenko, Lyudmila Mykhailvna. Lady Death: The Memoirs of Stalin’s Sniper. Simon and Schuster, 2018.

- 15

Pavlichenko, Lyudmila Mykhailvna. Lady Death: The Memoirs of Stalin’s Sniper. Simon and Schuster, 2018.

- 16

Malvina Lindsay. "The Gentler Sex: Step-Ins for Amazons." The Washington Post (1923-1954), Sep 19, 1942.

- 17

King, Gilbert. “Eleanor Roosevelt and the Soviet Sniper.” Smithsonian Magazine, February 21, 2013. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/eleanor-roosevelt-and-the-soviet-sniper-23585278/.

- 18

Ross, Greg. “Podcast Episode 224: Lady Death.” Futility Closet, November 12, 2018. https://www.futilitycloset.com/2018/11/12/podcast-episode-224-lady-death/.

- 19

TIME. “Army & Navy – Lady Sniper.” Time, September 28, 1942. https://time.com/archive/6771260/army-navy-lady-sniper/.

- 20

Pavlichenko, Lyudmila Mykhailvna. Lady Death: The Memoirs of Stalin’s Sniper. Simon and Schuster, 2018.

- 21

Pavlichenko, Lyudmila Mykhailvna. Lady Death: The Memoirs of Stalin’s Sniper. Simon and Schuster, 2018.

- 22

Pavlichenko, Lyudmila Mykhailvna. Lady Death: The Memoirs of Stalin’s Sniper. Simon and Schuster, 2018.

- 23

Pavlichenko, Lyudmila Mykhailvna. Lady Death: The Memoirs of Stalin’s Sniper. Simon and Schuster, 2018.

- 24

Pavlichenko, Lyudmila Mykhailvna. Lady Death: The Memoirs of Stalin’s Sniper. Simon and Schuster, 2018.

- 25

King, Gilbert. “Eleanor Roosevelt and the Soviet Sniper.” Smithsonian Magazine, February 21, 2013. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/eleanor-roosevelt-and-the-soviet-sniper-23585278/.

- 26

Pavlichenko, Lyudmila Mykhailvna. Lady Death: The Memoirs of Stalin’s Sniper. Simon and Schuster, 2018.

- 27

Pavlichenko, Lyudmila Mykhailvna. Lady Death: The Memoirs of Stalin’s Sniper. Simon and Schuster, 2018.

- 28

Pavlichenko, Lyudmila Mykhailvna. Lady Death: The Memoirs of Stalin’s Sniper. Simon and Schuster, 2018.

- 29

Pavlichenko, Lyudmila Mykhailvna. Lady Death: The Memoirs of Stalin’s Sniper. Simon and Schuster, 2018.

- 30

Faeder, Eric. “‘Lady Death’ and The First Lady.” Home Of Franklin D Roosevelt National Historic Site (U.S. National Park Service), February 23, 2022. https://www.nps.gov/hofr/blogs/lady-death-and-the-first-lady.htm.

- 31

Pavlichenko, Lyudmila Mykhailvna. Lady Death: The Memoirs of Stalin’s Sniper. Simon and Schuster, 2018.

- 32

King, Gilbert. “Eleanor Roosevelt and the Soviet Sniper.” Smithsonian Magazine, February 21, 2013. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/eleanor-roosevelt-and-the-soviet-sniper-23585278/.

- 33

King, Gilbert. “Eleanor Roosevelt and the Soviet Sniper.” Smithsonian Magazine, February 21, 2013. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/eleanor-roosevelt-and-the-soviet-sniper-23585278/.

- 34

Pavlichenko, Lyudmila Mykhailvna. Lady Death: The Memoirs of Stalin’s Sniper. Simon and Schuster, 2018.

- 35

Tharoor, Ishaan. “Don’t Forget How the Soviet Union Saved the World from Hitler.” The Washington Post, May 9, 2015. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/worldviews/wp/2015/05/08/dont-forget-how-the-soviet-union-saved-the-world-from-hitler/.

- 36

Pavlichenko, Lyudmila Mykhailvna. Lady Death: The Memoirs of Stalin’s Sniper. Simon and Schuster, 2018.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)