The Ill-Fated Attempt to Build a Mother's Memorial in Washington

By the time she set out to build monuments, Daisy Breaux was a woman accustomed to getting what she wanted. An influential Washington hostess and amateur architect, she had built three of her own homes and flew in high circles. Once women won the vote in 1920, she decided that Washington was sorely missing a memorialization of women’s contributions to America. She dreamed up a Mothers’ Memorial: a fever dream of marble which blazed an equally bizarre trajectory through studios, society drawing rooms, and the D.C. courts.

Although she solicited three separate architects, raised thousands of dollars through two separate foundations, and had (allegedly) chosen a design, Breaux’s vision never became concrete. A scandalous court case ended with Breaux’s accusations of blackmail—by the monument’s own architect—dropped by a judge. Afterwards, Breaux seems to have lost interest, and the Mothers’ Memorial designs ended up in the wastebasket of history.

Margaret “Daisy” Breaux grew up in New Orleans high society and continued to fly in wealthy circles during her three marriages, in which she made it clear she was a force to be reckoned with. After her first marriage, she bulldozed the Charleston house gifted to her by her father-in-law to build a luxury hotel, which became known as “White House of the South” for its high-powered clientele.1 In 1918, she married Captain Clarence Calhoun, a Spanish-American War veteran and prominent Washington attorney. During this union, she designed a thirty-room Scottish castle to call home in Chevy Chase, Maryland.

It was with Calhoun that she attended the 1920 Democratic National Convention in California. Politicians there were eagerly appealing to the interests of the 26 million American women who had just gained suffrage.2 On the train home, Breaux reflected: “I came away from the Convention a thorough convert to [women’s] new place in the world, not only for equal rights in politics and business, but as a public speaker."3

On her return to Washington, Breaux created the Woman’s National Foundation to educate women about “their civil rights and duties as citizens.” She also began considering possibilities for a more visible reminder of women’s contributions to the nation. A WNF board member proposed a structure “in memory of the achievements of American women,” but only from “pioneer days to the present time.”4 Clarence Calhoun was willing to put up $1,000 for a pillar honoring his mother. A friend offered another donation to also include his mother’s name.

The WNF was short-lived. In a prelude to future organizational dysfunction, Breaux dissolved the Foundation as drama and jealousies engulfed the board. It was perhaps a bad sign for her current project that she considered these disagreements a uniquely feminine problem. “Many women,” she asserted. “Cannot bear to see one of their sisters, who has been on par with them, suddenly elevated to a position of authority over them.”5

Undeterred, Breaux rebranded and reorganized: the Women’s Universal Alliance would work expressly to build “an acropolis to the womanhood of all lands… and to the motherhood of the world.” 6 Now, she needed two things: money, and an architect.

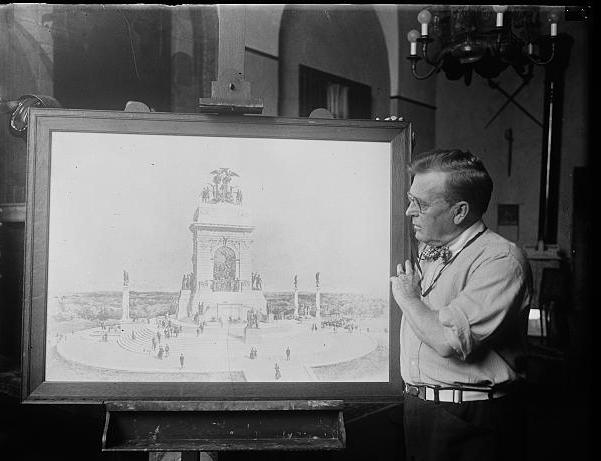

In 1924, a friend introduced her to William Clark Noble, one of America’s leading sculptors. For several years, Noble had toyed with ideas for a “Mothers of Men” memorial, and Breaux was interested in whether she could adapt his design to her needs.7 When Breaux arrived in his D.C. studio that summer, both believed they had found a partner to pursue their dreams.

The nature of Breaux and Noble’s partnership was later contested by both parties. Breaux claimed she had contracted Noble “only for purposes of illustration” and never expected to pay the sculptor, who turned out to be cantankerous and difficult to work with.8 Noble, conversely, maintained that Breaux and the WUA had approved his design, but Breaux’s domineering influence irreparably damaged both his model and its chances of becoming reality. Whatever the truth was, the artist and the organizer were at cross-purposes: one expected substantial compensation, and the other had little intention of paying it.

When work began in 1924, Noble did not press for a contract. Breaux “seemed like such a lovely lady” and there would be time to iron out details going forward.9 Besides, he had a lot of work to do.

The monument Noble envisioned was an imposing arch of white marble nearly 300 feet tall (the Lincoln Memorial is only 99 feet!), placed on a one-hundred-yard-long ziggurat of marble stairs. The arch would be filled in with a towering bas-relief showing mothers sending their sons to war and nursing wounded soldiers. Later features included four allegorical statues on columns surrounding the arch and a statuary scene on the roof. A representation of motherhood would have held a “Torch of Enlightenment” aloft in one hand, while offering another torch to figures of “Young Manhood” and “Young Womanhood.”10 Blocky, cumbersome, and incontestable, the monument’s silhouette would have dominated Washington’s skyline—which perhaps appealed to Noble and Breaux.

The WUA printed fundraising booklets with Noble’s design and solicited donations for its construction. Noble’s days were entirely devoted to perfecting the monument. Although Breaux later denied any intentions to use Noble’s work, it must have seemed to the sculptor as though she were entirely on board. In the year they worked together, Breaux only paid him $2,000, but constantly used Noble’s studio as a meeting place and showroom, entertaining wealthy potential donors.

She held fundraisers there well into the summer of 1925. At a gathering in May, international guests mingled and listened to addresses on women’s issues. A scale model of Noble’s monument sat on display, lit “from without and within” by tiny lightbulbs. Breaux stood before the audience of 150 people and described, with unquestionable candor, the model “as a temple of universal art” and a commemoration of “the services of great women and mothers.”11

Behind the scenes, the project was straining to its breaking point. Noble, not for lack of trying, was still without his contract, and he and Breaux disagreed vehemently on the design of the memorial. According to Breaux, Noble’s design was “so impractical” that a construction company “declined to compute” the cost of building it.12 She was willing to be “charitable” and help him to make the necessary “radical changes.”13

Those changes, according to Noble, amounted to Breaux completely reconstituting the memorial. She “changed her mind every other day” on the construction.14 Noble also blamed the skyrocketing costs on Breaux’s constant changes, which transformed his structure into “more of an office building than a true memorial.”15 All the while, he saw little in way of financial compensation.

In autumn of 1925, Noble reached his breaking point. Behind on rent for his studio and still without a contract, he wrote one final proposal for the WUA, outlining a perhaps unreasonable $500,000 payment for his contributions. When neither the WUA nor Breaux responded, Noble officially “withdrew” his design.16

As though it had been waiting for Noble’s resignation, the WUA announced a new affiliation with Joseph Geddes and a renewed fundraising drive for $15 million based on Geddes’ new design, which Breaux maintained did not “in the least” resemble Noble’s. The sculptor saw this as an utter betrayal—Geddes had been a subordinate of his on the project—and lamented: “They have ruined my life's work, destroyed my dearest dream, and now I am through.”17

For years, Noble stewed in resentment, persistently returning to the money Breaux owed him (a value he estimated between $30,000 to $300,000). According to Breaux, Noble’s representatives were bothersome and even threatened her reputation to secure the money, but she held firm. Noble had never been employed by the WUA; she owed him nothing.

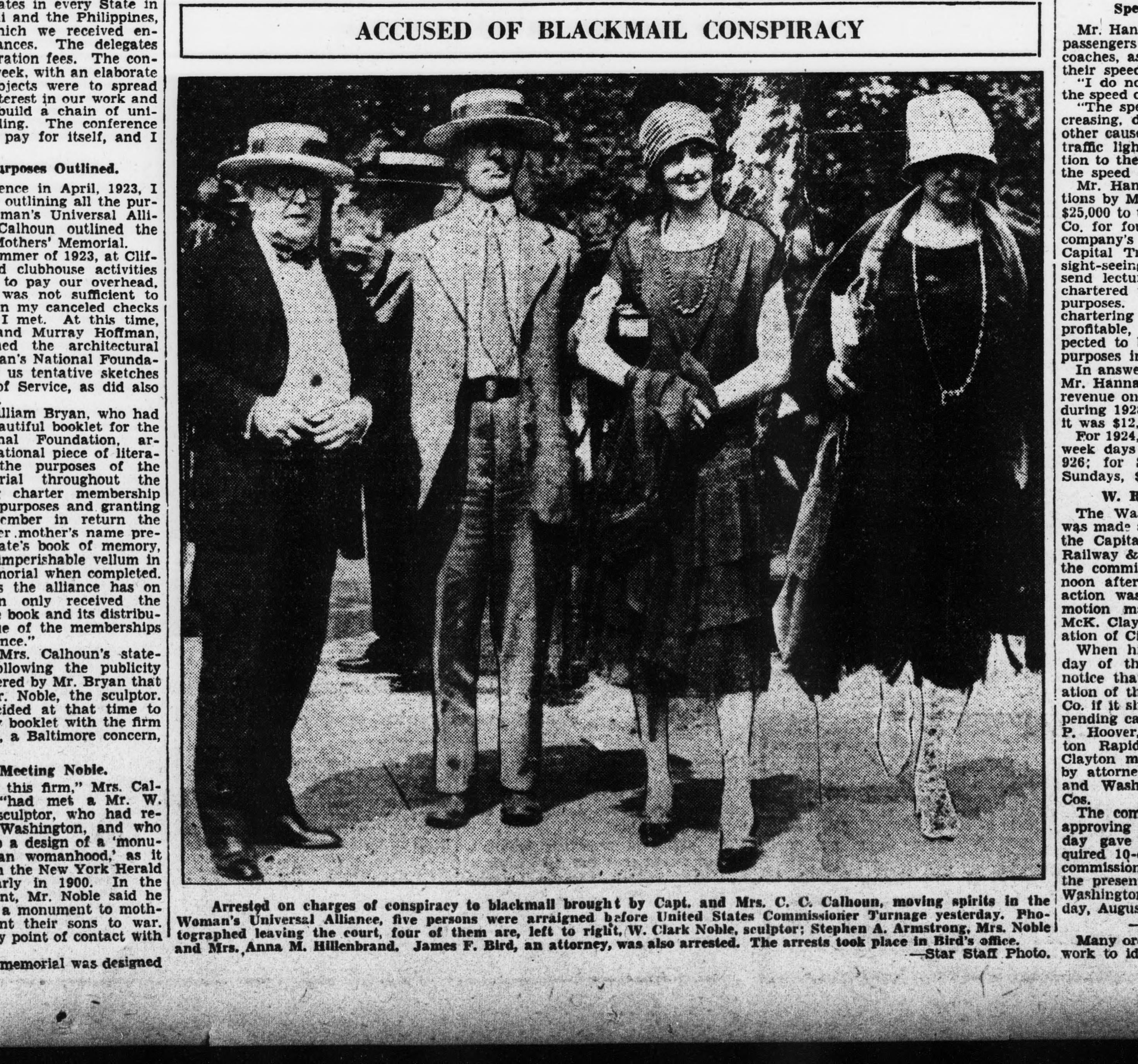

Finally, in August 1929, Breaux appeared to crack. Her husband, Clarence Calhoun, invited Noble, his wife Emilie, their lawyer James Bird, and two others to an office on Pennsylvania Avenue. Calhoun was willing to sign a check for $30,000 if Noble and the others agreed not to publish “charges derogatory to the character of the Calhouns.”18

What happened next is disputed. The Nobles signed the contract, but a disagreement arose between the other three, either over who should sign next or who would be the payee on the hefty check. The meeting ground to a halt.

At that point, Calhoun’s lawyer (actually a Department of Justice official) asked for his glasses: the secret signal to bring a team of deputy marshals crashing into the conference room to arrest the signatories. In the chaos, Breaux reportedly jumped up and down with glee, clapping her hands and shouting, “We caught you like mice in a trap!”19

Following the arrests, Breaux and Calhoun sued Noble and his co-defendants on charges of a $300,000 blackmail and extortion scheme. Noble’s lawyer and two accomplices had allegedly threatened to create a “rival organization” to “destroy” the WUA and publish “venomous” scandals about the Calhouns unless they agreed to pay up.20 To protect her reputation and finances, Breaux and her husband had organized the sting.

The defense maintained that Breaux never intended to pay Noble, nor did she truly mean to build any Mothers’ Memorial. Instead, she used the WNF and WUA as personal banks for projects like her castle in Chevy Chase (completed the year before on land ostensibly bought as a possible plot for the memorial). As Emilie Noble testified, “The only reason [Breaux] wanted a design [from Noble] was in order that money might be raised” for her own purposes.21

On the stand, Breaux condemned the “constant conspiracies and attacks” against her and her organization.22 To her credit, WNF members had received refunds when the organization folded, and the WUA’s accounting passed the scrutiny of at least one auditor. But the fact remained that after a decade of campaigning, the WUA had erected nothing but “4-by-5-foot pyramid topped by an American flag.”23

Both Breaux and Noble blamed the lack of progress on each other. Breaux insisted that Noble’s design had never been “satisfactory.”24 Noble recounted Breaux’s constant changes to the model and how she once demanded Noble replace a sculpture group with a fifty-foot statue of herself.

“I told her that was too much Calhoun,” he testified.25

Nonetheless, Breaux left the stand with her head high: “They’ve been trying to break me down for three days and they’ve failed,” she told reporters.26

Ultimately, the presiding judge threw the case out in June 1931 for lack of evidence. He did not award Noble back pay but cleared all five defendants of wrongdoing. Neither was Breaux ever charged with embezzlement: the accounting behind the WUA’s donations remained a mystery.

For the 73-year-old Noble, the excitement was almost too much. After the verdict was announced, he collapsed of a heart attack in the courtroom. The sculptor survived another seven years, but his career never fully recovered from his entanglement with Breaux.

Daisy Breaux, meanwhile, never got her Mothers’ Memorial off the ground. After the court case, her interest in the project seemed to fade. She promised to detail her plight against “the scoundrels and racketeers that infest Washington” in a second memoir. This book might have shed some light on the question, but it ended up as another incomplete venture.27

Perhaps it turned out for the best. The Mothers’ Memorial was an imperfect answer to a lack of female representation in Washington. It attempted to stand for all women but in fact represented only a small slice of historical American womanhood, excluding Native, unmarried, or childless women.

Washington’s modern monuments remain heavily skewed towards men. The Military Women’s Memorial in Arlington and the Vietnam Women’s Memorial are a start, and a 2020 bill cleared the Women’s Suffrage National Monument Foundation to begin surveying a site to commemorate American suffragettes.28 There is a long way to go, but one day soon a silhouette in Washington’s skyline could belong to women—just as Breaux and Noble envisioned in their frustrated dreams.

Footnotes

- 1

Mrs. Calhoun, Famed Social Leader, Dies. 1949. The Washington Post (1923-1954), Mar 22, 1949. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/mrs-calhoun-famed-social-leader-dies/docview/152183523/se-2 (accessed September 16, 2024).

- 2

Paranik, Amber. “‘Women Have the Vote!’” The Library of Congress, November 3, 2020. https://blogs.loc.gov/headlinesandheroes/2020/11/women-have-the-vote/.

- 3

Kelly, John. “A Mom-Umental Failure.” Washington Post Magazine, May 11, 2008. https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/story/2008/05/09/ST2008050901253.html?sid=ST2008050901253&itid=lk_interstitial_manual_18.

- 4

Kelly, John.

- 5

Breaux, Daisy. The Autobiography of a Chameleon. Potomac Press, 1930. p.310 https://archive.org/details/bwb_P8-CYZ-300/page/404/mode/2up.

- 6

Kelly, John.

- 7

“Defense Attacks, Calhoun Charges.” Evening star. [volume] (Washington, D.C.), 11 May 1931. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1931-05-11/ed-1/seq-17/>

- 8

“Nobles Had Signed Calhoun Contract, US Agent Avers.” Evening star. [volume] (Washington, D.C.), 08 Aug. 1929. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1929-08-08/ed-1/seq-1/>

- 9

Kelly, John.

- 10

Kelly, John.

- 11

“Society.” Evening star. [volume] (Washington, D.C.), 09 May 1925. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1925-05-09/ed-1/seq-8/>

- 12

“Nobles Had Signed Calhoun Contract, US Agent Avers.” Evening star. [volume] (Washington, D.C.), 08 Aug. 1929. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1929-08-08/ed-1/seq-1/>

- 13

“Blackmail Trial Marked by Clash Over Memorial.” Evening star. [volume] (Washington, D.C.), 13 May 1931. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1931-05-13/ed-1/seq-17/>

- 14

“Mrs. Calhoun Threatened Noble, His Wife Testifies.” Evening star. [volume] (Washington, D.C.), 25 May 1931. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1931-05-25/ed-1/seq-17/>

- 15

“Noble Files Suit for Accounting in Memorial Project.” Evening star. [volume] (Washington, D.C.), 19 Feb. 1930. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1930-02-19/ed-1/seq-2/>

- 16

“Nobles Had Signed Calhoun Contract, US Agent Avers.” Evening star. [volume] (Washington, D.C.), 08 Aug. 1929. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1929-08-08/ed-1/seq-1/>

- 17

Kelly, John.

- 18

Kelly, John.

- 19

Kelly, John.

- 20

“Five Face Charges of Blackmail Plot Against Calhouns.” Evening star. [volume] (Washington, D.C.), 07 Aug. 1929. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1929-08-07/ed-1/seq-2/>

- 21

“Memorial Called Financial Venture.” Evening star. [volume] (Washington, D.C.), 26 May 1931. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1931-05-26/ed-1/seq-17/>

- 22

“Nobles Had Signed Calhoun Contract, US Agent Avers.” Evening star. [volume] (Washington, D.C.), 08 Aug. 1929. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1929-08-08/ed-1/seq-1/>

- 23

Kelly, John.

- 24

“Blackmail Trial Marked by Clash Over Memorial.” Evening star. [volume] (Washington, D.C.), 13 May 1931. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1931-05-13/ed-1/seq-17/>

- 25

Kelly, John.

- 26

“Mistrial is Seen in Calhoun Case; Plea Withdrawn.” Evening star. [volume] (Washington, D.C.), 12 May 1931. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1931-05-12/ed-1/seq-17/>

- 27

Jones, Mark. “The Irrepressible Daisy Breaux.” MarkJonesBooks, January 15, 2016. https://mark-jones-books.com/2016/01/14/the-irrepressible-daisy-breaux/.

- 28

Women’s Suffrage National Monument Foundation. “About — Women’s Suffrage National Monument Foundation.” Women’s Suffrage National Monument Foundation. Accessed September 19, 2024. https://www.womensmonument.org/about.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)