From Hiroshima to Washington: A Beloved Bonsai's Journey from War to Peace

On March 8, 2001, two men flew into Dulles International Airport from Japan. You’d think jet lag and exhaustion would keep them bed-ridden, but immediately after checking into their hotel, the men bolted for the United States National Arboretum. Twenty-one-year-old Shigeru Yamaki and his twenty-year-old brother Akira were anything but ordinary visitors. They were the grandsons of Masaru Yamaki, a highly respected practitioner of the art of bonsai,1 the Japanese art of miniaturizing trees through horticultural techniques that were refined from China’s art of penjing around the 7th or 8th century AD.2 The brothers didn’t fly halfway around the world just to admire the Arboretum’s acclaimed collection of plants and trees from around the world; they were here to find one tree in particular.

Shigeru and Akira entered the National Bonsai & Penjing Museum on the Arboretum’s grounds and approached a Japanese-speaking volunteer. They asked for directions to a bonsai that their grandfather had donated to the museum in 1976. Warren Hill, the curator of the museum, was alerted that family of the tree’s original owner were here to see the Yamaki pine.

Hill greeted the Yamaki brothers, and led them to the tree they had flown thousands of miles to see in person. It was a Japanese white pine, just two feet tall, with a stout trunk and spindly greenish-yellow needles. Shigeru and Akira recognized it immediately from stories and photos their family had shared with them their entire lives.

As the brothers bowed in respect, Hill had little idea of the importance this tree played not just to the brothers or the Arboretum, but to Washington, D.C. itself. All Hill and the Arboretum knew about this tree was that it was 375 years old, and that Japan officially donated the bonsai to the United States as a gift for the American Bicentennial 25 years earlier.

Hill invited the brothers out to lunch, along with two Japanese volunteers from the museum. Through the volunteers’ translation, Shigeru and Akira began to tell Hill the real story of the Yamaki pine. It was the secret story of one of D.C.’s strongest yet most subtle symbols of peace and remembrance.

Fifty-six years earlier and seven thousand miles away, Masaru Yamaki was home with his family at a quarter-past eight in the morning when a tremendous force blasted through his house. The ceiling collapsed and the windows blew out, sending shards of glass slicing across his skin. It was August 6, 1945. Two miles away,3 the first atomic bomb used in warfare had just detonated 2,000 feet above the city of Hiroshima in Japan. The bomb wiped out 90% of the city, killing 80,000 Japanese in an instant. An estimated 60,000 more would die by the year’s end.4

Masaru Yamaki was lucky. He and his family survived the blast with glass stuck in their skin, but no more serious injuries. That wasn’t all. The Yamakis operated an outdoor plant nursery on their family compound, and not a single plant was touched. The perimeter wall was miraculously left standing after a blast that leveled every structure just a mile closer to the explosion’s epicenter. One tree in particular was extraordinary. The Yamakis had kept it in their care for at least five generations, since one of their ancestors collected it from a Hiroshima Bay island in 1625. It was painstakingly trained in the art of bonsai over the next 400 years.5

After the Yamakis' story was shared, Hill and everyone else at the Arboretum were stunned. “It just completely blew our minds,” said Felix Laughlin, president of the National Bonsai Foundation. “We knew nothing about that.”6 They understood that the Yamaki pine wasn’t just an artistic masterpiece, it was a historical artifact, and a living testament of peace and reconciliation.

Flash forward to 1972, and America was anticipating the country’s bicentennial in 1976. Leaders of institutions across the government were developing plans to celebrate the country’s 200th birthday, and Director John Creech of the United States National Arboretum had a novel idea. Dr. Creech was a passionate fan of bonsai. As countries were offering gifts to the U.S. to celebrate her birthday, Creech knew he wanted something from Japan that could become as beloved and everlasting as Tokyo’s gift of cherry blossoms to D.C. in 1912.

In August 1973, Dr. Creech reached out to his old plant collecting buddies in Japan,7 who were members of the Nippon Bonsai Association, Japan’s official organization for the practice of bonsai. He asked the Association’s directors for a generous gift of bonsai trees to the National Arboretum. In September 1974, Dr. Creech flew to Japan to hash out the details of his plan with the directors and make his formal request.8

“The main reason he got this to happen was the fact that he was a very delightful person to be around,” said Bob Drechsler, who became the first curator of the National Bonsai & Penjing Museum in 1976. “He’s one of these people that walked into the room and filled the room.”9 After a little reluctance and some assurance from a friend in the Association, Dr. Creech convinced the directors that the bonsai would be in safe hands. The directors promised Creech they would do their best to get him his trees.

On March 6, 1975, bonsai began arriving at the Nippon Bonsai Association in Tokyo from all over Japan. The bonsai were hand-selected by the Association’s directors in confidence that these were the greatest masterpieces of the art form. About half of them came from private owners like Masaru Yamaki, who was also a member of the Association, and had helped to revitalize bonsai as a commercial enterprise after World War II.10

The trees were carefully repotted, pruned and plucked into impeccable shape to get them ready for their hand-off. On March 20, Japanese and American dignitaries gathered in a Tokyo hotel for a presentation ceremony to give the bonsai a heartfelt goodbye. The president of the Bonsai Association congratulated the U.S. for the Bicentennial and handed a document that officiated America’s ownership of the bonsai to James Hodgson, U.S. Ambassador to Japan. Hodgson formally accepted the bonsai on behalf of the United States and expressed deep gratitude to Japan for thirty years of peace and friendship in the postwar world.11

“They were still recovering from the war, for sure,” said Felix Laughlin. “It was something that was so important, I think to them, to tell the American people ‘we forgive you for the bombing of Hiroshima. We’re sorry for the war.’ It said a lot, and the Yamaki pine really represents the essence of how the Japanese felt about the gift.”12

Dr. Peter Kuznick is a history professor and the director of the Nuclear Studies Institute at American University in Washington, D.C. “The fact that it came from the people of Japan to the people of the United States was almost a way to bypass tension between the governments during this time. Because it was the people of Japan who fought the people of the United States during the war. (It) represented something symbolically significant at the time, a gesture of friendship, a gesture of peace, a gesture of building the kind of ties that allow for a different kind of economic and political relations, and easing of tensions.”13

Dr. Creech expected the Nippon Bonsai Association to donate just a few trees, but it collected fifty, one for each American state. World War II’s Emperor Hirohito decided to contribute three more trees from his Imperial Household, including a 180-year-old red pine, his personal favorite. Altogether, fifty-three bonsai were assembled into a collection priced at $4 million. Between March 21 and 26, 1975, the bonsai were publicly exhibited in Tokyo’s Ueno Park for the Japanese people to get one last glimpse of the trees before their departure.14

On March 31, Dr. Creech and the Association’s directors watched carefully as the bonsai were packed up into crates and loaded onto trucks. The directors waved farewell as the last truck took off for the airport. Dr. Creech never let the bonsai out of his sight throughout the Pan-American flights from Tokyo to San Francisco and then on to Washington, D.C.15

The Yamaki pine and its travel buddies spent a year in quarantine in Glenn Dale, Maryland under the care of the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Bob Drechsler was given the responsibility of caring for the Japanese bonsai and inspecting them for any signs of disease that could spread to other trees. Drechsler would later be called “Bonsai Bob” for his care of the Arboretum’s Japanese collection. He routinely cared for the Yamaki pine for years while knowing nothing of its true history.16

In 1976, America’s 200th anniversary was commemorated through parades, festivals and reenactments across the country. An international fleet of warships sailed past New York and Boston. The American Freedom Train toured the nation.17 Washington, D.C. was the life of the party, with the opening of the National Air and Space Museum right next door to a twelve-week festival of American folklife on the National Mall.18 The gifts kept on coming. The UK loaned one of the four surviving copies of the Magna Carta to the Capitol.19 Other nations donated paintings, sculptures, and commemorative photo essays, among other gifts.20

On the evening of July 9, 1976, some of America’s and Japan’s highest dignitaries gathered at the U.S. National Arboretum to celebrate Japan’s gift and dedicate The National Bonsai Collection. Ambassador Hodgson attended alongside U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger and Japan’s Prime Minister Nobusuke Kishi.21 A Marine band played before Dr. John Creech delivered opening remarks, followed by speeches by the director of the Nippon Bonsai Association, America’s Secretary of Agriculture, the Ambassador of Japan, and finally Henry Kissinger. He said that Japan’s gift represented the “care, thought, attention and long life we expect our two peoples to have.”22 The Washington Toho Koto Society serenaded the after-party with Japanese music as attendants strolled past the Arboretum’s new bonsai garden.23

Thus began the National Bonsai & Penjing Museum. The newly constructed Japanese Pavilion and bonsai garden opened to the public a day after the ceremony. If you visited the garden after opening day on July 10, 1976, you would have strolled along a cobblestone path through a dark forest of Japanese cryptomeria trees, crossed a bridge over a koi pond, before turning right towards the Japanese Pavilion. Finally, you would have seen one of the world’s most historic bonsai resting modestly against a wooden fence.24 Most of this layout has survived until the present day, albeit with an extensive renovation in 2017 that shed new light on the museum and the Yamaki pine.

In 1986, Dr. Creech celebrated the ten-year anniversary of the museum’s founding with the opening of a Chinese Pavilion to house a gift of penjing trees that China gifted to the United States after Nixon’s historic visit in 1972. The museum has accepted several donations of bonsai and penjing since 1976. A North American Pavilion was added to recognize the growing popularity of bonsai in North America and houses the greatest collection of bonsai cultivated by American masters.

Today, the National Bonsai & Penjing Museum boasts the greatest collection of bonsai trees outside Japan. It houses 300 bonsai and penjing that frequently rotate on and off-exhibit and has a sister museum in Japan. The Bicentennial gift sparked interest in bonsai throughout the international community. Bonsai have become links across generations and nations.25

The Yamaki pine may have survived the passage of centuries and nuclear war, but its continued survival is anything but assured. Jack Sustic has been curator of the National Bonsai & Penjing Museum and the Yamaki pine’s primary caretaker since 2002. The pine is watered daily, checked for bugs, rotated towards the sun twice a week, and repotted every three to five years.26 Sometimes, Sustic is kept up at night by thoughts of the Yamaki pine’s longevity. After all, Japanese white pines are supposed to live no more than 200 years.

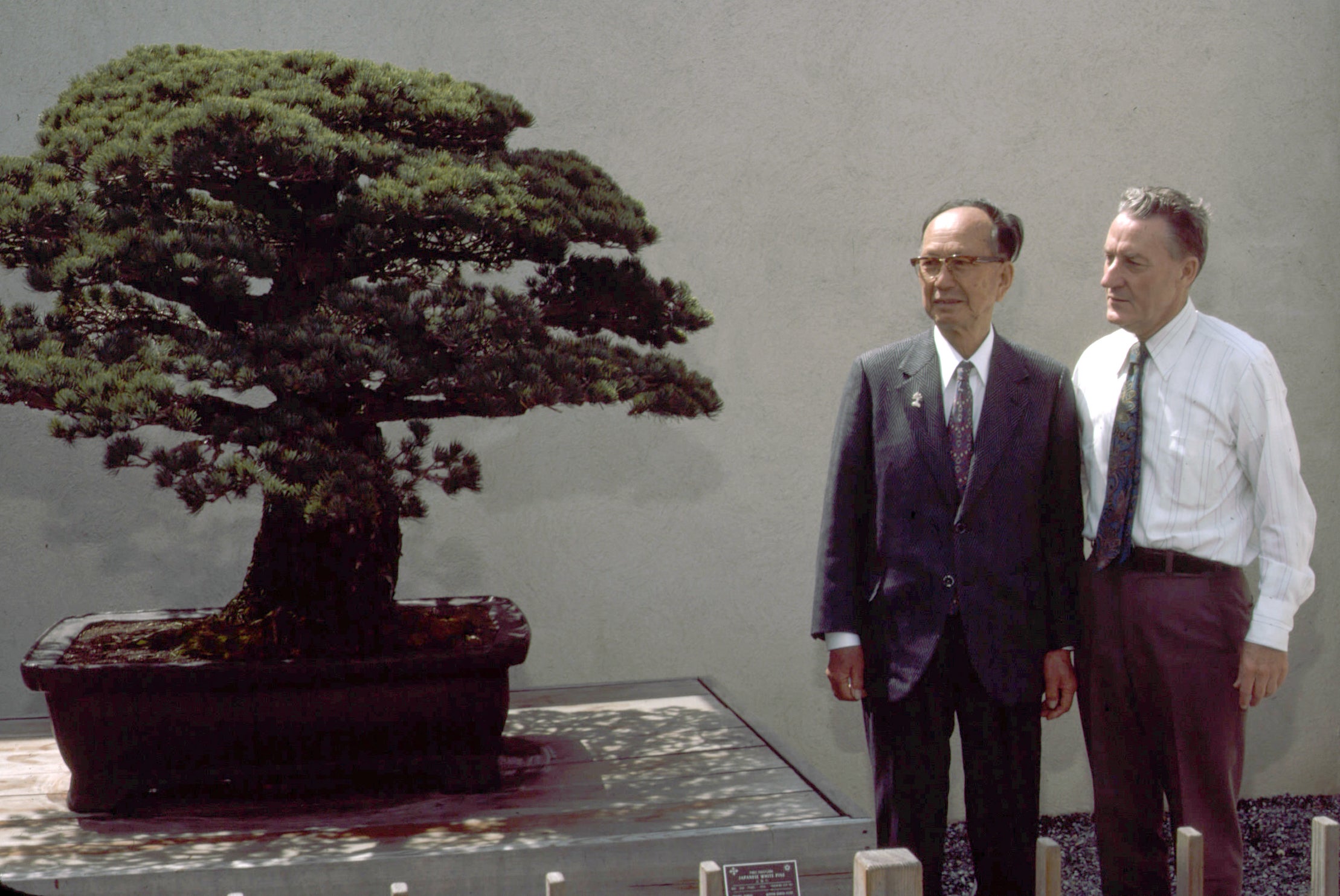

“I find it amazing that Masaru Yamaki could give a priceless bonsai basically to his enemy and not say a word about it,” said Felix Laughlin. “I get emotional just talking about it.”27 If Masaru Yamaki held any animosity towards the country that almost killed him, he didn’t show it. He actually visited the Arboretum in 1979 to see the pine, accompanied by Dr. Creech. Apparently, he never told Creech about the tree’s survival in Hiroshima. Masaru passed away at the age of 89. Members of the Yamaki family have returned multiple times to the Arboretum since rediscovering their family treasure, including Masaru’s daughter in 2003.28

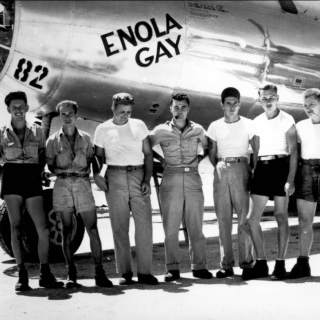

It’s perhaps bitterly ironic that the Yamaki pine lives thirty-seven miles away from the Enola Gay, the American B-29 bomber that dropped the “Little Boy” on Hiroshima, where the plane rests at the National Air and Space Museum’s annex at Dulles International Airport.29

In a city defined by the eternal combat of power and politics, the Yamaki pine survives as one of Washington D.C.’s most enduring reminders that bridges can be built even between mortal enemies, and that the grandest gestures of peace can often be the most subtle. Sometimes, they can live silently among us.

Footnotes

- 1

National Bonsai Foundation. “The Yamaki Pine: Over 400 Years of History,” 2003. https://www.bonsai-nbf.org/yamaki-pine.

- 2

Robert J. Baran. “History of Bonsai.” Bonsai Empire, n.d. https://www.bonsaiempire.com/origin/bonsai-history.

- 3

National Bonsai Foundation. “The Yamaki Pine: Over 400 Years of History,” 2003. https://www.bonsai-nbf.org/yamaki-pine.

- 4

The International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN). “Hiroshima and Nagasaki Bombings,” n.d. https://www.icanw.org/hiroshima_and_nagasaki_bombings.

- 5

National Bonsai Foundation. “The Yamaki Pine: Over 400 Years of History,” 2003. https://www.bonsai-nbf.org/yamaki-pine.

- 6

MPT Presents | Bicentennial Bonsai: Emissaries of Peace. Documentary. PBS, 2024. https://www.pbs.org/video/bicentennial-bonsai-emissaries-of-peace-r4ckni/.

- 7

MPT Presents | Bicentennial Bonsai: Emissaries of Peace. Documentary. PBS, 2024. https://www.pbs.org/video/bicentennial-bonsai-emissaries-of-peace-r4ckni/.

- 8

Bonsai Fly to USA: A Gift in Honor of the American Bicentennial (Documentary). Documentary. The National Bonsai Foundation, 1975. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-5AzWPrf5gI.

- 9

MPT Presents | Bicentennial Bonsai: Emissaries of Peace. Documentary. PBS, 2024. https://www.pbs.org/video/bicentennial-bonsai-emissaries-of-peace-r4ckni/.

- 10

National Bonsai Foundation. “The Yamaki Pine: Over 400 Years of History,” 2003. https://www.bonsai-nbf.org/yamaki-pine.

- 11

Bonsai Fly to USA: A Gift in Honor of the American Bicentennial (Documentary). Documentary. The National Bonsai Foundation, 1975. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-5AzWPrf5gI.

- 12

MPT Presents | Bicentennial Bonsai: Emissaries of Peace. Documentary. PBS, 2024. https://www.pbs.org/video/bicentennial-bonsai-emissaries-of-peace-r4ckni/.

- 13

MPT Presents | Bicentennial Bonsai: Emissaries of Peace. Documentary. PBS, 2024. https://www.pbs.org/video/bicentennial-bonsai-emissaries-of-peace-r4ckni/.

- 14

Bonsai Fly to USA: A Gift in Honor of the American Bicentennial (Documentary). Documentary. The National Bonsai Foundation, 1975. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-5AzWPrf5gI.

- 15

MPT Presents | Bicentennial Bonsai: Emissaries of Peace. Documentary. PBS, 2024. https://www.pbs.org/video/bicentennial-bonsai-emissaries-of-peace-r4ckni/.

- 16

The National Bonsai & Penjing Museum. “The Museum,” n.d. https://www.bonsai-nbf.org/bonsai-museum.

- 17

Larry Wines. “The Story of the 1975 - 1976 American Freedom Train.” The Story of America’s Freedom Trains, 1998. https://www.freedomtrain.org/american-freedom-train-home.htm.

- 18

Smithsonian Institution. “1976 Bicentennial of American Independence,” n.d. https://www.si.edu/spotlight/united-states-bicentennial.

- 19

Architect of the Capitol. “Magna Carta Replica and Display,” n.d. https://www.aoc.gov/explore-capitol-campus/art/magna-carta-replica-and-display.

- 20

Special, Linda Charleton. “Spain Lends 8 Goyas for Bicentennial.” The New York Times, April 22, 1976, sec. Archives. https://www.nytimes.com/1976/04/22/archives/spain-lends-8-goyas-for-bicentennial-spain-lends-8-goyas-for.html.

- 21

MPT Presents | Bicentennial Bonsai: Emissaries of Peace. Documentary. PBS, 2024. https://www.pbs.org/video/bicentennial-bonsai-emissaries-of-peace-r4ckni/.

- 22

Katie Nodjimbaden. “The Bonsai Tree That Survived the Bombing of Hiroshima,” August 4, 2015. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/390-year-old-tree-survived-bombing-hiroshima-180956157/.

- 23

MPT Presents | Bicentennial Bonsai: Emissaries of Peace. Documentary. PBS, 2024. https://www.pbs.org/video/bicentennial-bonsai-emissaries-of-peace-r4ckni/.

- 24

Prima, Lee Lorick. “A Bicentennial Gift of Bonsai To the People of America From the Japanese.” The New York Times, July 4, 1976, sec. Archives. https://www.nytimes.com/1976/07/04/archives/a-bicentennial-gift-of-bonsai-to-the-people-of-america-from-the.html.

- 25

The National Bonsai & Penjing Museum. “The Museum,” n.d. https://www.bonsai-nbf.org/bonsai-museum.

- 26

Margaret Sessa-Hawkins. “Centuries-Old Bonsai That Survived Atomic Bomb Gets Honored 70 Years Later.” PBS News, August 3, 2015. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/nation/centuries-old-bonsai-that-survived-atomic-bomb-gets-honored-70-years-later.

- 27

Siddiqui, Faiz. “This 390-Year-Old Bonsai Tree Survived an Atomic Bomb, and No One Knew until 2001.” The Washington Post, August 3, 2015. https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/the-390-year-old-tree-that-survived-an-atomic-bomb/2015/08/02/3f824dae-3945-11e5-8e98-115a3cf7d7ae_story.html.

- 28

National Bonsai Foundation. “The Yamaki Pine: Over 400 Years of History,” 2003. https://www.bonsai-nbf.org/yamaki-pine.

- 29

Wright, Jennifer. “Exhibiting the Enola Gay.” Smithsonian Institution Archives, June 25, 2020. https://siarchives.si.edu/blog/exhibiting-enola-gay.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)